Surrounded by Séliš

Rigorous program amplifies efforts for Salish language transmission

Story by Madeline Jorden. Photos by Renna Al-Haj.

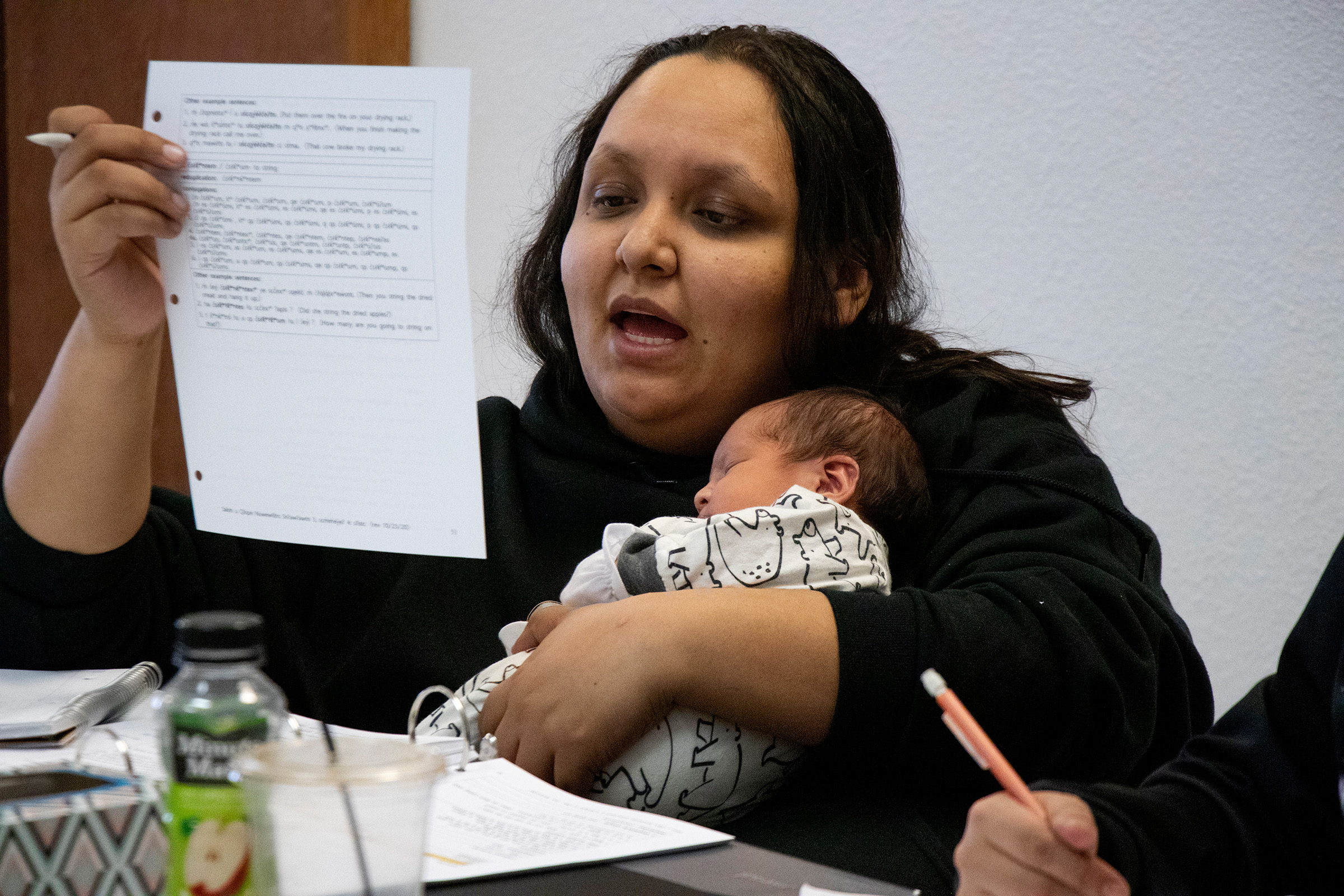

When she learned she was pregnant with her first child, her daughter Maninłp, Aspen Decker remembered the words of her teacher, the elder Pat “Patlik” Pierre, with whom she’d spent hours practicing the Séliš-QỈispé language at Nk̓ʷusm, the language immersion school on the Flathead Indian Reservation.

“You need to talk language to your kids,” Pierre told her. “It’s our kids that are going to be the ones that keep our language going and alive.”

And so Decker began speaking to her unborn daughter in Séliš. After Maninłp was born, she narrated their life out loud to her new baby. “Do you want this food? Are you ready to nurse?” she’d say to her in their ancestral language. Maninłp wasn’t immersed in an English-speaking environment until she left the Séliš-QỈispé world her mother had shaped for her to start preschool on the reservation.

Enlarge

Children are born with the innate ability to become fluent in the language used around them, usually without any explicit instruction. Research shows that fetuses in utero can not only hear some of what’s happening outside, but can also start to remember specific voices and distinguish the particular rhythm of their mothers’ language. Within the first year of life, a baby’s brain begins to ignore phonetic differences that don’t carry distinct meanings in the language.

Before children can even speak, their brains begin to wire into the framework of a particular language, and Decker wanted to make sure that her baby’s brain was forming Séliš-QỈispé patterns.

For many Indigenous people, language is closely tied to culture and tradition. Words are intimately connected to place and reflect a community’s unique worldview that is laden with meaning. “It’s your identity. It’s who you are,” Decker said. “It’s who our ancestors are.”

But tribes across the country have seen a dramatic loss of Indigenous languages in the last century. According to the linguistic database Ethnologue, 98% of the nearly 200 active Indigenous languages in the United States are endangered, meaning the traditional speakers have started teaching and speaking different languages to their children.

Enlarge

Ethnologue classifies Séliš-QỈispé as one of those endangered languages, learned as a first language only by the generation now considered elderly. In 1910, more than 95% of the tribal population was fluent in the ancestral language. By 2016, the rate of fluency had dropped to less than 1%. Today, there are only a handful of elders still alive who grew up speaking Séliš as their first language.

Many tribes have tried to reinvigorate their traditional languages with various types of programs, to varying levels of success. But with the last generation of first-language speakers passing on, there are not enough proficient adults in many communities to teach the language to the next generation. Even for those who complete immersion programs, there are few, if any, spaces to find other speakers to converse with and solidify the learned language in daily use.

The Séliš-QỈispé adult apprentice program on the Flathead reservation is attempting to address that gap through an intensive format that requires students to dedicate themselves to language learning as a full-time job.

Enlarge

Although versions of an adult language learning program have existed for several years, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribal Council agreed to provide funding in 2018, allowing the program to offer compensation at a rate of $15 an hour to its students.

The move is significant in a state where minimum wage stands at $10.30 an hour.

Paying the students is crucial, said Leora Bar-el, a linguistics professor at the University of Montana, because it recognizes the amount of time that adults need to invest to make significant progress.

“Motivation alone is often not enough,” she said. “It’s hard to learn a language as an adult, period.”

Enlarge

Every weekday at 8 a.m., the apprentices clock into work at the tribal longhouse in St. Ignatius and, for the next eight hours, are drilled on vocabulary, pronunciation and grammar. Starting with the basics, they eventually progress, over the course of two years, through a three-level curriculum that amounts to 116 college credits, or 1,160 hours of language learning.

The lessons continue year-round, with vacation days only on federal holidays, just like other employees of the tribal government.

On top of that, many of the apprentices enroll concurrently in a language teaching program at the tribal college and do additional coursework in the evenings and on the weekends to work towards a bachelor’s degree in education.

“Our apprentices, we always tell them, that this is intense,” said Melanie Sandoval, who manages the program. “You’re getting a lot of language thrown at you.”

Enlarge

Séliš can be challenging to learn for a first-language English speaker, since it involves a new alphabet, new patterns of sentence structure and new sounds that require the speaker to move the throat and tongue in new ways. “I’ve never had a headache that bad in my life,” said Daniel Brown, who was a member of the first cohort of apprentices in 2018.

In addition to the academic rigor of the program, some of the students had emotional responses that arose during their training. The deeper they got into the language learning process, the more clearly they were able to see the connection to their Indigenous identity that had been taken from them through decades of cultural suppression.

“People who knew me before think I’m so different now,” Brown said, noting that he also quit drinking over the course of the program. Today, he’s a teacher at Nk̓ʷusm, the immersive language school, and is raising his own kids in the language.

Emerging research suggests that using ancestral languages can have beneficial health impacts on Indigenous people, including decreased rates of suicide, alcohol consumption, illegal drug usage, violence and diabetes.

Enlarge

“I feel like I would have gone down the wrong path again, if I didn’t have this program in my language and culture,” said Kristina Mays, another member of the first apprentice cohort who now teaches the second-year cohort. “It saved my life.”

Over 80 people have been through some level of the adult language curriculum, and at least 18 have finished the whole program. But once they graduate, the apprentices face the question of where to go next to continue their language development.

“The program lays the foundation and shows you the way, but it’s not going to make you fluent,” Brown said. “You have to continue to push yourself, if you really want it.”

If there’s nowhere to use the language outside of the classroom, it’s easy to let that knowledge slip away after the program concludes.

Enlarge

“We have nowhere to really go to hear,” said Chaney Bell, who founded the apprenticeship. “So we really have to try and create those environments, almost artificially create these speaking places, so that we have a place to hear it and practice.”

As more adults gain access to the language, Bell hopes it will make its way into more homes on the reservation. He dreams of one day hearing Séliš-QỈispé on the radio, television, and seeing it on the menu at McDonald’s.

But some language apprentices already have another speaker within their family who they can practice the language with at home.

Mars Sandoval, a current first-year apprentice, began learning Séliš at the age of three, as one of the first students enrolled at Nk̓ʷusm. Due to that early exposure to the language, he has a verbal dexterity and natural aptitude for the pronunciation of complicated sounds.

Enlarge

When the class learned body parts, his teacher turned to Sandoval to pronounce sčkʷƛ̓kʷƛ̓us, the word for eyes, a tongue-twister of consonant sounds that are formed at the back of the throat.

“You move your mouth the same way you do for beatboxing,” he said, demonstrating.

Sandoval’s partner, Lydia McKinney, graduated from the apprentice program in 2023 but didn’t grow up exposed to the language. Her family moved to Utah for her father’s job, where the community was predominantly white.

When McKinney’s aunt, Michael Munson, who works at the tribal college, reached out to her about applying for the apprenticeship, she felt called to do it and enrolled in the third cohort in 2021.

She said learning the language felt like something she could do to help her people.

Enlarge

Before McKinney, it had been three generations since anyone in her family spoke Séliš. Now, she and Sandoval stay in the language with one another at home. Their skill sets complement each other, which allows them to grow their language knowledge in different ways. Sandoval has a natural facility with pronunciation, having absorbed the sound inventory as a young child at Nk̓ʷusm, while McKinney has a wider and deeper vocabulary, having completed the entire apprentice program.

“Before I met him there was this feeling where, I’m learning so much, but I don’t have anybody to talk to,” McKinney said. “When me and (Sandoval) got together and started talking to each other, it brought it into the real world.”

They send text messages to each other in Séliš or use the language to name the worlds they create when they play video games. But on a deeper level, it’s even more special to speak Séliš with someone they love.

“Kʷ in x̣menč x̣ʷl esya l i spuʔus,” they’ll tell each other. I love you with everything in my heart.

“It’s a stronger connection,” Sandoval said. “You get to do something that no one else is doing.”

Enlarge

After McKinney graduates from the tribal college next year with her bachelor’s degree in education, she hopes to teach at Nk̓ʷusm. She’s not as interested in teaching in the public schools, because the time she’d be able to spend with her students would be so limited. “It’s great that they can learn some language, but they’re never going to be able to achieve fluency,” she said.

To achieve the goal of making the language more accessible and widespread within the community, more proficient teachers are needed in all levels of the reservation schools. In a 20-year strategic plan for language revitalization that he authored in 2017, Chaney Bell estimated a need for at least 40 proficient teachers to fill the positions in every school, but the real number is likely even higher.

“It’s not where we want it. Definitely not where we want it yet,” Bell said of language learning in the public schools. On the reservation, where only about a quarter of the residents are Native American, the cultural will to prioritize language and culture would have to come from school boards and school superintendents that serve a majority white student body.

The legacy of excluding Indigenous language from schools stems from the establishment of boarding schools that aimed to assimilate youth into Anglo-American culture.

Just two street blocks away from the longhouse, where the apprentices sit and study the language every weekday, is St. Ignatius Mission, a Catholic church established on the reservation in 1855 by Jesuits. A nearby school was later established by the Ursuline order of nuns, where many Indigenous children were sent. A black-and-white photograph from around the turn of the century shows a line of young girls, mostly dark-skinned, arrayed before the camera in knee-length dresses.

When recent construction was done on the parking lot for the longhouse, the crew unearthed some of the old foundations of the mission outbuildings – including an industrial work room where some of the students were assigned to work.

“That’s how close we are to our history,” said Melanie Sandoval, the apprentice program manager.

Enlarge

Many of the tribe’s elders either attended the Ursuline school themselves or had family members who did before it closed in 1972. Shirley Trahan, who was born in 1944 and is one of the few remaining first-language speakers on the reservation, was kept out of the Ursulines’ school by her mother after one of her sisters passed away as a boarding student. “No one knows why,” Trahan said. “After that, my mother said, ‘None of you are going to go to school there again.’”

Although Trahan stayed at home, where she was able to speak Séliš-QỈispé with her family, the environment in the local public school she attended was also repressive. As she recalls, all of the teachers were white and punished students for speaking Séliš. “That’s one of the reasons why our language started to fade away,” she said. “It wasn’t allowed.”

While Trahan remained proud of her culture and traditions, she watched others stop speaking the language after being shamed into using English. “They were made fun of and they were mimicked and stuff like that,” she said. “It made kids and people feel ashamed of speaking their language. That’s why they didn’t speak it anymore. Those were tough times.”

Learning English also provided an economic incentive. Stephen Small Salmon, an 84-year-old first-language speaker, remembers how many people felt that they had to make a choice between living their traditional culture and going to college to pursue a prosperous life. Those that chose college often lost their language, he said.

Now, through the apprentice program, the tribe has assigned a tangible value to learning Séliš. And although paying students is essential to making it possible to devote two years to the language, some argue that it’s not enough. Daniel Brown made better money working as a bus driver, and the decision to take a pay cut while supporting a family was not easy. The apprentice contract also provides no benefits.

Enlarge

“This is hard work,” Chaney Bell said. “But it’s also awesome work. Our language is just so beautiful. It just makes you feel so good. And I just want our people to be able to have that.”

Aspen Decker’s oldest child, Maninłp, is now 11 years old. She and her three brothers are skilled Séliš speakers, thanks to the persistent instruction from their mother.

Sitting around the kitchen table of their family’s white farmhouse in Arlee, Maninłp and her 9-year-old brother Nštews watched as their mother showed them how to weave pieces of tkʷtin̓, or bulrush, into drying mats. In a gentle, even voice, Decker spoke in Séliš all the while, prompting Maninłp and Nštews to tell stories as they worked, the family speaking to each other in their traditional, tribal language.

“A long time ago when I was four years old, Maninłp had a cut,” Nštews said carefully in Séliš. “My mom said get a bandage.”

“You said sticky,” said Maninłp, correcting her brother.

“No, and be quiet Maninłp!” yelled Nštews.

“The bandage for your wound,” said Decker, encouraging Nštews to continue with his story. “Nkʷḱʷá is the name of that medicine.”

Decker believes her children are among the first to speak Séliš as their first language in more than 60 years.

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE:

Previous

A Mathematical Genocide