Breaking old ground

Little Shell Chippewa Tribe develop land with federal funds

Story and photos by Griffen Smith.

Gerald Gray walked through the door of a blue warehouse made of metal siding, the inside still fresh from construction. Gray, the chairman of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians, peered into the back freezer taking up a corner of the semi-completed space.

Buffalo meat sat in tightly-sealed wraps in storage boxes.

“People can come in and get the meat now,” Gray said, noting that the soft opening is for members in need. “But soon, we will have rows and rows of food.”

Food for the Little Shell tribe is starting to trickle in. Once the tribe finalizes a deal with the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the next few weeks, the new food sovereignty program will open for its more than 4,500 members.

But the Little Shell will pull off another feat this year, building houses on its own land at the base of Hill 57 — an area deeply connected to the tribe’s members after more than 100 years of living there amid segregation and hostility against Indigenous Montanans.

Enlarge

“We used to live right here,” Gray said as he looked up the slope of the Great Plains hill. “As time goes on, our economic development will start to provide shortfalls in everything. Everything the other tribes here can provide.”

Much of this explosion in growth comes from the Little Shell obtaining federal recognition in 2019. The tribe’s newfound connection with the government has ramped up funding for housing, food, health care and events like powwows.

“It’s like trying to drink out of a fire hose,” said Clarence Sivertsen, the first vice chairman of the tribe. He planned the food program to replace temporary programs the tribe made to feed members during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The new program will give its members a permanent food source. Sivertsen said that although the Little Shell has access to the Great Falls Food Bank, the tribe’s food sovereignty program will allow for more flexibility, more Indigenous food and possibly sending meals to rural members.

It’s been a long way since the Little Shell first built its event space down Stuckey Road in the mid-2000s. By fall, the whole area will be home to dozens of the tribe’s members amid a housing and price crunch in central Montana.

Building the basics

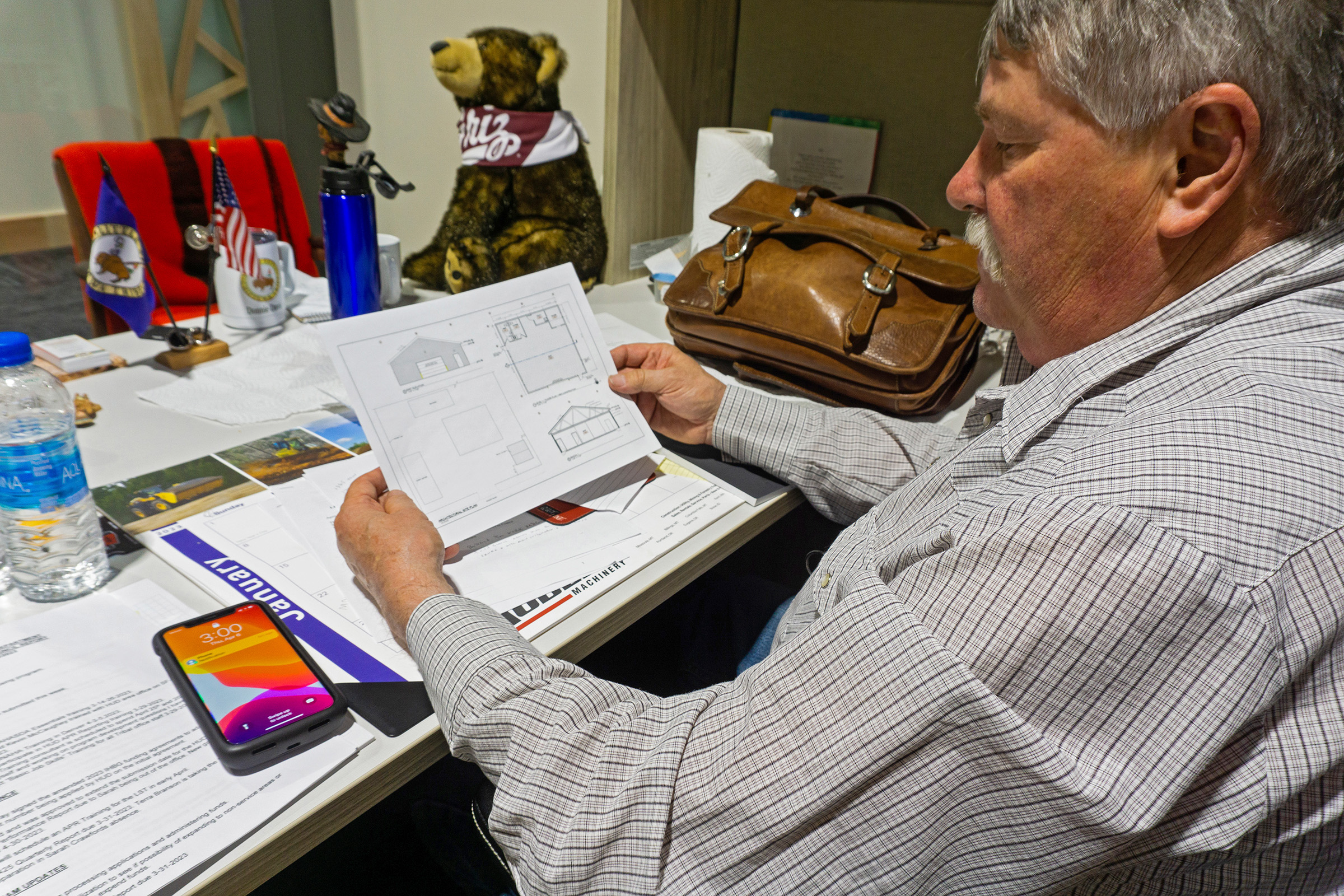

Don Davis, a councilman for the Little Shell tribe, looked through the schematics of all the future projects in his new office on Central Avenue. The tribal headquarters is brand new, with light and colorful travertine from the tribe’s quarry in Gardiner covering the floor and walls.

Davis, the planner for the tiny homes, explained that the Little Shell will get water and sewer systems from the City of Great Falls.

The city commission unanimously approved the annexation of the new 3.67-acre property on Stuckey Road in March. Since the adjacent property has already been connected to the city’s services, the Little Shell connection shouldn’t take long or much money.

Now, with the ground leveled and services ready, Davis will start fabricating small one-and two-bedroom homes that can range from 500 to 800 square feet.

“We’re going to make them nice, because I told the city when we were going through this that we’re not going to build them like Bozeman did,” Davis said, referencing Bozeman’s city-owned tiny homes that do not exceed 300 square feet.

Like Bozeman, however, the tribe’s new housing will be for Little Shell members who are veterans, have disabilities or are currently displaced from housing, Davis said. The money for the project came from the U.S. Housing and Urban Development Department and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Davis said the houses will be transition homes, but added that doesn’t mean the tribe won’t make them nice. Most of his designs show craftsman style homes with front porches. To get one of these homes, a member just has to pay what they can.

“The price will be up on what they can afford,” Davis said. “If they can only afford a couple hundred bucks a month because of their income, that’s all we’ll charge.”

Gray said across the state, housing has appeared as the number one concern for its members.

The average home price in Great Falls is roughly $324,000, up 10% from 2022, according to Realtor.com. The average rent for a one bedroom in the city is around $1,000 a month according to Rent.com.

“Housing prices are going up across the state, and people can’t afford it anymore,” said Gray, who lives in Billings. “It’s our biggest need right now.”

The project will break ground in the next couple of months. By fall, the tribe hopes most of the homes will be ready for move in.

The City of Great Falls was happy to approve the Little Shell project, according to Tom Micuda, the city’s interim planning and community development director. With demand for homes increasing in Montana, Micuda said the city needs to add 450 living units each year to keep pace.

“We have a shortfall, and we need to get into catchup mode,” Micuda said.

With the Little Shell contribution, Gray said the tribe is doing its part in battling high prices to live in the state. But just four years ago the tribe’s council likely could not have made these developments.

Enlarge

Building for the future

The Little Shell tribe is one of the most recent Indigenous groups to get recognition from the federal government. Before the tribe was recognized by Montana in the 1980s, the tribe was made up of displaced bands of people around the northern Great Plains.

The Little Shell, made up of Ojibwe, Chippewa and Métis people, used to live in the Great Lakes region. Colonization of North America pushed the Little Shell farther West.

When the federal government tried to pin the tribe down with the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation near Canada in 1892, Chief Little Shell walked out of the negotiations over the absurdly-low prices the government would pay for their land.

History would show that these negotiations, known as the Ten Cents Treaty, were corrupted through one of the Indian agents on the reservation. Yet, the treaty was signed and the Little Shell suddenly became known as the “landless Indians.”

Many regrouped in Montana, and called the Great Falls area home. But when the white settlers started expanding along the Missouri River, the Little Shell had to relocate up to Hill 57.

“They basically just survived in like a little shantytown,” Gray said.

After getting state recognition in the 1980s, the tribe could start getting support from the government. A small operation started in Great Falls, connecting with its members spread across the state of Montana.

The tribe then set its eyes on federal recognition. In 2019, Sen. Jon Tester amended the National Defense Authorization Act to include recognition for the Little Shell.

To Gray, the period of Hill 57 to federal recognition has been night and day. He already has leased more than 700 acres of farmland around Hill 57 to produce grain for the tribe and constructed a powwow arbor at the top of Hill 57.

As he looked over the hill on a sunny afternoon, he recalled how the next door neighbor was an enrolled member. It’s his people’s place, he said. Beside him, the food sovereignty building stood ready to be one of the center points to the new planned community.

The tribe will soon take its health care center back from Bureau of Indian Affairs control. They plan to purchase a second mobile health care vehicle.

Gray peered far into the distance of old trailers and trails. A new era for the tribe has started, he said, and it will not be slowing down anytime soon.

“I always say ‘just do it,’” Gray said about the new programs. “Every other tribe has a food program or low income housing. It’s time our members have the same opportunities.”

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE: