A complex white picket fence

The ‘red tape’ surrounding Indigenous homeownership on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation worsens under Trump’s administration

Story by Emily Messer. Photos by Taylor Decker.

After 40 years living in Seattle, Amber McEvers White wanted to move home to the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. Her mother, Wilma North Peigan, an elder, was struggling to get around in the tough winters.

To prepare for this life change, McEvers White lined up everything she thought she needed. The land was purchased. She had, in her hands, construction plans for a home inspired by the Yellowstone TV show on a budget; three bedrooms, two levels.

Six years passed, and nothing moved forward.

McEvers White had tried to find anything. She applied first for a lease site, buying land and then looking for other options. She made a flight home, more than 20 phone calls and sent several email messages. But in March of 2023, the builder was ready to cancel the deal.

“It’s just a frustrating process. I felt like I couldn’t even get anything on my own reservation,” McEvers White said.

Homeownership has always been complicated on tribal reservations. Even removing the economic factors like high unemployment on many reservations, the unique relationship that tribes have with the federal government make landownership technically impossible, removing any hope of building equity in a home.

In fact, the American Dream of a white picket fence is 15% less likely for American Indians compared to White Americans according to a 2022 survey by NeighborWorks America, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit that advances opportunities for affordable homes in every state. Now, with the reelection of President Donald Trump, the red tape is thicker, the costs are higher and the dream is that much farther for many tribal citizens.

“The Bureau of Indian Affairs just had a bunch of agency offices shut down. So that’s going to impact the ability for homeownership in a big way,” Robert Crawford, a contractor for the BIA, said. “[The BIA] haven’t really released any of that information yet. [Housing and Urban Development] is definitely being affected, but I don’t know to what extent.”

The entire state of Montana is facing a severe housing crisis with skyrocketing prices and a limited housing stock, making the state the least affordable in the U.S. according to the National Association of Realtors.

In Browning, where McEvers White was hoping to build her home, the path to ownership is just one option on a reservation with nearly 10,000 people. There are run-down homes, low rent apartments and a minimal private rental market.

For McEvers White, moving home was a logical option to take care of her mom and live closer to her family after living in the Seattle area for the last 40 years. She took the first steps into homeownership in 2019.

“I lived away for a number of years and we saved a lot of money to do this because we knew we didn’t want to retire in Washington,” McEvers White said. “People that don’t have the money, I don’t even know how they go about getting what they want or getting what they need.”

In the end, McEvers White purchased a home on the Flathead reservation just to be closer to her family and back in Montana.

On the Blackfeet reservation there are about 6,000 homes that were built in the 1970s and they are considered “hands off,” meaning the tribe has no control over them. Blackfeet Housing Authority, separately from these homes, maintains about 400 low-rent apartments and there are currently 200 people on the waitlist. The private rental housing market on the reservation is almost non-existent. That leaves the Blackfeet Housing Authority unable to provide enough housing.

Crawford, a real estate specialist and Blackfeet citizen said there are 3,000 to 3,500 people who own homes but there is a current need for about 3,000 more homes.

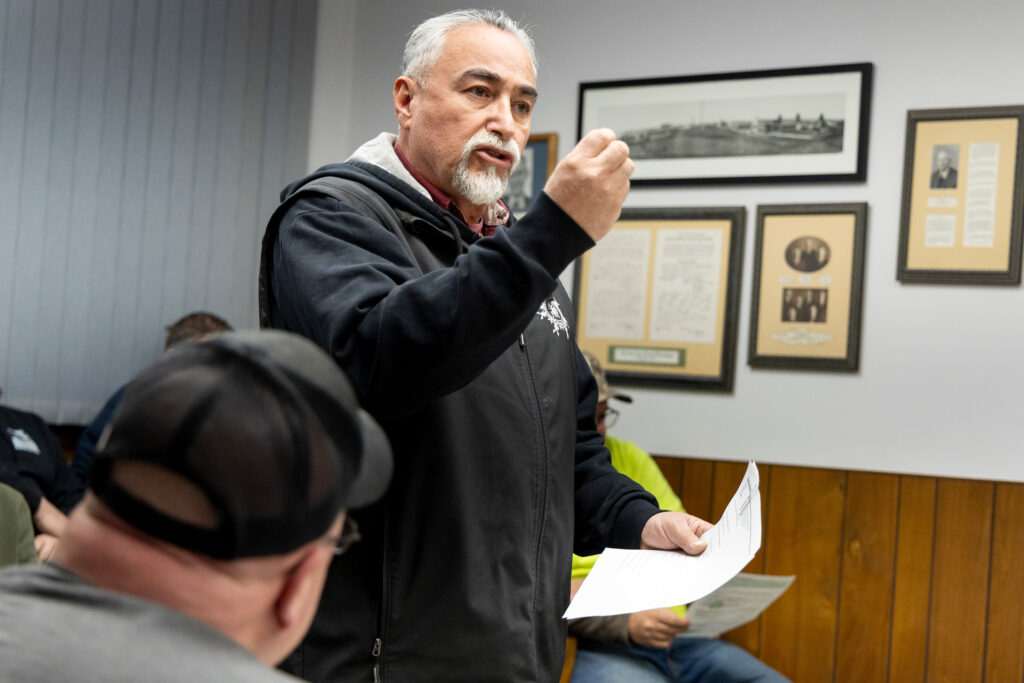

This has led Crawford to implement the Pathways Home: A Native Homeownership Guide, an eight-hour course developed by the National American Indian Housing Council to educate tribal citizens on leasing, purchasing and owning homes.

Counselors in the program are certified and paid through the U.S. Department of Urban Development. Crawford doesn’t have the resources to teach the course in person anymore and has streamlined the process by creating an online class.

However, when Crawford worked for Blackfeet Housing and the Tribal Land Department, he was limited to working with low-income tribal citizens, many of whom weren’t ready for homeownership. But once he helped them build income and credit scores, Blackfeet Housing would kick them out of low rent housing because they wouldn’t then qualify for the program.

“I didn’t have an assistant or anybody to help me out,” Crawford said. “I fell too far behind on my other work, so we put everything online.”

Crawford said there are two significant roadblocks to homeownership: the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the lack of education. He said he spends about 90% of his time just putting out information.

“They just don’t know where to look. You can’t know what you don’t know,” he said. “It’s not something people think about every day, but when they do think about it, it becomes the most important thing.”

In 1981 the median age of a first-time home buyer was 29 years old. According to the National Association of Realtors it has risen to 38 years old in 2024.

Top: Blackfeet citizen Wilma North Peigan says that it’s a family tradition to live in East Glacier. North Peigan lives with her daughter Amber McEvers White on the Flathead reservation so that North Peigan can be cared for. Bottom: Real estate specialist Robert Crawford educates people on how to become a homeowner on the Blackfeet reservation. Crawford teaches a virtual class required by the tribe for those that are becoming homeowners.

Obtaining the trust land

There are four common types of land that can be used for homeownership on reservations. Each of these have technical differences, though they each require heavy bureaucracy.

- Allotment or allotted trust: This is the oldest form of land that comes from the Dawes Act of 1887, which gave the head of household an allotted piece of acreage that is held in trust by the U.S. government. The tribe has no control or say over the operations on the land unless it is illegal activity.

- Patent fee: Taxable land that can be owned by anyone, tribal or not tribal citizen. The land is not held in trust and the landowner can sell or gift the land without BIA approval.

- Tribal fee: Land the tribe purchased from an owner who has defaulted on a mortgage or property taxes. The tribe often offers these plots as homesite leases and requires additional permissions for certain activities such as commercial or agricultural uses.

- Tribal trust: Tribally owned land that can be leased to tribal or non-tribal citizens. The tribe has full control over this land to mine, drill or keep as wild. However, when it is a lease, the leaseholder does not own anything below the surface.

During her six-year effort to build a home, McEvers White applied for a homesite lease – a 2.5 acre lot – through the tribal Land Department. Such lots are available to Blackfeet citizens.

Her first attempt was to obtain patent fee land. McEvers White, her daughter and her brother all applied for homesite leases next to each other and just a 10-minute drive from her mom’s house in East Glacier.

These homesite leases typically last 25 years or for as long as the individual’s mortgage. The lease costs $120 a year and requires a council resolution. The resolution is a timely process according to Gracie Show, a real estate specialist at the Blackfeet Tribal Land Department who previously managed the homesite leases.

Each council member must approve the lease site as well as the minutes from the meeting in which the lease was presented before the resolution is final. But not every lease is granted.The tribe can decline it due to the location if it splits up agriculture land. McEvers White remembers her lease being granted quickly.

The resolution is then sent to the BIA for approval. The agency may request additional information or require surveys which can cost upwards of $3,000. These BIA checkboxes to obtain a Title Status Report are a “hassle,” Show said, which is why the Land Department began to survey land and create subdivisions of ready-to-develop lots in order to simplify the process.

McEvers White applied for her lease in August of 2019 and said the tribe approved it right away, but the process stalled waiting for the BIA. While at home in Seattle, McEvers White’s phone dinged with a confused text from her brother. Attached to the message was the BIA’s paperwork stating her application was incomplete.

McEvers White was given 30 days to clarify her paperwork. She said she reached out to the land department to correct her address and follow up. But she was left with no response. It wasn’t until a year later that the BIA called and asked for the documents.

“I did all that and I paid for it. And here’s my check,” she remembers telling them on the phone. “I got so frustrated with the process. I didn’t feel like anyone knew what they were doing.”

Moving forward, the process doesn’t seem to be getting any easier. The Department of Government Efficiency announced plans to close 25 BIA offices in 2025, about 27% of its locations nationwide. This includes two Montana locations.

“The impact on Bureau of Indian Affairs offices will be especially devastating. These offices are already underfunded, understaffed, and stretched beyond capacity, struggling to meet the needs of tribal communities who face systemic barriers to federal resources,” stated Jared Huffman, a U.S. House Natural Resource Committee ranking member in a press release.

However, the BIA has a notorious reputation for its bureaucratic culture even without considering potential downsizing.

The BIA office on the Blackfeet reservation refused an interview and directed all communication through the BIA media contact. After five emails, the media contact did not provide any information.

McEvers White never received approval from the BIA and when she tried to make the yearly payment, the agency declined it. She felt discouraged and decided to find another path to homeownership. McEvers White spent the summer of 2022 at her mom’s house and during those three months she was asking anyone if they were selling their land and making offers. Finally, a lot became available at a price higher than her range. She made an offer.

McEvers White’s offer was accepted in October of 2022 for the 41-acre lot and she was finally feeling hopeful that she could start the building process.

The total Amber McEvers White spend on trying to move home to Blackfeet was $300,000

$260,000 was spent to purchase the 41 acres.

$15,000 was spent on house plans.

$4,000 was spent on fencing repairs for the 41 acres.

$1,000 was spent on surveys for the homesite lease.

The right of way

The next step for McEvers White was to obtain building plans and find a contractor. All contractors who build on the Blackfeet reservation must be vetted by the Tribal Employment Rights Organization Office. McEvers White spent $15,000 on building plans.

Then there was the water right of ways. It should have been a simple step. McEvers White would have to go through a homesite lease. She was confident the tribe would grant the request.

What McEvers White soon discovered was that a neighboring lease holder held the right of way to the water that ran under the plot. The dispute intensified quickly and McEvers White decided to abandon the lease.

She also abandoned her dream of building on her reservation.

“I was so determined because we had a lot riding on it. I just did what I had to; jump through all the hoops I had to,” she said. “Only to find out I needed permission from the leaseholder and not the tribe.”

After months of fighting right of way rights and the overall build not moving forward, the contractor grew frustrated and wanted to give up on her project.

There was a condemned house near her mom’s that had been abandoned for at least five years. While it needed a “new everything” it was a consideration, but at another cost.

“You want to be with your tribe and your family,” McEvers White said.

But there was still no home, and now no pending home. McEvers White, 58, and her husband Stan White, 63, were ready to move home and retire. Wilma North Peigan, Amber’s mom, said their family has lived in the East Glacier area for generations and that’s why they want to continue living there.

“I was really trying to make it work and I just couldn’t and I just had to let it go,” she said. “It was a lot of energy and a lot of time away from my husband to make sure our future was where we wanted to be and that’s where he wanted to be.”

After spending about $300,000 on attempting homeownership on her reservation, it was time to pivot. McEvers White decided to buy a house in Polson, on the Flathead reservation, a reservation with houses for sale without jumping through the loopholes.

No rentals in site

There is an overall housing shortage throughout Montana that seems to be seeping into tribal communities. Julius ManyGuns-Pinkerton, a third-grade teacher at Browning Public Schools moved back to the reservation in June 2024. She and her husband Steven made too much money to live in Blackfeet Housing low rent apartments.

The family now lives in ManyGuns-Pinkerton’s aunt’s house. Walking in the small three-bedroom house, her oldest sleeps on the living room couch while her 4- and 2-year-old children share a bedroom with her and her husband. There are seven people living in the house in total. Overcrowding in homes on the Blackfeet reservation is a common problem due to the lack of housing availability.

“There’s so many people hurting for homes,” ManyGuns-Pinkerton said. “And then you see the people that did go out and then come back, like myself, and we’re still struggling. We make too much money to live here.”

ManyGuns-Pinkerton applied for a homesite lease but has not received a definite answer. While she tried to talk to lenders, she struggles to make it work.

“It’s really hard to think that here I am a teacher, homeless with my children and still living with family,” she said.

There are only a handful of lenders working on the reservation due to the extensive lending requirements imposed by the BIA. Add to that the bureaucracy of obtaining land. Crawford said this has made for a 7-8% success rate to homeownership because every third person who tries, gives up.

“It is just the sheer amount of red tape that is put there with good intentions,” Crawford said. “They say, ‘The road to hell is paved with good intentions.’ But it really does harm tribal members. It’s meant to protect them, but it really causes these wide-ranging problems.”

ManyGuns-Pinkerton is considering purchasing a model home which would require a $10,000 down payment to secure the home, a cost ManyGuns-Pinkerton is willing to take to get her kids into their own home on a homesite lease.

With the cost of building being so timely and difficult with the tribe, Crawford has been passionate about getting model and 3D printed homes on the reservation. The cost of building a home has increased by 34% in the last five years according to the National Association of Home Builders, but now with increased tariffs the Wells Fargo and the Association’s survey is estimating a $9,200 building cost increase per home.

Lending on reservation land

The NACDC Financial Services was established in 2010 by Elouise Cobell, a well-known Blackfeet citizen who sued the federal government over holding Native land in trust. NACDC provides four different types of home loans along with guidance through the process.

“We aren’t a bank, we have more time to walk people through the process,” Patty Gobert, the executive loan administrator at NACDC Financial Services said.

While the process is different through the tribe depending on the type of loan, financial services is a community centered organization and builds loans based on the community’s need.

This isn’t the only tribal lender, there are three “big” Native lenders in Montana, according to Crawford. Each have their own requirements and dollar limit.

“Getting a loan on an Indian reservation is pulling teeth. It is incredibly, incredibly hard. The land never truly belongs to us, but it belongs to us,” Crawford said. “I won’t say it’s because of the lenders. I’d say the lenders have bent over backwards.”

Lockley Bremner, a Blackfeet descendant, went through the pathways course in 2004 and thought it would be a “slam dunk” to build a home. While Bremner quickly obtained a land plot, he could not find a lender to finance the construction.

“One of the things the bank said was that they don’t do long-term trust property. Luckily we were able to find a piece of land that wasn’t in trust. It was a lot of hard work,” Bremner said.

Bremner, his wife and four kids were able to purchase a 50-by-120-foot lot of reservation fee land from his grandma at a “family deal” for $1,000, which was a third of the market value. This helped Bremner avoid issues surrounding trust land. He and his wife headed to the bank with perfect credit.

“We got a letter back from SunTrust Mortgage, that said there’s no market for home loans on reservation,” Bremmner said. “We were like ‘What?’ Just shocked that we were denied the mortgage or loan to build.”

But Bremner, who had a plan with his wife Brandy to build a house before they were 30, kept moving forward and found the Native American Bank. They secured an adjustable-rate mortgage which has a five-year fixed interest rate with the option to refinance to a fixed-rate.

“They’re not really the kind of loan you want to get, but it was what we could get. We finally got a loan after a year of trying,” he said.

Bremner started with a high interest rate, which made it hard to “get above water,” he said, this was the only option. However, in 2021, Bremner was able to refinance and take advantage of the HUD 184 loan, a 15-year fixed at a 2.8% interest rate.

But even after finding the right loan, lenders typically require insurance.

Crawford said there are only about four companies that insure homes on tribal lands but if it’s tribal trust, people are left to shop around to find the insurer willing to cover the home.

“It’s confusing if you’re showing an insurance adjuster or an insurance agent and they’re like, ‘What is this? You own the house, but you don’t own the land,’’ Crawford said. “That sounds really risky.

He said sometimes insurers won’t even entertain taking accounts on reservations because they are unfamiliar with tribal lands.

McEvers White is now in Polson, Montana with her mother by her side. While she is still away from her family and tribe, they make a couple yearly trips to the Blackfeet Indian Reservation each year.

Further impacts: Tariffs & the Canadian Border

Now with the re-election of President Donald Trump, many federal changes are coming down. McEvers White along with other tribal citizens are concerned not only about the impact on homeownership but the impact on their economy.

McEvers White said the tariffs are messing with people’s lives and putting a higher strain on the buyer and she sees no purpose in what he is doing “other than to destroy our economy and our way of life.”

Two Blackfeet Nation tribal citizens filed a lawsuit against the federal government on April 4, alleging that the Trump administration’s imposed tariffs on Canada were a violation of the Constitution and treaty rights.

The members, State Sen. Susan Webber, D-Browning and Jonathan St. Goddard, a rancher named the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Secretary and the United States in this suit. St. Goodard crossed the border which is a common practice for members and paid over $300 in tariffs for a new tractor part. He stated in the court document that this cost caused him “financial stress” according to Montana Free Press.

“He’s a negative destructive force. I don’t like what he’s doing and I don’t like how many people are living in stress and fear,” she said. “I don’t see anything positive coming.”

The changes to the BIA, increased tariffs and employee cuts to federal agencies could make the 7-to-8% success rate to homeownership lower and pause applications to homesite leases altogether. Ultimately, increasing the ‘red tape’ to homeownership and hurting the overall Blackfeet Nation economy.

***

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE:

Previous

Standing Alone

Next

A deeper divide