Before it’s Forgotten

Once held back by diversity, Little Shell tribe embraces its roots

Story by Mike Green. Photos by Walker McDonald.

As far as Indigenous music and dances go, a lively jig set to an upbeat fiddle does not seem iconic to Indigenous culture. But for Al Wiseman, the sounds of toe tapping, up-tempo fiddle playing and high energy dancing have a direct connection to his youth growing up Métis.

“It’s always been said within our people, that the Métis Little Shell people, they were born to dance, and that’s what they done for fun,” Wiseman said.

Sitting in his living room in Choteau, Montana, Wiseman became animated when he talked about the Métis music he grew up with.

“My grandmother told me that almost every man, and there was about 125 people lived up there one time in our settlement, could play the fiddle somewhat,” he said. “That means, maybe just one or two tunes, that’s all they can play. And then others could play all night long and never play the same tune twice.”

Enlarge

Enlarge

The fiddle’s importance to the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians culture is a symbol for much more. The Little Shell spent 150 years fighting for federal recognition. The state of Montana recognized the Little Shell as a tribal entity in 1990, but the federal government didn’t agree until 30 years later, in 2019.

Without recognition, the Little Shell had no reservation, no centralized land base for its people to converge to share and evolve customs and culture.

Today, five years after the tribe received federal recognition, its members are working to embrace and protect their diverse history. A history and culture that includes not only the people’s history as descendants of the Pembina Chippewa band, but also their roots in French and Scottish traditions.

Traditions like jig dancing and the fiddle were inherited as French and Scotch trappers began to integrate into their society hundreds of years ago.

With federal recognition, there has been a resurgence of energy from those trying to learn about the people they descended from and their culture.

Federal legislators had balked at recognizing the Little Shell as a tribe for decades, citing the vast diversity of its people. This meant the tribe did not meet two criteria for federal recognition: proof that the tribe shares a distinct community and culture predating colonial history, and proof that the tribes’ citizens share a lineage and all descend from the same historical Indian tribe.

—

For more than 20 years, Louella Fredricksen worked in the Little Shell enrollment office, helping people who hope to become enrolled citizens verify their genealogy for enrollment.

“Guess I’ve got to put my teeth in!” she said, followed by a laugh that punctuated many of her sentences.

Enlarge

Sitting in her kitchen, the walls are lined with aged photos of family members, books on the Little Shell, and tucked along the wall are four thick, white binders. As she lifted one off the floor, corners of papers and photographs are visibly sticking out.

“I think it’s exciting, its like a puzzle, you find this, then you find that!” Fredricksen said as she opens a notebook containing her personal genealogy work. “Then you go somewhere else and you find something else.”

Her own path started with a book called “Strange Empire” by Joseph Kinsey. The book started a journey to find out who she was and to verify she met the one-quarter blood quantum, the amount the tribe required for enrollment

“Then after that book, I went to Canada trying to find out about my ancestors,” she said.

While Fredricksen met the blood quantum requirement, some still cannot enroll in the tribe because their blood quantum is too low.

“The whole tribe, full-bloods are gone, no full-bloods,” she said.

The tribe self-identifies as the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians, and includes in its people Chippewa, Cree and Métis people — all of whom are descended from the Pembina Chippewa band.

Enlarge

Métis is a French word that translates to “mixed blood.” The Métis people are descendants of Native and European ancestors. The Métis are recognized as an Indigenous group in Canada but remain unrecognized in the United States.

Enlarge

“I finally did do Ancestry,” Fredricksen said, in April, “I got a message from them like a week ago, surprised me and it says, ‘Do you know that, I think, 87% of your family came from Canada?’”

She again punctuated this statement with a laugh.

Throughout their history in the United States, Métis people were often cast aside and moved off their lands. In Great Falls, they were forced to live in squalor on Hill 57. Today, the tribe has secured land on Hill 57, where the tribe’s cultural center now stands and will soon be the site of its new powwow arbor.

In Choteau, the tribe’s citizens had a small settlement, in Teton Canyon where they lived within their community, maintaining their traditions and teaching the next generations. Today, their history in Teton Canyon is marked by a small cemetery located within an easement granted by The Nature Conservancy.

This site has long been cared for by Al Wiseman. He recalled his childhood running through the trees of Teton Canyon surrounded by citizens of the Little Shell Tribe.

“I pretty much know a lot about the old ways. Lived a lot of it myself and a lot of it what was going on eons before me,” Wiseman said. “But I still learned a lot from my elders.”

Wiseman is respected deeply in the Métis community as a historian and culture keeper. He has shown up throughout his life to make sure the history of the Métis in Montana is taught and accessible. He has created two footlocker programs of items that represent the Métis history and are available in Great Falls to be checked out and used as educational items.

Wiseman also acknowledges that in many ways, the tribe has lost some of its old ways.

Enlarge

“I say, you know, the old ways are gone. And we lost our land. So we got to make the best of it, and just go to work and be a good citizen and do what you can do. That’s the way I look at it”, Wiseman said.

For Wiseman, this has looked like a life of dedication to place and the culture of the Métis.

Driving up to Teton Canyon, he easily picked out the indentations left from centuries of travelers between juniper trees and sage brush, as they utilized the Old North Trail to travel along the Rocky Mountain Front.

Since 1975, he has taken care of a sign at the mouth of Teton Canyon, sharing the story of Métis people in the area.

“You know what I use to paint those letters?” he said, pointing to the clean yellow lettering. “Pipe cleaners! Works like a charm.”

Enlarge

After nearly 50 years of caretaking the sign, he is ready to pass it onto the next person. The person who stepped forward to take on the responsibility was a local forest service ranger, not a citizen of the tribe.

Up Teton Canyon, Al Wiseman moved steadily over snow and wet ground on a walk he has taken countless times.

He leaned on his walking stick, the handle wrapped in red, white and blue paracord. The cemetery he stood in has been under his watch almost as long as the sign. He has spent a good part of his life watching over this plot of land.

He shared quietly how though he has spent much of his life taking care of this ground, he does not think he will be buried there.

“I just don’t know that anyone is going to come to take care of it.”

—

Enlarge

Alisa Herodes is on the Little Shell Tribal Council, runs a cabinetry business and is also the head of the Little Shell Pow Wow committee.

She remembers her grandmother saying, “Do you know you’re Indian?” one night after dinner when she was about 10 years old.

Herodes remembers her grandmother fondly: the bags of M&M’s she’d give them when they learned how to snap their fingers, cross their eyes and the cats in the cradle string game.

“And that’s when she stopped bringing candy and brought a scarf and I didn’t realize the Native ties to that scarf,” Herodes said.

“Early on, I don’t remember ever seeing the metallic thread, the very floral scarves and I had no concept that that was a cultural thing,” Herodes says, “I remember thinking, ‘Man, I miss those M&M’s,’ I think about it now and I just shake my head, grandma tried.”

Enlarge

The image Herodes paints of her grandmother has now come to envelope what it means to be Métis. Things she didn’t recognize at the time as being part of their culture have now been represented every year at their powwow.

“The tea drinking, Bible carrying, jigging, fiddle, mandolin, guitar playing woman,” Herodes said of her grandmother.

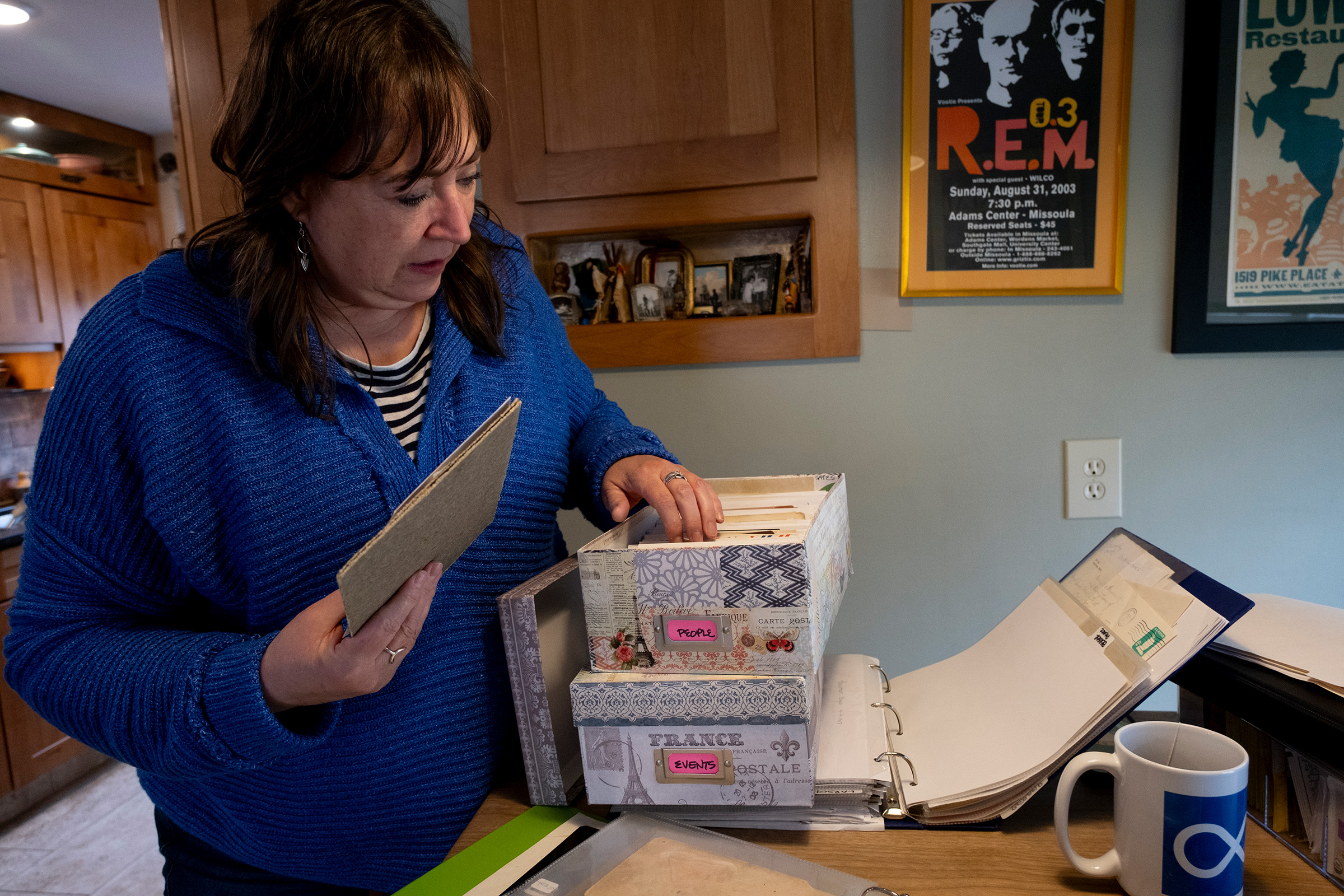

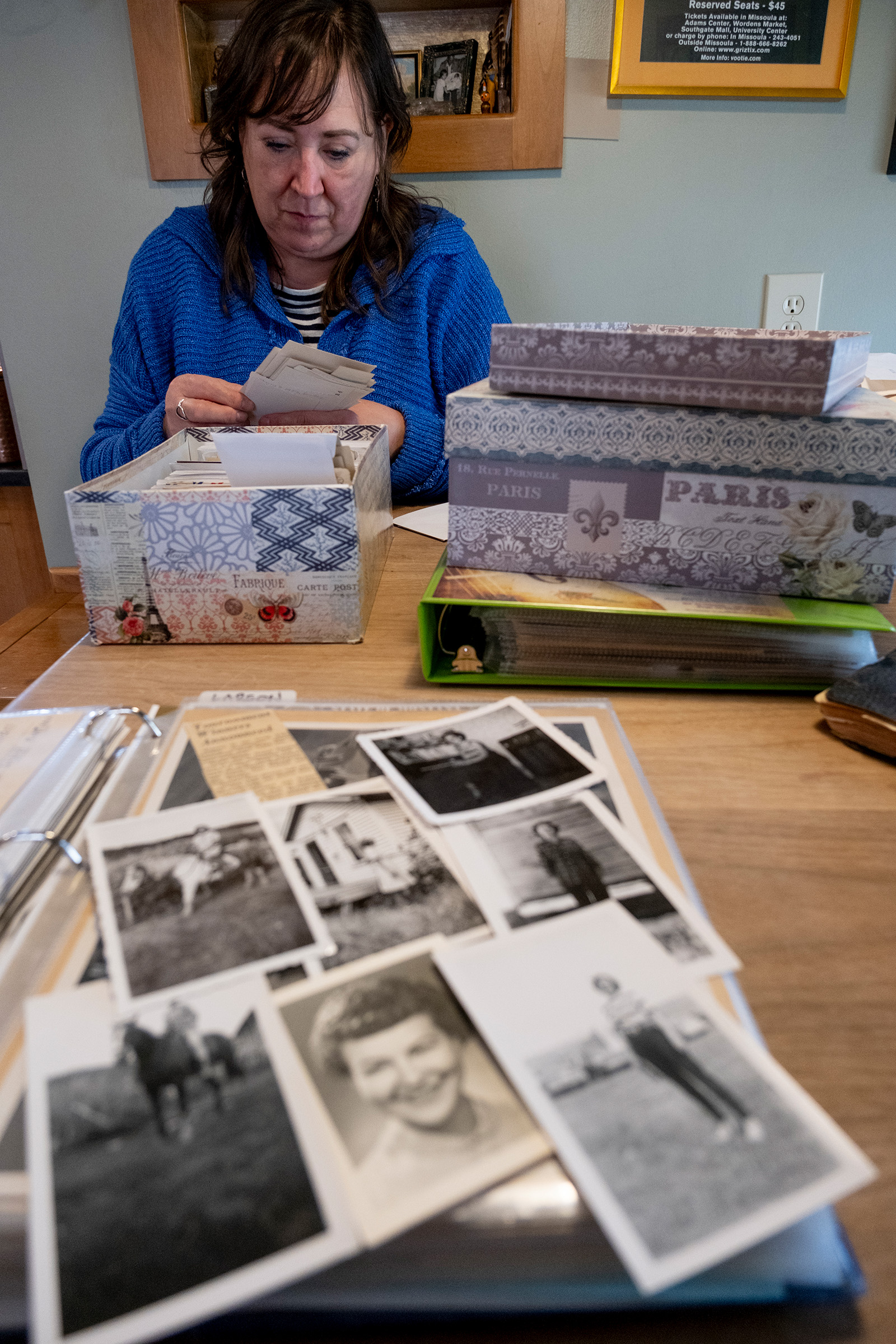

When her mom died, Herodes and her sister began cleaning out their mom’s house. As they began going through boxes, they started to uncover parts of their family history they had never known.

There were boxes of photographs, pages of writing and pieces of a family history she had not known deeply. This started a journey of discovery much like that of Louella Fredricksen.

Many Indigenous people today were raised by parents who grew up when practicing their traditions was illegal for most, if not all, of their lives.

Enlarge

Enlarge

It was not until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 that the United States Government legalized and allowed Indigenous people to practice their traditional religions and ceremonies. Up to this point, and in many ways afterwards, the federal government actively worked to remove Native American peoples’ identity and culture from the landscape of the United States.

In every Indigenous community across the U.S., the traumas and the effects of cultural genocide, boarding schools and prejudice are still being uncovered. Many people, who could now be considered elders or are raising children of their own, were raised at a time when their parents were not accepted for being proud of being Indigenous. In many cases, they instead hid that fact.

Many in that generation are now working to bring energy back into their culture and pass it on.

—

In the shadow of Hill 57, a place once known for its destitute living situations, the Little Shell tribe is rebuilding. In addition to the cultural center and the future powwow arbor, there is also an elders center.

Inside the center, Mike LaFountain walked slowly back and forth as he talked to the 10 people gathered before him.

He began a monthly class aimed at teaching cultural traditions to youths. So far though, the classes have mostly been filled with older people.

“I want these kids today to be proud of who they are and voice that,” LaFountain said. “To become leaders and voice what has happened.”

He explained to the group that they are going to play a game of telephone, much like the one played in schoolrooms around the country. This game, however, had much more at stake, metaphorically.

“This card is your existence,” LaFountain said as he passed playing cards to each person. “If you mess up the story, you lose your existence, your identity.”

Enlarge

His frame dwarfs his folding chair when he sits. Standing at 6’5” and having spent much of his life competing in both powerlifting and arm wrestling, he is barrel-chested and imposing.

Of the group assembled, there were only two people in attendance under 40 years old. The first was his son, Duane, 18, and the other was a nine-year-old girl whose stepfather brought her.

LaFountain began the lesson talking about the importance of storytelling in his own life. He shared how from an early age, he found himself drawn to the elders in his family and the traditional way of life they were raised with.

He stressed the importance of retelling stories exactly the way they were shared, and this tradition being the foundation of orally transmitted cultures like their own.

“It was so important to our people, every winter, every summer, how to get to a camp.” LaFountain said. “It was our existence, our survival.”

He allowed the class to do whatever it needed to remember the story word for word by writing it down, recording it — anything.

Enlarge

The story moved through the room slowly. Each person took their time to check and recheck every part, they made sure they had done it perfectly, so the next person would be able to pass it on word-for-word.

Everyone writes down the story, until the sixth class member. She does not write it down, instead she only listens and shares it orally. Everyone in the room notices the change.

When the story reached its final recipient, it will be almost perfectly intact. Just one slight change, a red blanket within the story never finds a bed.

LaFountain traced the path of the story through each person in the room. Each class member read out their notes in the order it was passed. Aside from some nervous mistakes reading, it stayed the same until it reached the woman who did not write anything down.

The card of the woman who received the story from her is flipped over, taking her existence from her.

“Our identity stopped here,” LaFountain said before flipping over the card of each person that came after her.

“You wiped us out!” one person jokingly said to a few hushed laughs.

“We have an obligation, as a warrior society, to pass down our traditions, and teach them as they were taught to us” LaFountain said to the group.—

Enlarge

Even with federal recognition, the Little Shell tribe continues to evolve. Wiseman sees even the diverse influences of his tribe beginning to fade, dissolving into larger society.

In June, Wiseman has planned a three-day Métis festival in Choteau. However, he is having trouble finding people who can still play what he calls “Indian fiddle music.”

“But when you’re trying to put on a festival, you know a true festival, you want to try to keep your food, dancing and everything,” he said, “you want to try to keep that as close to home as you can.”

He’s referring to music like that of an act called The Métis Fiddler Quartet from Canada. The music is lively and complex. A music expert might notice unique time signatures that separate the songs from traditional French, Scottish or Irish styles of the same types of songs.

“But all of our fiddle players, they’re gone,” LaFountain said. The fiddle players that are around tend to play more progressive styles. “And there’s a world of difference between your progressive music and the old Indian style of music. (A) daylight and dark difference.”

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE:

Previous

Piinomaatskoo”sit’