Staying Séliš

Protecting tribal traditions amid a changing landscape

Story by Sabrina Fehring, Photos by Reed Lindsey

The students had to hurry. During a morning in March, a thick layer of snow covered the high peaks of the Mission Mountains. There were bits and pieces of snow surrounding the grounds of St. Ignatius High School. But most of it had melted away, so time was short.

Aspen Decker, who teaches Séliš language and culture, abides closely to her tribe’s culture as taught by her elders. That means the time is short to tell coyote stories, which can only be told when snow is on the ground. Due to climate change and milder winters, there are fewer days with less snow.

“They’ve always told us when there’s no snow you can’t tell coyote stories, or the snake will bite you,” Decker said. “So, we have to choose whether to listen to what our elders want or keep coyote stories alive even if there is no snow.”

Coyote stories are the Séliš-Qĺispé way of teaching culture and traditions.

“Coyote is a trickster guy who’s doing different things to help humans,” Decker said. “There are morals to the story of what to do or what not to do.”

Decker is one of few fluent Séliš speakers on the Flathead reservation. Teaching her students the Séliš language and culture is vital to her. In class, they started to create their own coyote stories.

“Your stories can be about any animal,” she told the students.

She raised her arms wide in a U-shape, displaying antlers.

“What’s that animal? Tšeć.”

The kids mimicked her, raising their hands, and repeating the Séliš word. “Tšeć. Elk”.

“What do we do for moose?” she asked.

Their arms opened wider. “Sx̣áslqs,” the kids repeated.

Aspen Decker spreads her arms while showing her class at St. Ignatius High School the traditional sign for “Sx̣áslqs,” the Séliš word for moose. Despite the decline in Séliš speakers on the reservation, Decker hopes to revitalize the language through her teaching.

The oral tradition has been maintained for thousands of generations. Germaine White, who used to work for the cultural resource management and the tribes’ natural resource department explained the importance of coyote stories.

“That’s our history book. The stories tell us about our way of life,” White said.

The Montana Climate Office is already seeing changes in snowpack. The rising temperatures cause snow to come later in the year. Predictions also show expectations of more rain instead of snow.

Climate change affects the Séliš-Qĺispé in several ways. Some effects are obvious, rising temperatures are limiting the window to tell winter coyote stories; climate migration and fires put a stress on natural resources directly linked to culture. Some effects are not as obvious. Porcupines on the Flathead reservation seem to have disappeared; plants are blooming earlier, shifting traditional ecological schedules. These effects are likely to continue as the climate continues to warm.

“We’re seeing a four- to five-degree Fahrenheit increase in annual average temperatures over the Flathead reservation,” said Kyle Bocinsky, the director of climate extension at the Montana Climate Office.

***

Seeing the climate changes and how they are entangled with traditions and culture, many tribal members are devastated. Traditions and landscapes are changing. Their elders had to go through adapting in the past. Now the Séliš-Qĺispé have to adapt once more to human-caused events.

In Séliš-Qĺispé culture, many traditions are linked to the seasons. In the cultural calendar Séliš words name the months of the year indicating when certain plants bloom or when hunting begins. May, for instance, is S¿eém, the month of the bitterroot.

Early in the spring, Decker and her family headed out to harvest cedar bark to create baskets. Decker needs the baskets for gathering plants. Although bitterroot is not supposed to be due until May, Decker already saw people posting pictures of bitterroot.

“It’s three weeks to a month ahead of time,” she said.

She has noticed drastic changes in the blooming of plants within the last decade.

“Our calendar has changed so much that we have to start documenting on our own to know when plants are going to be ready so we don’t miss them,” Decker said.

Her black GMC Yukon rumbled and shook as it drove miles up the mountains behind Arlee on a gravel road. After a while, the car stopped in the middle of the road. They had reached one of their gathering spots. Decker grabbed her ax and, followed by her two children, went into the woods. Climbing across trees and branches in her high-heeled boots, she headed towards one cedar tree.

Together, they started singing prayers while slowly pouring out tobacco. “I always make sure I give something back,” Decker said. It is what she has been told by elders, reciprocity.

After praying, Decker grabbed her ax and started separating the bark from the tree. The sound of chopping was accompanied by the sound of birds pecking, and the laughter of her three-year-old and seven-year-old sons climbing through the woods, branches cracking underneath their feet.

After a while, Decker stopped chopping. She made sure not to cut deep into the tree. If the cut is not wider than two hands the tree heals itself. But trying to get the first layer of bark off is hard. The wood is too dry.

“At this time of the year, it’s usually really wet,” she said.

She grabbed her ax again, chopping off a bit more. Sprinkles of wood were shooting off in every direction. Tiny pieces of wood landed in Decker’s hair. Still, no luck.

“We will have to come back for this tree another time,” she told her daughter. They got back into the truck to drive to another spot. Finally, some luck with the paper birch tree. Decker managed to peel off two pieces of bark, ideal to make small birch bark baskets. That tree was also drier than normal.

“We’ve had a particularly dry winter and warm spring,” said Bocinsky, the director of climate extension. “Some of the projections would suggest that those trends are likely to continue.”

With drier weather, the fire danger grows. The route to the gathering spot lead past huge piles of logged wood. To minimize the risk of wildfires the tribal forestry has thinned the forest.

“They had to take out some trees and bushes where I usually gather so I had to find new spots,” Decker said.

The threat of wildfires threatens an important native tree species: whitebark pine. “Whitebark pine is one of the first foods. The seeds were used as a protein source,” said ShiNaasha Pete, who works for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Forestry Department.

Pete’s work focuses on the reforestation of white-bark pine. Although she is a Navajo tribal member, she grew up in the Flathead area and understands the natural and cultural importance of whitebark pine.

“The trees have been here longer than us and they have a lot of teaching with them,” Pete said. “I know we’ve lost a lot of that cultural connection over time, but we have to keep that cultural connection with those stories and tribal teachings because we don’t know what will happen in the future.”

Highway 35, on the east shore of Flathead Lake, trails along the lake’s shore. An ocean of fir trees stretches out on the right side. Every now and then the road passes an almost empty range, filled with broken off trees and dark, black roots. Especially last summer, fires destroyed huge parts of the forests along the Mission Range.

Looking at the forests from afar, acres of shades of brown become evident among the lush green. Those are the spots where whitebark pine grows, at high elevation, closely underneath the nearby mountain peak’s snow belt. Nearly 80 acres of whitebark pine burned last year.

Apart from fires, two climate-related factors further threaten the pines. Insects survive milder winters, including the beetles that are killing off the trees by tunneling underneath the bark and laying larvae.

Another factor is a fungus called white pine blister rust, a foreign disease originating in Asia.

“These trees have never been introduced to it in these areas and so there wasn’t a way for them to adapt,” Pete explained.

With climate change, everything is happening a lot faster. When the beetles attack a whitebark pine that has the infection of white blister rust, the tree dies more quickly.

To keep the pines alive, the tribal forestry department started a reforestation program. Studying the pines, they found a genetic resistance to the blister rust.

Two greenhouses on the reservation are designated to grow different tree seedlings, among them are whitebark pines equipped with the genetic resistance.

The large greenhouse can house up to one million seedlings.

1. ShiNaasha Pete and her restoration team ensure the conditions of the greenhouse are optimal for the trees. Water, humidity, heat, and time are necessary for the saplings to thrive. 2. Genetically-resistant whitebark pine saplings take two years to grow before they are able to be planted on the high elevation ridges of the Mission Mountains. 3. Forestry restoration leader ShiNaasha Pete looks over whitebark pine saplings at a large greenhouse used for the tribes’ restoration work. Fire, disease and invasive species threaten the whitebark pine’s habitat.

Entering the first of two greenhouse rooms, a massive wave of humid heat hits Pete’s face. Tags on the seedling boxes show the names of the seedlings that are grown in this rainforest climate: limber and ponderosa pine.

Continuing along the aisle, the next room welcomes Pete with slightly milder temperatures. This is where the whitebark pine seedlings grow. The miniature trees are hardly bigger than a thumb. The seedlings stay in the greenhouse for two years until they are planted in the forest.

Pete’s eyes twinkle as she gazes around.

“I’m doing this for my great-great-grandkids of the future,” she said. “I hope that you know this forest is still here and that it’s still bountiful for them to have an opportunity to experience what we’re experiencing.”

***

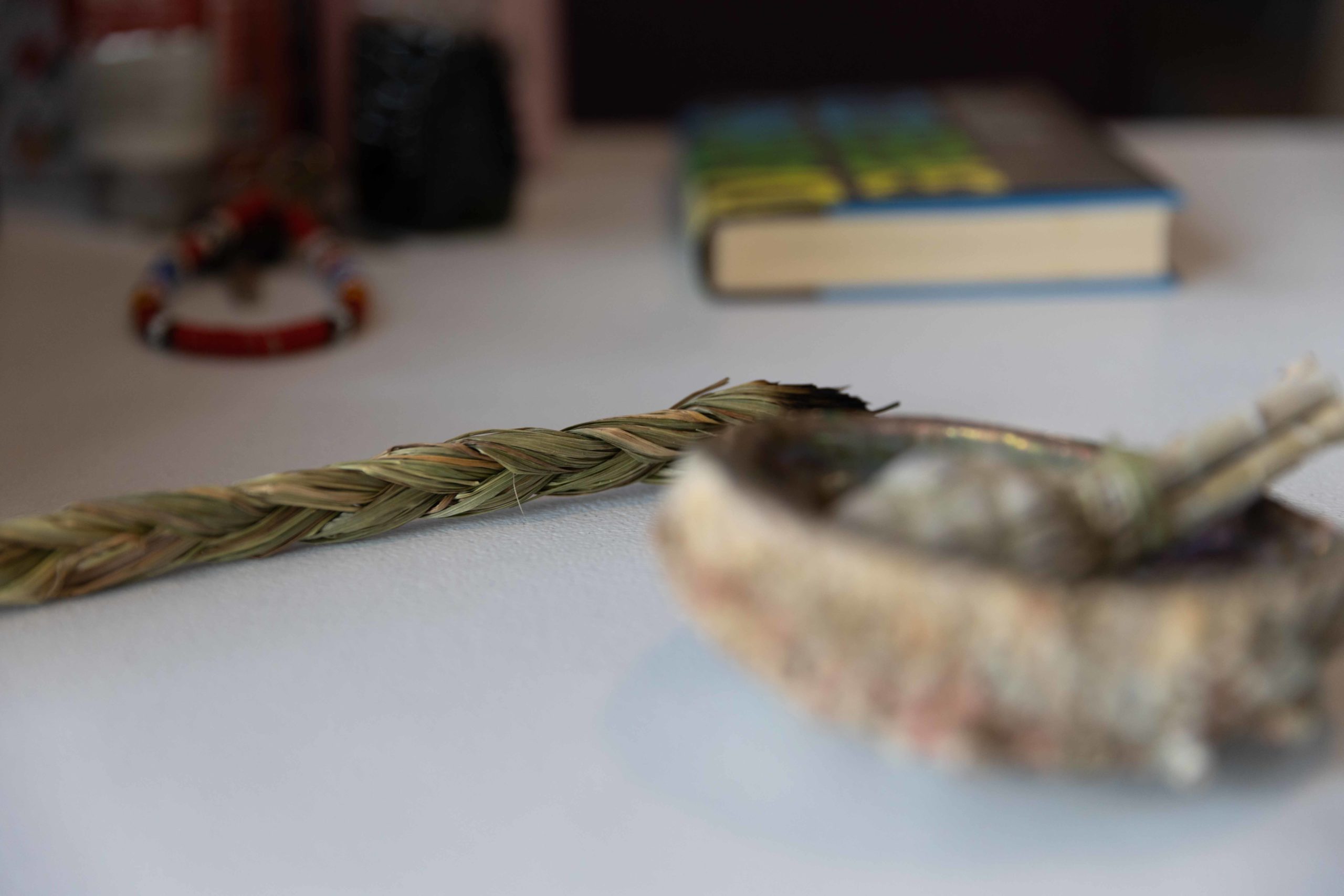

Wildfires not only affect native trees but also animals. Porcupines are losing their natural habitat. The animals are culturally important to the Séliš-Qĺispé tribes. Their hairs and quills serve for designing ceremonial clothing, moccasins and head accessories like roaches and rosettes.

It has become increasingly harder to find porcupines in the Flathead region.

A report by the Montana Fish Wildlife & Parks Department from 2015 noted a decline in the porcupine population in western Montana. This specifically counts for higher elevations above 4,000 feet – like the Mission Mountains.

Possible reasons are wildfires and beetle epidemics caused by climate change. Kya-Rae Arthur, a student at Salish Kootenai College, knows that porcupines have their nests in trees. Thus, wildfires affect them directly as their nests get destroyed and there is no way for them to quickly escape.

Arthur is passionate about creating designs and accessories with porcupine quills.

“It’s an important part of our self-identity,” she explained.

Prior to European contact, many tribes had quill-work societies, Arthur explained. Tribes would socialize with other tribes, gather quills together and exchange their artwork.

“It’s like a piece of you, a lot of people have designs that are associated with their families and tribes,” Arthur said. “It’s a way to identify who you are, where you come from, what you represent.”

In recent years, people had to move to alternative materials, like artificial porcupine hair for roaches and beadwork designs instead of quills. Beads were introduced to the tribes through European contact. To Arthur, it feels like a loss of culture.

“That’s why I’m a big advocate in teaching that stuff because it was the original artwork.” To keep the tradition alive, she teaches classes on quillwork.

It is also the strong connection she feels to the animal. “If you take the quills off the animals, you can’t help but build a relationship with that animal and appreciate the art you can make out of it,” she said.

When Arthur goes out to harvest porcupine quills, she takes a piece of fabric with her to throw it onto the animal. As the porcupine is startled it shoots off quills for self-protection. Once taking the fabric off the animal it runs away, “it’s great that you can harvest the quills without harming the porcupine,” she said.

One porcupine gives enough quills to last up to a year. Arthur uses quills mostly to create earrings.

The first part of the process is to wash off dirt and natural oils and sort out the intact quills. The next step is to dye the quills in different colors.

“Then I use the quills to either flat stitch or weave designs to create quillwork,” Arthur explained.

To create a hoop earing for example, the colorful quills can be weaved around a circular base like raw hide by folding multiple short quills around the base.

It has become increasingly harder to harvest porcupine quills.

“The last time I saw a porcupine was maybe three or four years ago,” Arthur said.

She finds herself buying porcupine quills from vendors to make sure that she can keep this art alive. She does not know when she will see the next porcupine.

***

1. Looking east, Tribal Chairman Tom McDonald admires the view of Flathead Lake and the Mission Mountains. McDonald believes an influx of new residents to the Flathead is increasing environmental pressures on native species. 2. Flathead Lake is currently described as oligotrophic, which means lacking in plant nutrients, a direct result of human interference. However, data from the Flathead Lake Biological Station indicates that nutrient levels are increasing.

Besides the habitat loss through wildfires, human presence adds to the destruction. New people are moving to the Flathead area.

“Humans are settling for home and recreation,” Arthur said. “But they are also destroying the animal’s habitat in the process of doing that and I don’t think they realize that.”

CSKT Chairman and biologist Tom McDonald knew about the decline of porcupines. He sees a direct link between loss of habitat and climate change.

The 1904 Flathead Allotment Act made it easier for non-Indigenous people to purchase land on the Flathead reservation. The number of people moving to the area has drastically increased in recent years, according to McDonald.

“We had a high influx of people moving into western Montana and the reservation just in the last three years,” he said.

Erin Leonard, an employee at Lake County Vehicle Registration, made the same observations, despite only having worked there for six months.

“The amount of people moving here from out of state is unreal,” she said.

Ashlee Terry from Century 21 Big Sky Real Estate, also agreed.

“Especially since March 2020 the market skyrocketed compared to five years ago,” Terry said.

The office does not track exact numbers but Terry has seen a huge increase of requests on the housing market.

The Flathead region is going to face an increased number of hot days and overall rising temperatures, Bocinsky explained. Still, the area is becoming a popular place to live.

1. A family takes a group selfie as the sun sets on the northern shore of Flathead Lake. 2. During the final minutes of daylight, the sun’s rays sweep across the surface of Flathead Lake.

“We see climate migrations happening, people moving from the southern Rockies and desert to western Montana,” Bocinsky said. “I think people feel that the weather is more within human tolerance.”

During the pandemic, more people shifted to working remotely. Relocating got easier.

Nevertheless, increasing numbers of people are putting stress on natural resources.

“We have people that go to their same spot to pick huckleberries and like this last year, they couldn’t even go there because it was full of new people,” McDonald explained.

To prevent losing natural resources and culture, the CSKT developed a regularly updated strategic plan addressing climate change effects and what measures to take over the next decades. Culture has a high priority in that plan. The major approach to achieving cultural action and goals is education.

Part of the education stepstone is the environmental-focused student-led group EAGLES that is doing several climate mitigation projects in every middle and high school on the reservation. Projects involve recycling and school gardens.

Siarra Mattson, a senior student in Decker’s class, is happy that her school participates in recycling.

She and her classmates already recognized shifts in the seasonal calendar. They worry how much it will continue to change in the future.

“I think the weather is going to throw everything off balance,” Mattson said. “We as people are kind of ruining the climate. I don’t know how much longer it’s gonna be prosperous.”

Working on their coyote stories, the students talk about what their culture means to them.

“Culture means a lot to me because it’s a way to get in touch with your past and where you originate,” Mattson said.

With fears for the future, there is also hope. The Séliš-Qĺispé are determined to battle climate change and save their culture. McDonald is convinced that the people living on the reservation can help with climate mitigation.

“Big changes start local. So, if everybody does it eventually you start a movement,” he said.

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE:

Previous