Banking on a Band-Aid

Funding Indian Country’s response to Coronavirus

Story by Megan Castle, Madeline Broom and Katie Hill

Fort Belknap does not have a hospital equipped to deal with critical patients. For a reservation of just over 5,000 people, the combined number of hospital beds and ambulances they have can be counted on two hands. The health center does not have a single ventilator. And if it did, there is not enough staff to operate them.

There are currently no cases of COVID-19 on the Fort Belknap reservation, likely because the tribe acted fast in their efforts to subvert the virus with shut downs and recommended quarantining. But as COVID-19 begins to slowly trickle into Montana’s Indian Country, tribal leaders and healthcare officials have to be cautious moving forward. If COVID-19 hits the reservation, it could be devastating.

“We’re worried that when it gets here it could just spread like wildfire,” said Warren Morin, a Fort Belknap tribal councilman.

Tribal healthcare facilities largely rely on funding and supplies allocated to them through the Indian Health Service, the federal agency tasked with meeting the medical, behavioral and community health needs of Native Americans.

Despite a recent flood of federal funding to help the Indian Health Service treat tribal communities, the people it serves are wary of whether or not the program can adequately care for communities in a worst-case scenario. Past experiences of IHS negligence are leaving some people who depend on IHS feeling unsupported. Some others, including health administrators, are convinced IHS is doing the best it can.

As of April 27th, IHS reported 48 confirmed cases in the Billings region, which includes Montana and Wyoming. A majority of those cases are from Wyoming’s Wind River Indian Reservation, home to Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes. Only three of the confirmed cases were in Montana, on the Fort Peck and Blackfeet reservations.

IHS, a government agency under the Department of Health and Human Services, is often criticized for its efficiency, its level of service and overall funding. The often inadequate healthcare services provided to Native Americans are issues that have always existed — but COVID-19 is pushing these flaws and uncertainties to the forefront.

“We depend on the government to help us,” Morin said. “We have some of the poorest people in America here and sometimes we’re forgotten.”

Fort Belknap’s “worst-case scenario” plan is to transport any critical patients to nearby hospitals in Billings, Great Falls or Havre. But even deciphering how that would play out is challenging.

It would take an estimated four hours to transport a single patient from Fort Belknap to St. Vincent Hospital in Billings. This estimate includes both the time en route and the time necessary to disinfect the ambulance between patients. And with only three ambulances at their disposal, if four or five critical patients come in at once, the facility would be overloaded.

There’s no guarantee that Great Falls or Billings hospitals would even have the space and resources for critical patients coming from outside of their own city. Morin wonders if there would be available ventilators for his people.

With so many unknowns about how and when COVID-19 will hit Montana Indian Country, tribal leaders have a lot of questions and few concrete answers about how to best fix them.

“I think IHS is doing the best they can with what they have,” Morin said. “But we don’t have the level of care, and that concerns me, but we’re going to make do.”

“We were at the breaking point before this,” said Frizzell. “People who come into our communities have a huge potential to compromise all of us.”

Underfunded, Overstretched

IHS was established in 1955 after the passing of the Transfer Act of 1954, which relocated the maintenance and operation of tribal health facilities to the federal government. The Transfer Act further established that the federal government has not just a moral obligation, but a legal responsibility to provide adequate healthcare for Native Americans.

Yet, public health officials say that IHS is underfunded and has been for decades.

“There is documentation we’ve been working on for years and years that blatantly describes a level of need that has never been met at 100%,” said Linda Frizzell, a public health professor at the University of Minnesota and an elder with the Eastern Cherokee and Lakota tribes. “It ranges anywhere from 40 to 60%.”

Frizzell’s main concern for her reservation in northern Minnesota is with overloading the local healthcare system. She said the same is likely true for reservations across the country.

“We were at the breaking point before this,” Frizzell said. “People who come into our communities have a huge potential to compromise all of us.”

The pandemic has only magnified how difficult it is to access federal funding for tribal health centers.

After President Donald Trump declared a national emergency in March, Public Health Emergency Preparedness program funds were made available to states and certain localities through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While these funds are not accessible to tribes, legislation currently sitting in congressional committees has the potential to change that.

But like the rest of society, tribal members don’t have time to waste. And on top of that, the funding that has been allocated to IHS has been slow to be released, Frizzell said.

