Critical Luxury

How a pandemic made rural internet a necessity

Story by Sara Diggins, Hannah Welzbacker and Claire Shinner

Zak Hoops is completely in the zone. His feet hit the still-frozen dirt, where he has worn a circle through the snow with his grass dance. The March wind rips across the frozen landscape, ruffling the feathers in his roach and ribbons on his arms and legs as he moves to the beat of the song, played from a phone.

He dances around the frozen circle, perfectly on-beat with the drumming, pausing at times to whirl in place, the bells from his regalia match the beat. Sometimes, the 6 year-old bends down so low the top feathers in his roach nearly brush the ground.

A few feet away, Toma Campbell filmed her son’s performance with her cell phone. She would go on to post the video on one of the many growing online communities for Native Americans to come together while staying socially distant: the Social Distance Powwow Facebook group.

From there, the video went viral, racking up over 33,000 shares on Facebook and grabbing the attention of local TV news outlets. The Social Distance Powwow group grew, gaining members from across the world. A few of them comment on Zak’s video, and Campbell reads him the comments. She said they always put a smile on his face.

Internet fame was the last thing Campbell expected. She said she doesn’t even have in-home Wi-Fi.

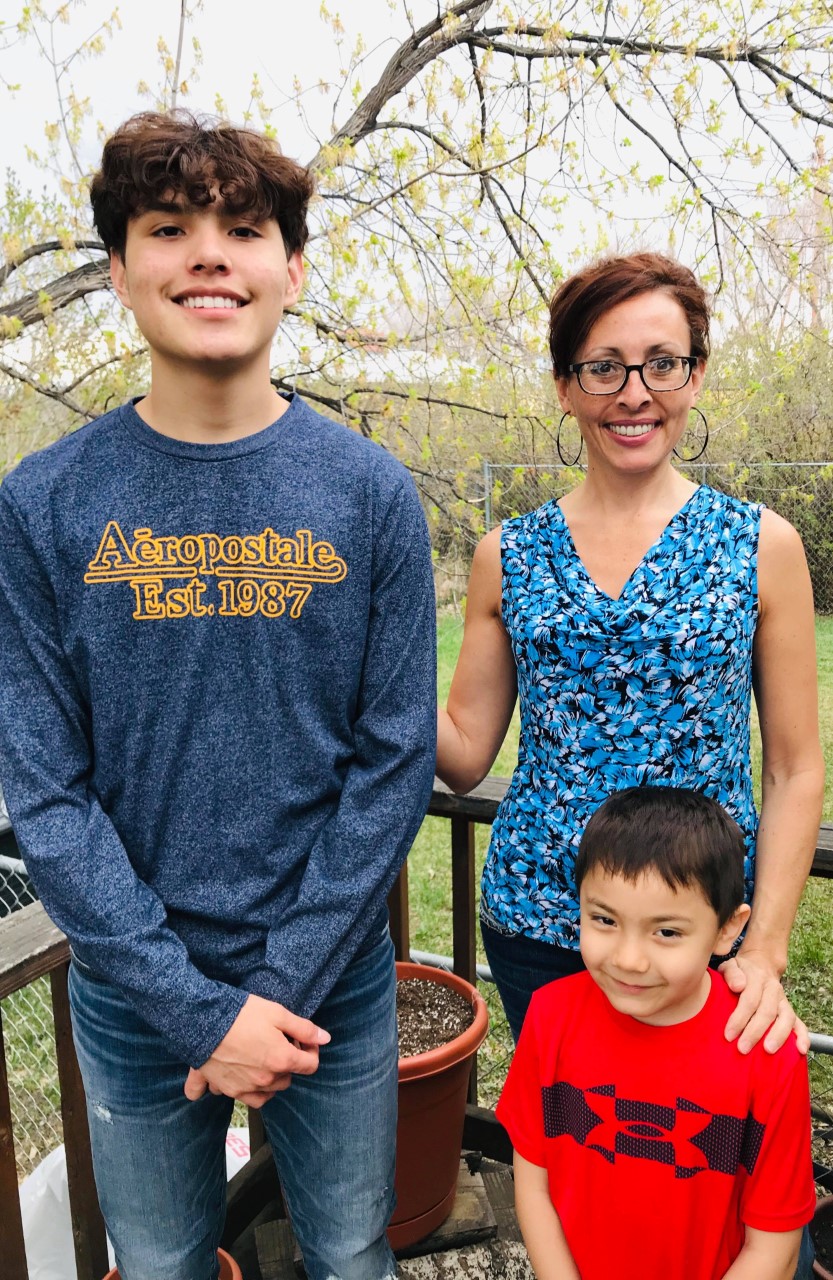

Campbell is one of 31,000 Montanans living on rural, tribal lands without access to Wi-Fi. She lives in the state ranked 50th for broadband access, is a single mother with two school-aged sons, works a now-remote job and has a global pandemic to contend with.

“Here we are, three weeks into this pandemic,” she said in early April. “And we are still struggling with getting internet.”

Campbell said for many in her community, herself included, the only internet they have at home is cell phone data.

As the COVID-19 pandemic and its fallout ripped through the world in March and April, the internet became a lacking necessity rather than a helpful luxury. For those on Montana’s reservations and elsewhere, the internet is critical for everything from education to cultural and community preservation, and yet the utility can be hard to find on some reservations.

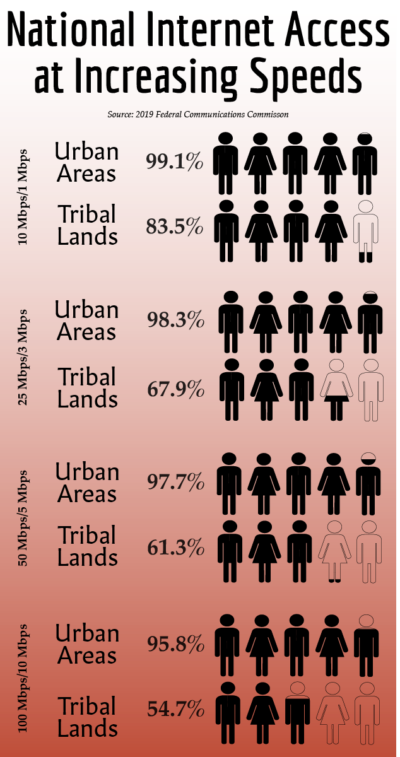

Nationwide, 41% of Americans living on tribal lands in rural areas lack access to fast in-home internet, and when those tribal areas are rural, that jumps to 68%, according to 2016 FCC data on broadband internet deployment.

The digital divide, the uneven distribution of access to the internet, has existed for the past two decades, deepening as technology progresses.

Traci Morris, director of the American Indian Policy Institute at Arizona State University, said the pandemic has brought the digital divide to the forefront as people like Campbell are left with limited ways to stay connected to school, community and family.

“[The divide] hasn’t changed, it just seems more pronounced and highlighted now that we’re dependent on [the internet] in a different way,” Morris said. “It’s getting a light shone on it.”

That light shines brightly on education. Montana Gov. Steve Bullock directed public schools to cancel in-person sessions in March, moving instruction online for most students. This poses a problem for many students in rural districts who only have Wi-Fi access while at school.

On the Fort Belknap reservation where Campbell lives, both students and teachers have had difficulty affording the now-essential internet access at home.

Triangle Communications, the private internet provider that serves a large swath of central Montana, has opened their community Wi-Fi hotspots, making them free to use by any community member. Hotspots are located in most rural communities in their coverage area, but the company said they are not designed for multiple connections at once, and do not replace in-home Wi-Fi.

The company also encourages its customers to work from their home internet, so that people do not violate social distancing rules and congregate at hotspots, but that doesn’t help those who do not have in-home Wi-Fi.

Triangle is negotiating separately with each school district to provide internet packages to students. In the meantime, schools that serve the Fort Belknap reservation have been sending home paper lessons and assignment packets.

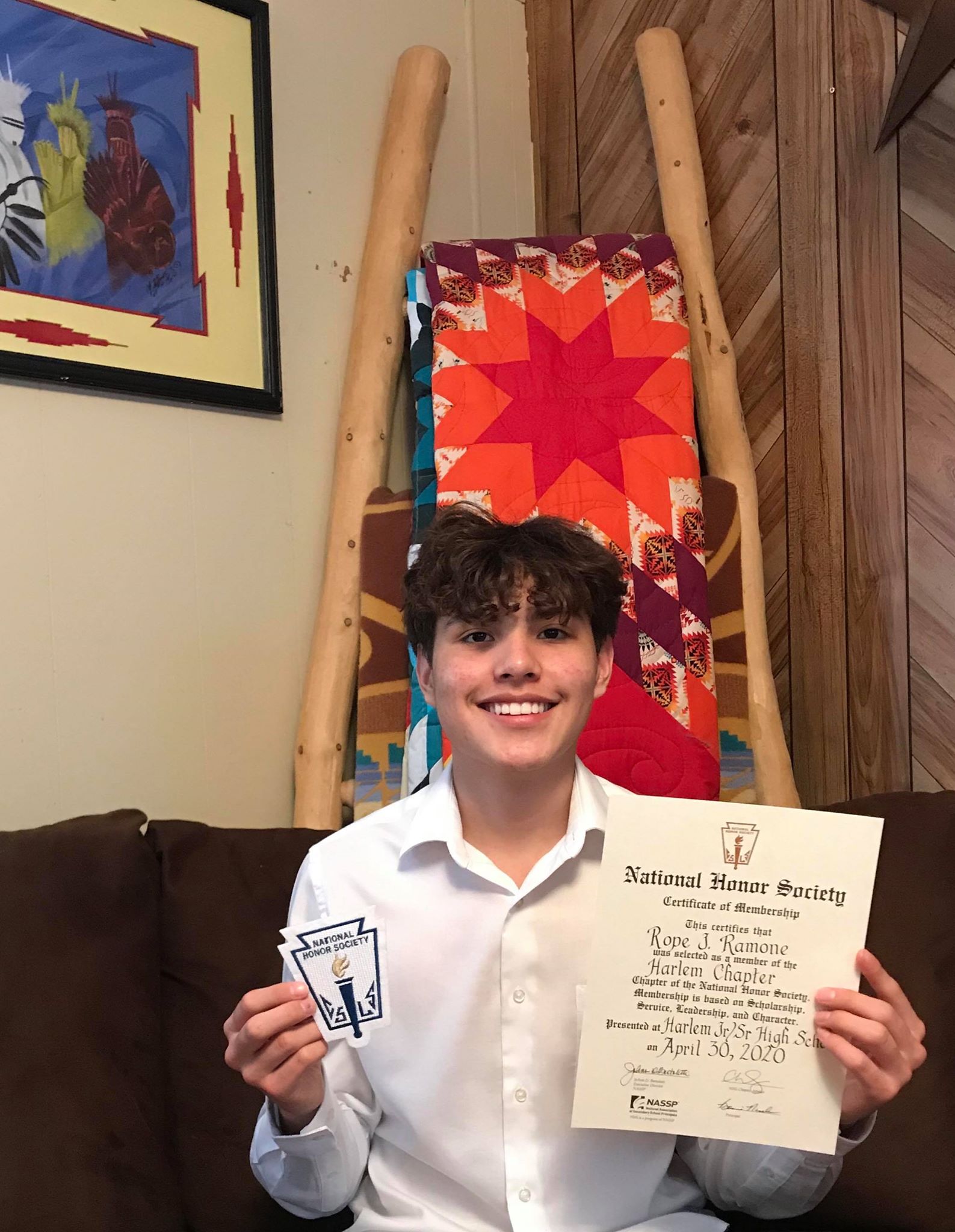

Campbell’s 16-year-old son, R.J., exchanges his homework packets weekly at Harlem High School. Campbell said her son, a 4.0 honors student and athlete, has far more work than before the switch to remote instruction. He communicates with his teachers using his cell phone and handwrites his essays.

Triangle is the only internet company to serve Campbell’s community, putting it in a powerful position.

A 2018 FCC report found that only 21% of tribal households nationwide have more than one internet company to choose from, compared to 56% of non-tribal households. The lack of competition for internet companies serving reservations means an increase of monopolizing and price gouging. Campbell said she cannot justify the expense, especially if the internet is too slow to use.

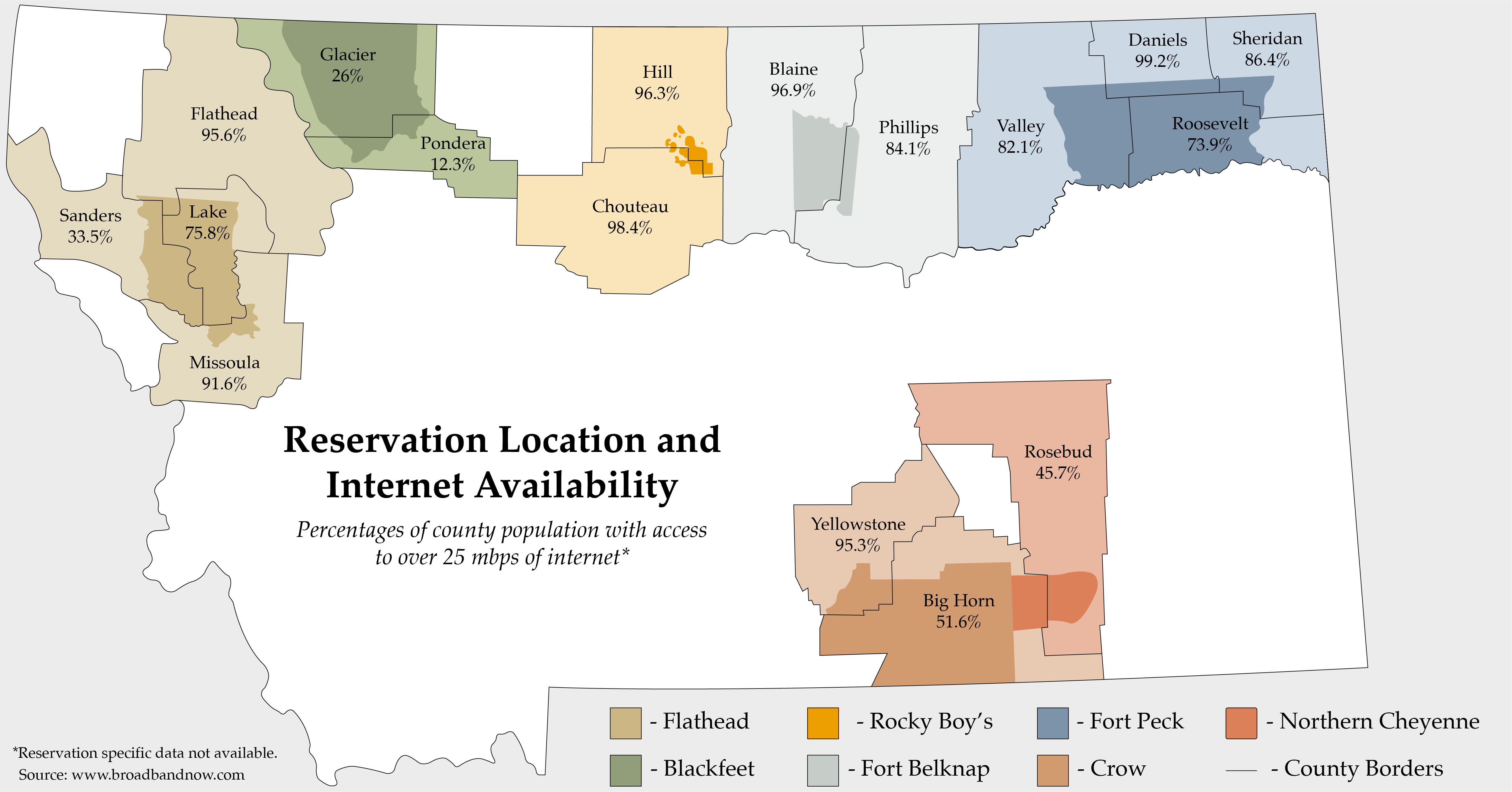

Glacier County, 200 miles west of Fort Belknap and home to the Blackfeet reservation, has the lowest population percentage with fast in-home internet, 25.6%.

Mandy Smoker Broaddus, a practice expert in Indian education for Education Northwest, a Portland-based nonprofit that focuses on advancing education services throughout the Northwest, knew the pandemic would strain rural and reservation schools. An enrolled member of the Assiniboine and Sioux tribes of the Fort Peck reservation, Smoker Broaddus used to be the director of Indian Education in Montana.

“I think a lot of people are very aware of equity gaps really expanding for those that don’t have access or limited access,” she said. “The situations out there are going to vary so widely that it’s really hard for schools especially, rural reservation communities to meet those needs”.

Smoker Broaddus said she has heard stories of school districts parking buses with Wi-Fi around rural towns to provide internet access to students. Most important during this time is communication and transparency with parents, family members and students, she said.

Smoker Broaddus said schools also need to be looking at how and when work is being completed and looking for certain trends including families that might need assistance.

“I think this is an all hands on deck issue,” she said.

Karla Bird, enrolled Blackfeet tribal member and president of Blackfeet Community College (BCC) knew that transitioning to online learning was going to be a challenge for many of her students.

Located in Browning, Montana, students at the community college often live in some of the most remote areas of the country, which creates an inability to access the internet, Bird said.

Blackfeet Community College used an online survey to gather data and found that 46 students, or 15% of the student population, needed immediate help with either borrowing a laptop or getting access to the internet within their home.

“We basically took every computer in our institution, all our laptops and checked them out,” Bird said.

The possibility of a low return rate on the technology equipment or accidental damage was not a drawback as Bird said student success and health is the number one priority.

“Native people are a high-risk population and coronavirus might impact our population more than others due to our health disparities,” Bird said.

In addition to student support, staff members recently participated in a webinar about supporting youth in schools after a community tragedy. Bird, who has a background in counseling, said that everyone needs to be prepared in psychological first aid and rely on fundamentals to get through a crisis.

“We are being forced to do things we didn’t know we were capable of doing,” Bird said.

Multiple community partners have stepped up to offer help including 3 Rivers Communications, a local telecommunications community cooperative.

Don Serido, Market Manager at 3 Rivers, said the company called local schools the Monday the state-wide school closures were announced and offered to provide free internet until May to those who need it.

In order to use their service, homes need to have existing wiring for a land line phone. As of mid-April, the company had serviced over 60 households, 50 of those in Browning and 10 in the Heart Butte area.

“Every couple of days, we get another couple of kids needing internet,” Serido said.

Whispwest, an internet company that services part of the Crow reservation also offered free internet to students.

Kaylee Wesche, a customer care manager, said that students can sign up for 10Mbps unlimited internet that covers streaming for classes.

Graphic by Alyssa Stokovich

In order to install the equipment, a clear line of sight from rooftop to power lines is required. As of April 6th, they have connected 15 households with 10 more signed up for install.

“I foresee people wanting to keep these installs, it’s just easier to manage everything you have to do online with a stable internet connection,” Wesche said.

And there is a lot to do online right now. It’s not just school and work that have made the switch to online. Important social events and community organization have gone online too. There’s even a Facebook page for graduating Indigenous students, the Virtual Indigenous Commencement, to celebrate their now-cancelled graduation ceremonies.

Toma Campbell’s viral cell phone video was posted to one of these social media hubs created to promote and celebrate Native American culture during a time of social distance and anxiety, the Social Distance Powwow.

The group has connected over 145,000 people on Facebook since its inception on March 17. Beside dancing, people have used the page to sell crafts, jewelry, regalia as well as to check on each other and uplift the Indigenous community as a whole. Recently, the group has hosted Facebook Live panels with experts in the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women movement, authors and activists.

Dan Simonds, a Mashantucket Pequot jeweler living in Bozeman, started the group. Simonds was sitting on his couch, contemplating his loss of income due to the cancellation of powwows, conferences and other events where he spends much of his springs and summers.

“A lot of my friends are also artists and vendors and this kind of platform didn’t exist for us, so I figured I needed to create something,” Simonds said. “That’s what I did, and it kind of just went viral.”

Simonds said he wanted to create a positive space for expression and support in the midst of such worldwide fear and anxiety. “You turn on the news and it’s all virus talk,” Simonds said. “I wanted a place to get away from that. We as society should focus more on the good — If you are constantly focused on negative things and negative thoughts, nothing good is going to come from it.”

For Nicole Walksalong and her family, the group has done just that. Two of her daughters, disappointed after the cancellation of their powwow season, posted a front-porch jingle dance in the group. Walksalong said it felt good to see them dancing, and that the platform exemplified the purpose of dance.

“I’ve taught my girls that you’re dancing first and foremost for others who are no longer able to dance, and not to focus on contesting and earning money, and remember that it’s an honor to dance for those who can’t dance anymore,” Walksalong said.

While contesting and earning money is not the focus of dancing for most, there are some who stand to lose a fair amount of their yearly income from event cancellation. Simonds says his business can make up to $40,000 from events each year.

Another Facebook group created a few days later, Quarantine Dance Specials 2020, provides a space for more organized competition, with winners, categories and prize money. Organizer Tiny Rosales said she started the group “to keep the people dancing” and was surprised by how quickly it grew.

“I’m overwhelmed with how everyone is coming together,” she said. “It’s shocking, and it makes me happy when I see these dancers — they put their outfit on, they dance, and they put in effort.”

Rosales started adding prizes for the first, second and third place winners of each competition right from the start, but was soon contacted by the Native American Cultural Center in San Francisco requesting to sponsor the competitions. Since then, she has had private families and organizations reach out to sponsor specials as well. She says her sponsorship calendar through April is looking full.

Participants in the page vote for the winner of each competition and prizes are usually awarded for first-through-third place. “I know a lot of people left home or lost their job, and this just helps out a little more, financially,” Rosales said.

Both Simonds and Rosales said organizing online hasn’t been easy. Challenges like speaking to reporters, enforcing the rules and ensuring information isn’t double-posted can take up a lot of time. Simonds says he sometimes has to turn off his computer and phone to get away from it for a few hours, but that the hard work is worth it to help people connect.

“They’re able to escape all our boxes that we are in, in our houses and kind of be somewhere else with the page,” he said.

Both organizers would like to keep the pages going after life begins to return to normal. Simonds said he may make the move toward a non profit organization or using the page to help create an in-person event.

“It’s crucial to have our voices seen and heard because often we are left out,” he said. “So it’s awesome that we have our own platform. We need our own channels, we need our own media, we need our own voices heard.”

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE:

PREVIOUS: