Banking On Snow

Niitsitapi use old tools for worsening winds

Story by Griffen Smith, Photos by Jack Condon

The wind that blows across the Blackfeet Indian Reservation is so severe it’s iconic. During the winters, it tends to blow snow clearly off the land. While the mountains framed the western horizon with blue and gray ice-capped peaks, most of the frozen ground in the grasslands below was bare of snow — void of the moisture it could have absorbed later in the year.

For instance, on a late March day, the landscape across the barren sections of the land displayed a winter phenomenon. The frozen ground laid bare, brown from earth and grass.

However, snow still noticeably clung to the eastern sides of hills and low-lying streams, in the shadows and hidden from the blowing winds. The snow followed the natural topography of the rolling plains.

As the winds, fueled in part by warming temperatures, grow stronger, tribal members are trying to emulate the natural shelters to keep the snow from blowing away.

“Water is life, and we have the best water in the world,” said Wyett Wippert, a hydrology student at Blackfeet Community College. “We just need to work to keep it here.”

Wippert paced the perimeter of a 10-foot-wide boulder resting on a creek bed in a field of yellow bunchgrass. As a member of the Niitsitapi tribe, he recalled a years-long span when the field east of Browning had been dry after strong winds and early warm days ate the snow away.

Tribal climate adaptation specialists have erected snow fences to help retain moisture in fragile wetland ecosystems on the reservation.

Last fall, Wippert and the Blackfeet Environmental Office built two snow fences along the former wetland. The goal: test fence designs that would retain the moisture longer into the year. It seemed to work like the low-lying hills on the plains, while the rest of the ground was uncovered, the two fences built before winter accumulated a 30-foot-wide circle of snow

Winter weather is a guarantee for roughly six months on the Blackfeet reservation, depositing roughly 80 inches of snow annually. However, its sensitive water cycles are being increasingly disrupted by

climate change. Wind speeds have been rising and a healthy snowpack has not been guaranteed, causing widespread drought and an increase in wildfires.

As spring returns to the Blackfeet Nation, Wippert and the team are looking to protect sensitive ecosystems from worsening winds and drier summers. Projects have whirled about the reservation, leading to beaver mimicry dams, student snow fence designs and buffalo reintroductions.

“We created an ecosystem here,” Blackfeet Climate Change Coordinator Termaine Edmo said as she watched the water ripple from the wind. “Three years from now, this place will have green grass and wildlife.”

But some on the reservation are already feeling the impacts of climate change. Residents have recently lived through out-of-season fires, drought, merciless winters and extreme wind events. With residents concerned for more hardships living off the land, the environmental office hopes snow fences could be the spark needed to retain its wetlands.

***

Browning and most towns along the Rocky Mountain Front are known for the wind. The Great Falls National Weather Service branch previously listed its data station on the reservation near East Glacier as Montana’s windiest location.

Tracking wind trends are limited, especially in Browning, where there is about 15 years of weather station data, according to Kyle Bocinsky, director of climate extension at the Montana Climate Office.

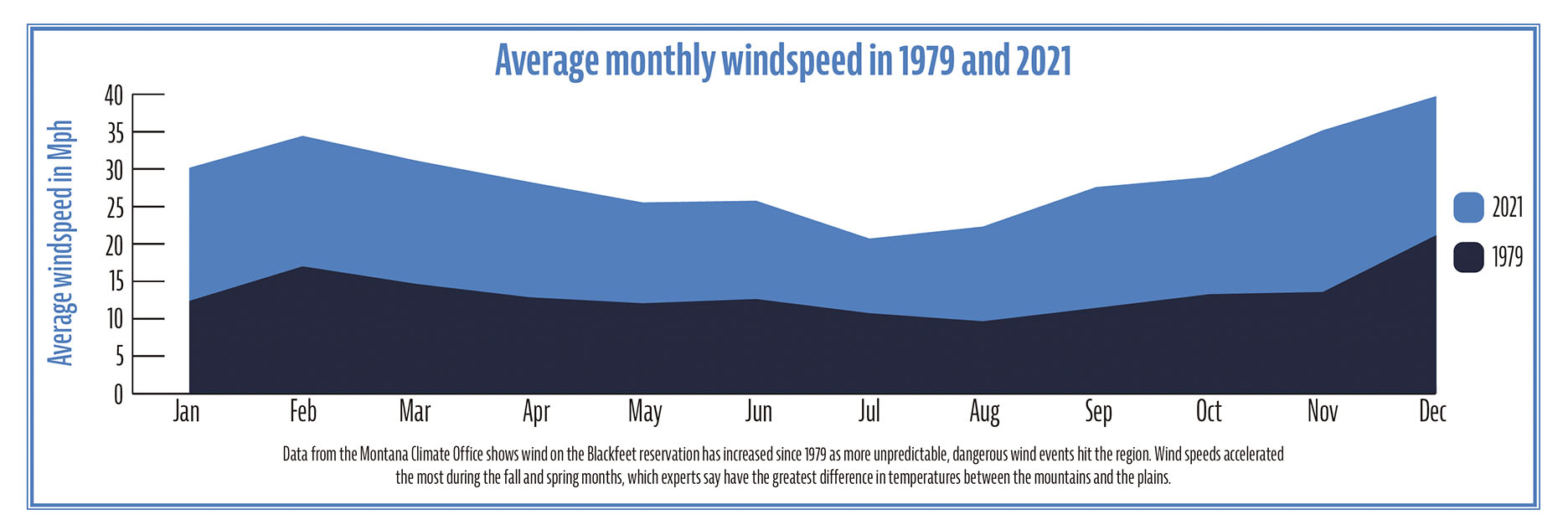

Despite a lack of pinpoint data, Bocinsky calculated a wind trend by using daily weather forecast maps for the past 43 years. What he found was a clear and concerning trend.

“What we see is exactly what people are reporting, that we’ve had a really measurable market increase in wind speed during many of the months of the year,” Bocinsky said.

Spurred on by the winter chinook winds, the region’s wind season happens during the winter. Wind-carved snowbanks could get dozens of feet tall with ease. Some of that snow, however, gets swept off the landscape and can stay suspended long enough in the atmosphere to warm into a gas.

Sublimation, the direct transfer of a solid object to a gas, happens when snow is held in the atmosphere long enough for the sun’s heat energy to transform the particles into a gas.

“It feels like the snow is melting, but actually the snow is evaporating,” Bocinsky said. “You get snow disappearing faster. You do get more blowing snow, although I don’t know if you would have the situation of snow just going away.”

A 2009 study from Canada’s Water and Climate Impacts Research Centre found high-elevation mountain ranges in western Canada lost 1-4% of its snow-pack from sublimation alone.

Researchers said that number increased in open spaces, and faster winds would likely take more snow off of the ground. Bocincky’s data found the most accelerated wind speeds happened during the transition from winter and summer, significantly increasing in September through November and January through March.

The Blackfeet reservation’s average wind speed in March increased from 14 mph in 1979 to 18 mph in 2022. November’s average speed increased from 16 mph in 1979 to 19 mph in 2022. Bocinsky attributed the higher winds to the growing temperature differences, known as a gradient, between the mountains and the plains.

“Temperature gradients is one of the main things that drives wind,” Bocinsky said. Specifically, if there is a really hot area near a cold area, that creates wind blowing in one direction, Bocinsky said. These temperature conditions are common in mountain borders. “So people on the Front Range feel the wind pretty constantly because of that temperature gradient and that elevation gradient.”

Many experts predict the extreme winds will become more common over time, according to the Trottier Institute for Sustainability in Engineering and Design at McGill University in Montreal, Canada.

***

Snow breaks or fences have been primarily used to control snow banks. The barriers are often placed in single file rows, facing toward the wind (Browning’s wind comes from the west) or on the spine of ridgelines to moderate the height of the snow. Without it, snow can fill divots or envelope roads and rail lines.

Wind breaks in the form of fences or trees are common at remote homes across the reservation. The fences have also become valuable assets for saving water and protecting livestock.

Joe Kipp, director of the Blackfeet Nation Stockgrowers Association, recalled the unpredictability of snow each year. In 2018, an eight-foot snowstorm blanketed the reservation, forcing ranchers into a scramble to secure their livestock amid giant snowdrifts and low visibility.

Kipp, who has ranched near the Rocky Mountain Front for 40 years, hastily built snow fences to prevent his cattle from getting buried in the banks. The strong winds and whiteout conditions could wreak havoc on livestock, and make any travel hazardous.

“We were lucky, we only lost a couple calves,” Kipp said. “Those who are getting into the industry now are really struggling. Some couldn’t get to their cattle at all.”

Snow lingers in the mountains of the Rocky Mountain Front, but the plains beneath have been stripped of snow by intensifying winds.

Other years, Kipp said the ground on the plains has been bare in late winter. The snow that does fall gets drained by rain-on-snow events and sublimation.

The Browning-based Chief Mountain Hotshots fire crew warned of the impacts from the powerful winds

that whip the primarily grassland habitat. Jovon Fisher, the Chief Mountain interim fire chief, said the winds have picked up the snow in huge gusts, making wildfires easy to ignite and spread.

“It is always windy up here, but we are having these ‘wind events’ of dangerous speeds that will flip over trailers and knock over power lines,” Fisher said. “I know it’s been a change, and it’s been changing rapidly.”

It is a worst-case scenario — a knocked over powerline that ignites a grass fire — that has already happened twice on the same plot of land in 2021, first in March, followed by a burn in early December.

Fisher, who also volunteers for the local fire department, picked up the phone in the middle of the night Dec. 2. A Glacier Electric Cooperative powerline fell at 3:30 a.m; dry ground sparked immediately. The wind, measured between 80-90 mph gusts, fanned the flames.

“That’s over by my cousin’s land,” Fisher said. “I got straight into my car, and by that point my whole team was on their way too.”

But the damage had already been done. Rick Whitford, a rancher who’s property the fire spread into, watched as the blaze took out his hay supply and horse barn. The fire, which was over by the daytime, sparked in the same area as the March 2021 burn, scorching the same weakened grasslands.

***

Unpredictable weather has become a centerpiece of the Blackfeet Nation’s Climate Change Adaptation Plan, which was approved by the Blackfeet Business Council in 2018. The action plan details climate observations made by tribal members, and the future effects that will impact the land.

Climate change work has been in progress on the Blackfeet since 2017, according to Gerald Wagner, who has led the Blackfeet Environmental Office for 27 years. Wagner has watched environmental work expand from a few essential programs to developing more partnerships with the Environmental Protection Agency and the Center for Large Landscape Conservation.

“We have to work together, there is no one person or group that can do this,” Wagner said. “We’ve got to all be in this together to slow it down. You know, it’s already here. We ain’t gonna prevent it.”

1. A Browning High School student weaves willows into a snow fence during an agricultural class. 2. In summer 2021, Tyrel Fenner and Browning High School students built a snow fence using willow branches gathered by community members.

Now, Wagner and his team are conducting studies on climate change’s impact on human health, while leading Earth Day celebrations to engage tribal members to join the sustainability movement.

The plan also lists the possible responses by the tribe, and the significance of the land the Blackfeet have watched over for thousands of years.

“Observing weather patterns and changes in those patterns has been a part of Niitsitapiiksi, The Real or The Original People, existence since breath was first breathed into our lungs by Creator,” the plan reads. “Within our homelands, we were the first climate scientists or climatologists … the first stewards of the land and water and all that lived on the land, flew in the air, or lived in or around the water.”

Despite the robust work, Wagner said the effects of climate change are here. Wagner attested to a changing spring season. There are an increased number of warmer days in the spring dissipating the snowpack and expanding the growing season.

A majority of the department’s funding relies on grants, many long-term. The office has gotten hundreds of thousands of dollars from federal agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency, but recently lost out on other grants that would have expanded their study on cultural effects from climate change.

The department, however, has embedded itself into decisions on ecosystems from other tribal departments like forestry or agriculture.

Much of the Blackfeet economy comes from farming and ranching, which uses 60% of the land on the reservation, the number one economic driver where many work to break even. The plan said the risk of losing healthy grasslands is a high priority.

***

Edmo, the climate change coordinator, has been responding to environmental problems in a hands-on approach since 2018, when the adaptation plan was introduced.

She was the first employee hired for the climate office, and often the only climate employee when the grants don’t flow in. A member of both the Niitsitapi and Shoshone-Bannock tribes, Edmo has worked to use her traditional upbringing into the ecological restoration work she leads.

Blackfeet Climate Change Coordinator Termaine Edmo began her environmental career as a “Climate Warrior” with a Blackfeet internship program for tribal youth working to solve climate change problems.

“I’d like to think of my father, who is a little hesitant to mainstream climate change, but understands our traditional practices,” Edmo said. “That’s how we can do our outreach.”

Divided up into different sections like wildlife and water, Edmo partners with agencies across the reservation. She has so far focused on the nation’s wetlands, installing beaver mimicry dams along the Willow Creek watershed to keep water in riparian areas.

Edmo also teaches the traditional way of harvesting bison, using a herd the tribe established in 2022. The day after a harvest, her arms hung sore from taking apart the bison. The next day she is in her office writing grants for potential projects.

The environmental office has taken notice of the wind problem. In fall 2021, the climate office partnered with the Blackfeet High School and Blackfeet Community College to design and build wooden snow fences. Just outside of Browning High School, there are three types of snow fence prototypes framed with two-by-four wooden planks.

Tyrel Fenner, a tribal climate adaptation specialist, carefully weaved willow branches into the third snow fence. Fenner picked up the trees from a family friend’s property.

Recently completed, the thicket of the branches secured the windblock into place, a practice Fenner attributed to Traditional Ecological Knowledge — using tribal practices for conservation work.

“It’s great because we can use materials right here in our backyard,” Fenner said as a group of high school students walked over to help fill in the willow fence.

Fenner, who works for the non-profit Piikani Lodge Health Institute, has teamed up with the environmental office to offer climate change education to high schoolers and the college students.

Because the wind always blows from the west, the snow protected by the fence is always to the east. The high school students helped build and monitor the snow levels with steel posts lined up behind the fence, known as the fetch. When the students aren’t around, Fenner recruits his nephews to come help him.

As Fenner worked with the high schoolers to weave willows, he said the snow fences would be best for small wetland ecosystems.

“We call them pothole ponds, because they have no inlet or outlet,” Fenner said. “Lots of them can’t keep any water into the summer, and that really starts to affect the animals looking for a place to drink.”

***

East of the tribal college, the two fences on the edge of a wetland collected enough snow to hold water in the shallow channels that criss-cross the Willow Creek watershed. The barriers were not moved over winter, and the snow naturally hydrated the section of creek.

Wippert, the student hydrologist, couldn’t help but crack a smile talking about his project.

“It felt really cool to see it in action, we’ve been working on them for months,” he said. “You can do this anywhere, bringing the water back.”

A snow drift shelters from the wind behind a snow fence on a pasture along Highway 89 south of Browning, Montana.

Wippert, who grew up in Browning, first went to Missoula College, earning a degree in diesel mechanics. He came back to his hometown for work, but work was tight because of the pandemic.

He eventually got a job at the Blackfeet Solid Waste Management as a garbage driver during COVID. But he knew there was something else out there for him. As an outdoorsman, Wippert said he wanted to work with the natural world around him.

He enrolled in hydrology school and found his new passion through the Native Science Field Center, which works out of the tribal college and gives informal ecological education to children in kindergarten all the way through high school.

As a fellow at the center, Wippert helps manage the snow fences and helps run programs for young people. Wippert doesn’t know where he’s going to go once he graduates in May, but he plans to improve water systems in Montana.

While the fences worked, there are still setbacks to having them mass-produced. The fully-wooden wind fences made by the field center cost roughly $2,000 to build, partially from the sharp increase in wood prices. The machine plastic option ran for a few hundred dollars cheaper, but is less durable over time. The willows are a cheap option, but require more time to weave into place.

No matter the final design, Edmo’s goal is to give out the schematics to members around the reservation, on top of adding more in places the team wants to restore. Since fences become obsolete in the summer, a mobile version — allowing people to move the fence to different spots throughout the year — would be ideal, she said.

Going into the summer, the office looks to hold two environment celebrations in May to continue to make adaptations to their ecosystems when they come. Edmo said an important point in the plan is that the office can make changes as needed. She said no matter what comes next, she said the climate office, and the Niitsitapi nation, will be there.

“It is daunting work,” Edmo said. “We know that there is suffering in our environment, but we are adapting, like our tribe has for thousands of years. We are here to keep going.”

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE:

Previous