Money Matters

The financial needs of IHS have been included in federal aid packages dedicated to COVID-19 since the beginning of March. But understanding how the money is allocated and distributed requires patience, a calculator, and a constant re-running of the numbers.

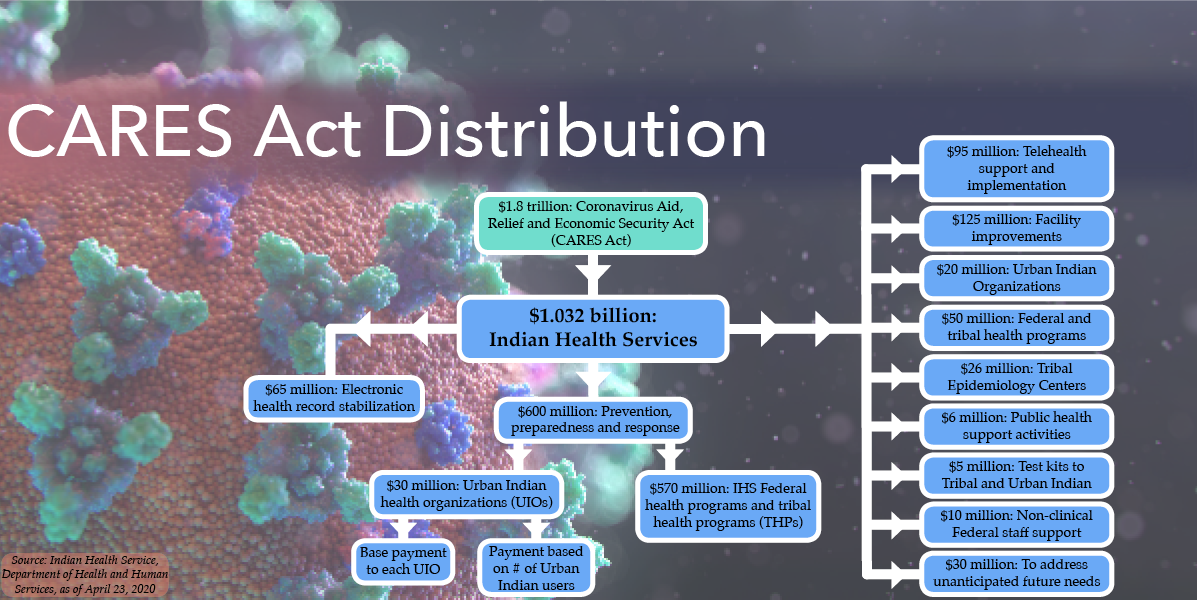

Graphic by Alyssa Stokovich

Throughout the spring, Congress has appropriated more than $1.1 billion to IHS:

· On March 6, the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act gave $70 million from the Public Health and Social Services Emergency Fund; $30 million went to IHS federal health programs, and $40 million paid for personal protective equipment from the IHS National Supply Service Center.

· Nearly two weeks later, another $64 million was allocated through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act on March 18; $61 million, went to IHS federal and tribal health programs and $3 million went to urban Indian organizations.

· On March 27, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act, known commonly as the CARES Act, allotted IHS a tidy figure of $1.032 billion. On April 3, IHS announced $570 million would go to federal and tribal health programs, while $65 million would be for stabilizing electronic health records and $30 million would go to urban Indian organizations.

Allocation decisions for the remaining $367 million of the CARES Act took another 20 days. When IHS did release those allocation decisions, the money was broken up into nine different portions.

Delayed action on federal funding has been problematic for all functions of Indian Country, not just for those trying to meet healthcare needs. It took Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt six weeks from the passage of the CARES Act to announce plans for the release of $8 billion to tribal governments from the Coronavirus Relief Fund, a source of fiscal support for state, local and territorial economies. Allocation was based on tribal expenditures in the 2019 fiscal year.

Tom Udall, New Mexico Senator and vice chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, made a public statement reflecting a widely-held sentiment that is getting dangerously close to becoming a broken record.

“The Treasury’s announcement is the definition of ‘too little, too late,” Udall said. “It comes weeks after the deadline and billions of dollars short.”

Some of Montana’s facilities were quick to see installments of federal funding. The Missoula Urban Indian Health Center, which changed its name to All Nations Health Center on May 1, had received $45,000 to defray costs associated with screening and prevention by April 1, according to the center’s director D’Shane Barnett. It has received other installments since then.

A shortage of personal protective equipment keeps All Nations Health Center closed through early May due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It uses telehealth to consult with patients instead. Photo by Sam Pester

“We were able to allocate a portion of the funding to a mobile clinic for seeing patients in isolation,” Barnett said. “People can wait in their cars before being brought into this mobile center, and it’s completely sanitize-able between visitors. No one has to sit in waiting rooms.”

Barnett expects the mobile unit could take four-to-six weeks to arrive, but said he is very excited for how it could help with future outbreaks of other viruses, namely the flu. He is quite appreciative of the support the Missoula Urban Indian Health Center has received from IHS.

“This is the first time in 25 years that I’ve seen the health of American Indians included in such a national effort,” Barnett said.

Even though IHS also helped by providing masks from the National Supply Service Center in Oklahoma City, Barnett is waiting for personal protective equipment, namely gowns and eye shields, to arrive before opening the center back up to Missoula’s urban Indian population.

“My job is to keep my staff and patients safe,” Barnett said. “We are not going to open up again until we are sure we can do that.”

Some IHS facilities waited longer to see federal funding. As of April 7, the Rocky Boy Health Center in Box Elder had yet to receive any aid, but it was communicating with IHS intermittently.

“IHS calls every other week, so it can be kind of hard to get direction on what to do,” said Rocky Boy Health Center chief operating officer Tessie LaMere. “It is still up in the air how IHS is going to disperse the money.”

But LaMere also insisted that IHS had supported Rocky Boy by distributing medical supplies and personal protective equipment coming from the National Supply Service Center.

“They’ve been very helpful with supplies,” LaMere said. “I’m not going to criticize IHS.”

Not all tribal members are as forgiving.

“They will not be equipped to deal with this,” Main said. “If people test positive for the virus and start having problems, they’re better off going somewhere off the reservation for treatment.”

-William Main

Cause for Concern

As a resident of the Fort Belknap reservation and a mother who raised three tribally enrolled children, Michelle Ereaux has a troubled past with IHS.

When she was in law school at the University of Arizona, her professor asked her why she wanted to be a lawyer, her response was short.

“Because I want to go home and sue IHS,” she said.

Her troubles stem from a long history of unsupported needs. It’s not just the time IHS wouldn’t pay for her son to get 10 stitches in Billings, or the time he had a 104-degree fever and they told her to drive him to the nearest IHS facility, over 150 miles away. It’s the culmination of all the times IHS wasn’t reliable when Ereaux and her family needed them most.

Now, in the onslaught of COVID-19, she said she has no confidence in IHS to be a reliable source of care or support for Montana’s Indian Country. And as funding allocation continues to delay and the first confirmed cases hit Montana’s reservations, Ereaux’s lack of confidence in IHS is shared by many; perhaps most by her cousin’s husband.

William Main, a Fort Belknap resident, lost his wife due to what he believes was IHS negligence. Main’s wife, Dianna Longknife Main, died from non-alcoholic liver disease after receiving a liver transplant at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix. Before the transplant, the doctors at Mayo Clinic told the couple that her transplant could have been avoided entirely if the IHS facility doctor had stopped prescribing her a pre-diabetic drug when she was diagnosed with liver disease two years earlier.

After Main’s transplant, the couple was forced to disregard doctors’ recommendations for post-op care because of inadequate IHS funding. Main said IHS wouldn’t pay for her medication to be filled at the Mayo Clinic, and the IHS in Phoenix wouldn’t fill her prescription unless she saw one of their physicians.

Instead of being in a controlled treatment center for people with compromised immune systems, Main was sitting in waiting rooms with other sick people waiting for an appointment for a drug that she was already prescribed. She died a few months later.

Main believes his wife’s death can be blamed on multiple missteps taken by IHS, and that inadequate funding is the main problem. If IHS was able to finance hospitals in rural communities like Fort Belknap better, they would have been able to provide better care.

Stories about IHS negligence or inadequate care are not uncommon. However, in the midst of a pandemic, these prior experiences of disappointment are leaving people who depend on IHS for their healthcare to question why they would have faith in the program now.

Just four months after his wife’s death, Main said he has no confidence in IHS to respond appropriately to COVID-19.

“They will not be equipped to deal with this,” Main said. “If people test positive for the virus and start having problems, they’re better off going somewhere off the reservation for treatment.”

All Things Considered

Some tribal leaders feel that despite the mounting concerns, IHS is doing the best it can under the current circumstances.

“When you look at the scenario in New York, even they aren’t capable of handling [coronavirus] with their infrastructure,” said Crow Tribe Chairman Alvin Not Afraid, Jr. in a live community update on Facebook. “[That is] a wakeup call. I believe IHS is doing everything in their power to accommodate what may come.”

Not Afraid, Jr. said the hospital on the Crow Agency has room for 20 patients, and the community of tribal members and non-members has around 8,000 people. He believes IHS is aware of their limitations, just like the Crow Agency is.

“We know our healthcare system and space is limited,” Crow Tribe Vice Chairman Carlson Goes Ahead said.

The same limitations seem to be present everywhere. According to Rob McDonald, communications director for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes on the Flathead reservation, the tribe’s relationship with IHS has included continued support, but there have been unmet needs and a strain on CSKT Tribal Health resources.

“The system and people within it are tired,” McDonald said. “[They are] being asked to do more than ever.”

Waiting for Answers

If the system is tired, it fell asleep when Jestin Dupree needed it most. Dupree, a member of the Fort Peck Tribal Executive Board, said in March he waited almost three weeks for results from a screening he sought out at an IHS facility after worrying about a cough.

He self-isolated while awaiting answers, as instructed by healthcare providers. The days turned into weeks, and communication from the facility was limited. Dupree tried to keep his situation private, hoping to suppress suspicion and fear amongst colleagues he had interacted with until he had clear answers. “I stopped showing up to meetings, and people started asking questions,” Dupree said. “Everyone was looking at me like I was a bug.”

It took 20 days, many phone calls and multiple prescriptions before the facility confirmed Dupree did not have coronavirus. The breath of relief was short, punctuated by the pressure of reassuring everyone of his healthy status. But the frustration lingered.

“There were so many unknowns,” Dupree said. “A non-tribal member isn’t going through what I’m going through. The process is not fair.”

What Money Can’t Buy

As more cases are confirmed in Indian Country, the strain on the communities transcends financial shortcomings and lacking supplies. Community health specialist Alma Knows His Gun-McCormick stresses the increased importance of closeness and culture in the Crow Agency.

“We are close-knit,” McCormick said. “The way we relate to one another when we see each other in public, we want to spend time and talk. We want to give hugs. We relate to one another in that manner. For us to stay six feet away has been very challenging.”

Messengers for Health is a non-profit organization dedicated to improving community health on the Crow reservation. McCormick, the executive director, has worked hard to impress the importance of social distancing on her audiences, especially since the Crow Agency is home to a lot of people with pre-existing health conditions like diabetes.

“Someone who already has a compromised immune system, which is what diabetes does, [makes them] more susceptible,” McCormick said. “And just because someone is diabetic does not mean they understand their health condition.”

Messengers for Health provides one-on-one consultations for people dealing with chronic illnesses as a way to help them better understand their conditions and lead healthier and safer lives. This type of support became more complicated when COVID-19 was introduced to the equation.

McCormick took to the Messengers for Health Facebook page, posting an audio file of her speaking in Crow language, explaining the importance of social distancing and clean hygiene. She is hopeful that the power of her community’s language will motivate people to really listen to the message’s words.

“Speaking in the English language and then speaking in my own Crow language, I gave words of encouragement and was encouraging people to follow these precautions, and to know that this is very serious,” McCormick said. “That’s the most powerful way to relay a message, to hear someone speaking these words in our language.”

She feels IHS has done a good job handling COVID-19, but is also aware of her community’s general distrust in the system. She explained that many Crow members choose to seek care at the Big horn Valley Health Center as opposed to the IHS facilities on the reservation. Access to a larger community hospital could be the difference between life and death for severely at-risk COVID-19 patients in need of ventilators or special care.

Despite the financial strain, community pressures and medical stress of COVID-19, seemingly increasing every day, McCormick’s prescription for those facing the future comes free of charge.

“We’ve taken some things for granted,” McCormick said. “It’s making us stop, think and count our blessings. We have to slow down.”

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE:

PREVIOUS:

Borders Against Infection

NEXT: