Thriving Together

Salish and Kootenai youth unify amid challenges

Story by Hannah Staus. Photos by Maddie McCuddy.

It was a Saturday morning earlier this year when 20-year-old Jet DuMontier stood in the vegetable aisle of a Walmart store on the Flathead Indian Reservation. DuMontier was wearing their black cargo pants and a gray hoodie. Their partner had just moved into a new apartment and needed to buy basic groceries to start a new chapter of their life. DuMontier enjoyed watching the people surrounding them, while their partner debated what to buy.

Enlarge

Then a teenage boy lifted his shirt toward DuMontier to show the gun on his hip.

“It was very intentional because he didn’t have his shirt up the first time I saw him,” DuMontier said. “I’m sure he was reacting to us.”

DuMontier and their partner were both born biologically female and both identify as nonbinary and use they/them pronouns. They were affectionate in the supermarket. That’s how DuMontier assumed the boy recognized them as a queer couple.

Concentrating on their shopping list, their partner hadn’t seen the gun. But DuMontier became quiet. As a queer person, all the alarm bells were ringing for DuMontier.

“I felt so unsafe,” DuMontier remembered. “The second I saw that, all this horrible shit just started going through my head. A fucking Walmart shooting.”

DuMontier’s thoughts ran wild. They went through all the possible scenarios of what could happen next. How could DuMontier save them from the situation? They only knew of one nearby entrance and exit. DuMontier thought of all possible escape routes while they pushed their partner into the next aisle – away from the gun.

It didn’t come to a shooting that Saturday. The boy’s mother told him to put his shirt back down.

“He didn’t look a day older than 17,” DuMontier recalls.

But even though there was no violence that day and no physical signs of racism or queer hostility were left behind, psychological scars remain. DuMontier is now more mindful of where and when they show affection to their partner in public. They don’t feel safe on their reservation anymore.

Election results of young voters

Nearly half of young voters across the nation, dubbed Gen Z in popular media, voted for Donald Trump in 2024, a significant increase from his previous presidential bid. About 47% cast votes for the Republican candidate last year while about 36% did the same in 2020.

At the beginning of March 2025, there were 2,108 enrolled citizensof the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes aged 23 and younger, according to Robert McDonald, the tribes’ spokesperson.

Like most of Montana, the polling places located in the major towns on the Flathead reservation supported Trump, including St. Ignatius and Ronan. Voters in Arlee supported the Democratic candidate, Kamala Harris, according to results posted by the Montana Secretary of State’s office.

However, since the election, young people have swayed. Many have grown more disillusioned and concerned with the economy, its environmental policies, and the overall treatment of diverse communities. Like DuMontier, some feel targeted by policies of the current administration as their rights to climate mitigation, education, and diversity are under attack.

In fact, the Institute of Politics at the Harvard Kennedy School released a report in April showing that only about 15% of young people believe the country is moving in the right direction and less than one-third approve of Trump’s performance.

The worries that young people have are as diverse as the young people themselves. Many mentioned that their main concerns are: school closures, growing racism and the fact that tribal resources, as well as natural resources, are being stolen. But in the face of mass layoffs and an uncertain economy, young people are now also worried about future job security, especially in nature conservation, which is important to the CSKT tribes.

Nevertheless as often in difficult times, this burden also sparks motivation in some to try even harder.

Top: Jet DuMontier leads a game of dictionary charades at a Spirit of Many Colors meeting. DuMontier and their sister, Chula, came up with the game as kids. The siblings hope the club can be a safe place for anyone on campus, not just the queer community. Bottom: Gracie Bell Reed gets on the bus that brings her home from Two River Eagle School. Reed, a senior, recently transferred from Billings to Pablo when her mom started pursuing a nursing degree.

Queer youth under attack

“I have the feeling that people have become bolder since the election,” said DuMontier, a Salish-Kootenai and Mexican descendant. “Hate is coming to the surface more now than it was before. It is such a scary feeling. I don’t ever want to feel scared to hold my partner’s hand, just because we are visibly queer.”

Being a young, queer person is becoming more and more difficult with new orders being made every other week that directly impact queer people’s lives. Executive orders by President Donald Trump, such as recognizing only two genders defined at birth and withdrawing support for gender-affirming care for transgender youth, directly affect youth throughout the U.S. Especially American Indian and Alaska Native youth, who are also often affected by racism.

“I’ve really taken a step back from going out and going to town, because of that aspect of safety,” DuMontier said. They are a Tribal Historic Preservation student at the Salish Kootenai College where they are also part of the Spirit of Many Colors club, a student initiative and safe space for the queer community on campus.

Jet and their sibling Chula DuMontier were part of a group of high schoolers at Two Eagle River School that started the Two-Spirit beading group Nk̓ʷuwilš. Translated to English, the group is called ‘Coming together as one’ and it is a youth-led safe space for Two-Spirit and Native LGTBQ+ people to build community.

Supporting each other in community

Sheldon Clairmont is the Community Engagement and Youth Programing Coordinator of the Montana Two Spirit Society.

According to him, Two-Spirit is a contemporary pan-Indigenous term used by some Indigenous tribes to describe Native people who fulfill a traditional third-gender or gender-variant social role within their communities, often encompassing both masculine and feminine traits. Within their tribes, two-spirit people often fill spiritual, ceremonial and leadership roles, and are considered sacred. To some Two-Spirit people, this term also describes people who are gay and lesbian as well.

Being Bitterroot-Salish himself, Clairmont is a point of contact for Two-Spirit youth and has noticed how the new government has affected their sense of security.

“But I also think in other ways, this is not really anything new for us as Indigenous people,” Clairmont said. “Our lives and well-being are in flux, like everyone else is just feeling it right now, this is what we’ve been dealing with for centuries.”

Jet and Chula DuMontier both went to the Two Eagle River School in Pablo. The school is often a safe harbor for all the children who struggled at public high schools. Tribal parents founded it in 1974 as an alternative school for Indigenous students who did not succeed in traditional public schools. The Flathead tribes run the school, but it is federally funded as a Bureau of Indian Education contract school.

In the high school, the DuMontier siblings joined a student-led queer club, formerly called the Fruit Bowl Club. The club still exists, but its members choose not to go public with it anymore out of safety concerns.

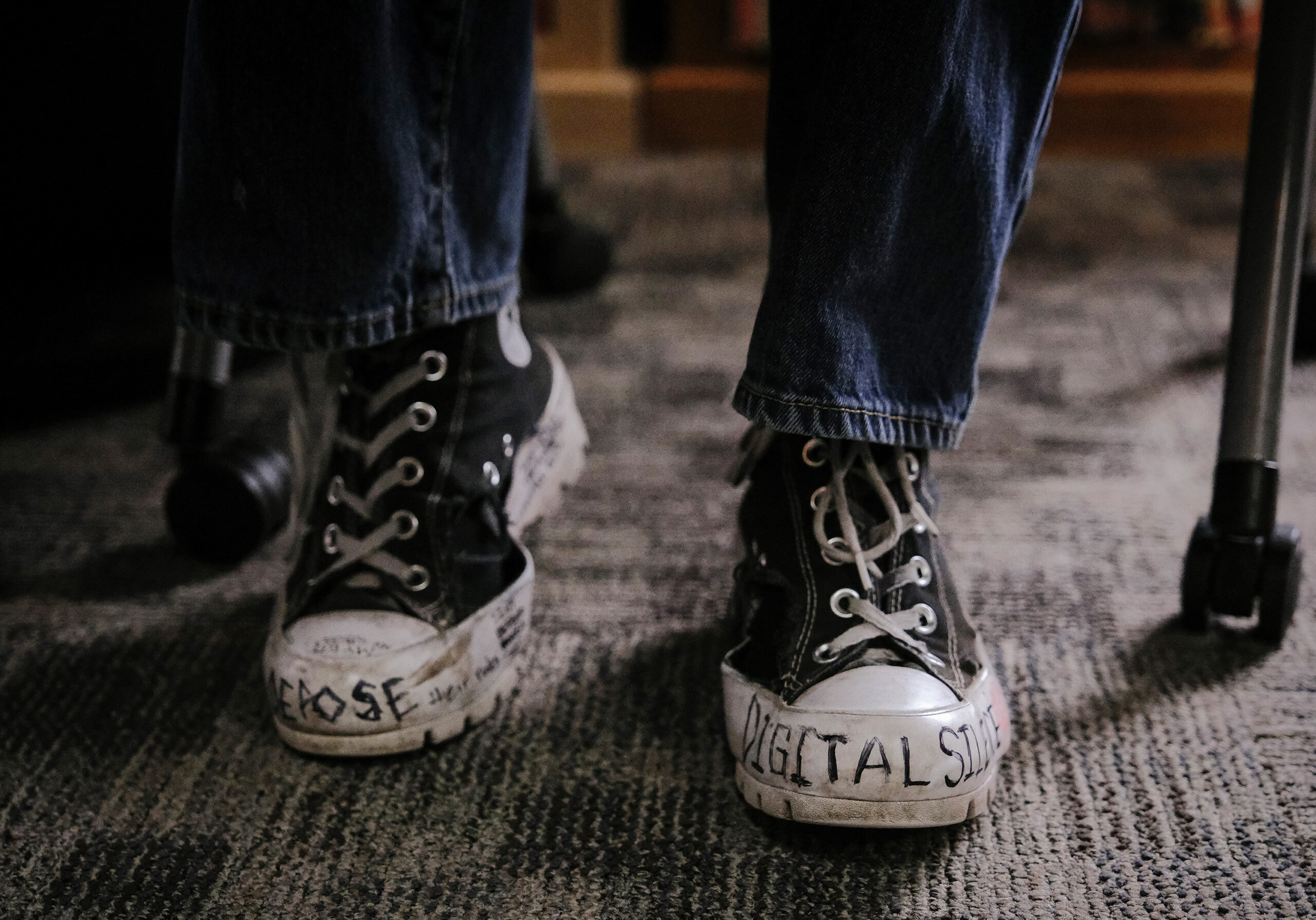

“We can’t really exist in our current government,” Josey Usher said while she played with the laces of her Converse shoes. The 15-year-old with dark eye makeup and red-brown hair had written “Deny, Defend, Depose” and “Kamala Harris 2028” in Sharpie on them. She joined the high school queer club when she moved from homeschooling to the Two Eagle River School.

Usher noticed that most of the members look for safety in their club, especially if they have a home that doesn’t support them, but also safety from the government. Being bisexual herself, she says she is comparatively okay.

“Every day I wake up and I’m like, we’re gonna get through the day. No matter what happens with our politics, you’re going to get through it eventually,” Usher said. But she said she has many friends who are suffering.

“I don’t worry just about my friends. I worry about my mom. That’s why I always go into town with her,” Usher said.

She hopes to become a Democratic politician and campaign for the rights of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Until then, she is working for the school newsletter to get her voice heard.

Making their voice heard

The video school newsletter “Inside the Nest” was born when the high school students were supposed to archive old newsletter episodes for the 50-year jubilee of the Two Eagle River School. This inspired the youth to do their own reporting and publish clips on Facebook.

Gracie Bell joined the newsletter when she transferred from Billings to Pablo. The 17-year-old with long brown hair was sitting at the kitchen table with her mother Holly Reed. Both were wearing colorful shirts with a Native American design. Their aunt designed them.

The whole family moved from Billings to Pablo and now lives in student housing because Reed started studying Nursing at Salish Kootenai College.

Ever since Bell joined a democracy event with her old high school, she has been deeply interested in politics. As the political editor, she informs her peers mostly about politics that affect the reservation.

“I try to keep up with the 2025 American Indian Caucus in Helena. I think it is pretty awesome that they have local people in the caucus that know the struggle of living on the reservations,” she said.

But she often has the feeling that her classmates don’t really know what is going on in politics.

“I just feel like not only does it have an effect on my life, but it has an effect on everybody’s life, especially being Native and Crow,” Bell said.

She pointed out that the Department of Education is facing massive budget cuts as well as the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which was forced to close offices throughout the country, including two in Montana. “That puts a lot of reservation schools at risk that don’t really have the funding.”

The policy has already had a very real impact on Bell’s life. She originally wanted to join the Marines after high school and then study medicine at Harvard.

But Bell has abandoned her big plans. She still wants to go to the military but after that, she only wants to apply to colleges in Montana, Washington, and Oregon.

“I just don’t want to go somewhere where there is stuff like the whole immigration and customs enforcement situation and the CIB (Certificate of Indian Blood) and tribal identification thing, I don’t want anything like that happening to me at all,” Bell said. “I think just living in bigger cities does scare me.”

Despite the challenges that these changes bring, her interest in politics and her involvement in the school newsletter shows that Bell no longer wants to be a bystander. After the “Inside the Nest” project ends, she wants to continue her work and start her own social media blog to inform her friends.

Informing tribal members and beyond

Sam Sandoval, editor of the tribal newspaper Char-Koosta News, encourages youth like Gracie Bell to go into journalism. He sees the responsibility of journalists to inform the tribal citizens and beyond about what is going on in the tribal world, politically but also socially.

“I think our newspaper was one of the very few at the beginning of the MMIW crises to talk about that,” Sandoval said, referring to the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women epidemic.

Stories like that have power beyond the borders of the reservation. Char-Koosta News has already made it into the national news several times.

Top: Gracie Bell laughs with her sister, Brittny Reed, on their bus ride home. Bell and Reed are from the Crow reservation, and recently moved to the Flathead reservation. Bottom: Gracie Bell and her sister Brittny Reed walk to their home on the campus at Salish Kootenai College. They live in student housing with their mom, Holly Reed, who is studying nursing at the college.

School closings are the main concern

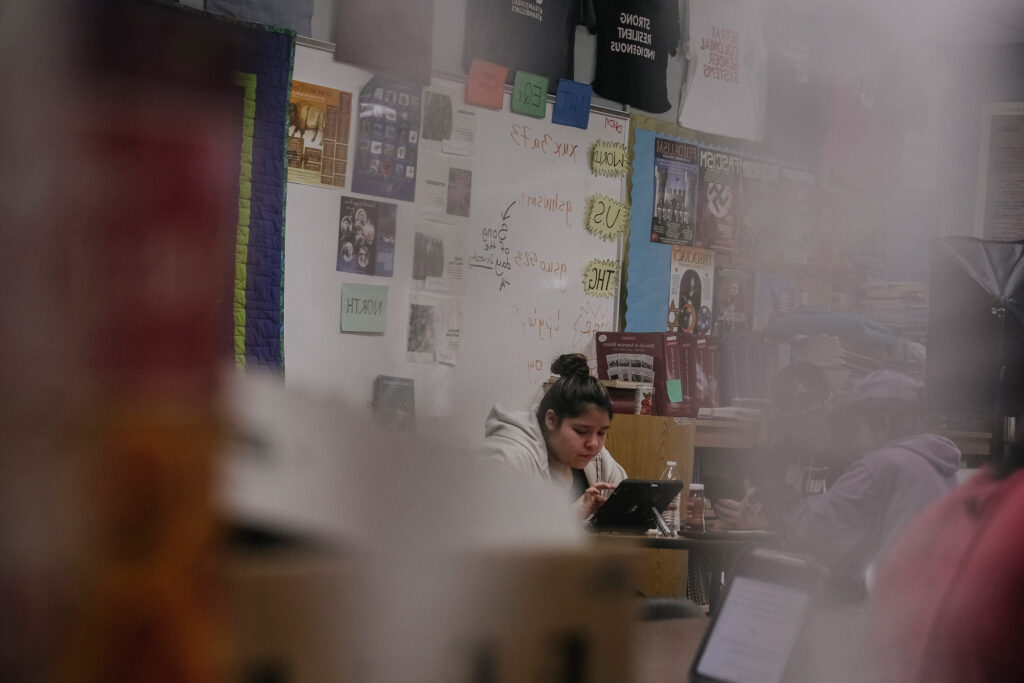

The Two Eagle River School newsletter is being advised by Jaime “J3” Stevenson in her history classroom. On the other side of the hallway, is Stephanie Fisher’s classroom.

She is the science teacher at the school and is currently building a traditional Salish canoe with the students.

Arabella Nicolai, Justice Antoine and Antone Takes Horse are in Fisher’s class. As they sit around a table preparing their presentation on how their tribe might deal with water scarcity in the future, they worry about their own future.

“All the struggles that we have to face on the reservation, not all of us can be at school all the time, and not all of us are motivated to go to school,” Nicolai said.

And Takes Horse added: “It is not even just that. Some weren’t even having full-on rides [to school].”

For many students, the school also has a history in their family. Often the students’ parents also went to the same high school. But with federal funds being cut in education, the students worry that there may soon no longer be a safe haven for them anymore.

“I got [a] younger sister [who] I would like to come here, but how things are going, [our school] might not be here in a couple years,” Takes Horse said. “But I feel like [this school] could make her have more opportunities and maybe, have her come out, like, actually be herself a lot more, rather than just being part of a clique or part of someone’s group.”

Nicolai has a cousin who was supposed to go to the Two Eagle River School this year. But her uncle has the same concerns as Takes Horse. He doesn’t want to send his child to a school that might have to close soon meaning his child might have to change schools in the middle of the school year.

At the moment, there are no concrete decisions that would indicate that Two Eagle River School could be closed. Rodney Bird, school superintendent, has been working with the Office of Indian Education and the Bureau of Indian Education and said he and both agencies are optimistic.

“We’re hopeful. We’re staying the course and just running day-to-day as if everything is the same and will be the same next year,” Bird said.

Some of the optimism comes from the fact that Native Americans are not a race, but a legal status with treaty rights. Therefore, federal acts that target diversity don’t, or should not, apply to tribes and their programs.

But he understands the political climate and the tenuous hold it has over programs like the Department of Education, concerns his students.

In the classroom, job security and the financial benefits tribal youth receive to build a life after school and to compensate for colonial disadvantages are topics of conversation among young people.

“Because now, even just this, it’s also affecting a lot of our jobs that depend on the same type of funding, like firefighting. My brother could possibly lose his job, just because of what’s going on, and that could affect money circulating in my own home,” Takes Horse said.

His classmates share his concerns. “A lot more people will be struggling to make ends meet,” Justice Antoine said.

For 18-year-old Arabella Nicolai, the new cuts make little sense, as they are not simply random government aid to the tribe but have been set out in black and white in treaties.

“That’s why the Hellgate Treaty was made. It was because of what they’re doing now. We literally had lawyers from here go up to Washington just to show them our treaty rights, to prove that they couldn’t take away our resources,” Nicolai said.

She recently joined the “Inside the Nest” project to inform her classmates about what they can do and if their benefits are getting cut, but also to make her voice heard. She also wants to report on Missing and Murdered Indigenous People.

At the Salish Kootenai College, the Spirit of Many Colors club comes together once a week. There is laughter from the room where the club members guess the words in a dictionary by drawing them. This is a game that the DuMontier siblings came up with as children.

The students sit around a large table. One member is in the process of putting “transgender pride” stickers on their motorcycle helmet. In the middle of the table is a “Tribal College” magazine. The issue is entitled “Resilience.”

About 10 students attend the queer meetings that Chula DuMontier usually leads. It is a safe space for the Salish-Kootenai and Mexican descendant, with long black hair, and her friends to give each other community and to check in with each other.

“Things have been pretty spooky recently,” the 21-year-old said. For her, these meetings are there to “just still [know] that we are worthy of providing each other comfort and having good things, feeling good things and supporting each other in that way, regardless of how we are viewed and what people might see us as.”

Chula DuMontier wants these meetings to be a place for everyone.

The Spirit of Many Colors club also does outreach to welcome new members and to spread awareness. Currently, the group is planning a talking panel, where they want to serve Indian Tacos and speak about their community and experiences as queer people.

But it is always a balance between being proud and making people aware of the community but also staying safe and not putting a target on their heads.

A balance between safety and activism

After the Walmart incident, Jet DuMontier is even more aware of this than before. They echo a thought that their partner had shared in the club meeting: “This [election] is giving the wrong people false confidence.”

In 2023, DuMontier had to cancel a public speech for the Transgender Day of Visibility because white men with guns had come to the march.

Nevertheless, they do not want to stop their outreach. Their community gives them the safety and support they need to keep going.

***

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE:

Previous

A Deeper Divide

Next

Search for survival