Sustaining Stewardship

How federal cuts are eroding the foundations of Crow culture

Story by Lucy Decker. Photos by Fox Croasmunchristensen.

The blades of the helicopter pulsed as the United States National Guard flew the archaeology team from the Crow Agency to the Little Big Horn Mountains in northern Wyoming. As the helicopter landed, the drifted December snow dispersed, exposing the landscape below. The sky seemed endless as the views were untouched. The team’s mission was to keep it that way: undisturbed and protected.

The site, which is located south of the Crow Indian Reservation, but would have been a part of the tribe’s traditional homelands, was identified by the National Guard for 50 landing pads for training purposes. The particular location of this build would be inhibiting fasting sites, where the viewshed is just as important as the rock structured fasting beds that lie on the landscape.

In an effort to fight for cultural preservation, half of the proposed territory was denied due to flights impeding the culturally significant viewshed and so the remaining area could be used without specific time restrictions to not disturb fasting quests.

Without the members of the Crow Tribal Historic Preservation Office being present to protect sacred views, stone formations and sites are compromised. Landing sites could be built, plowing over ancient structures and significant pieces of cultural history could be lost.

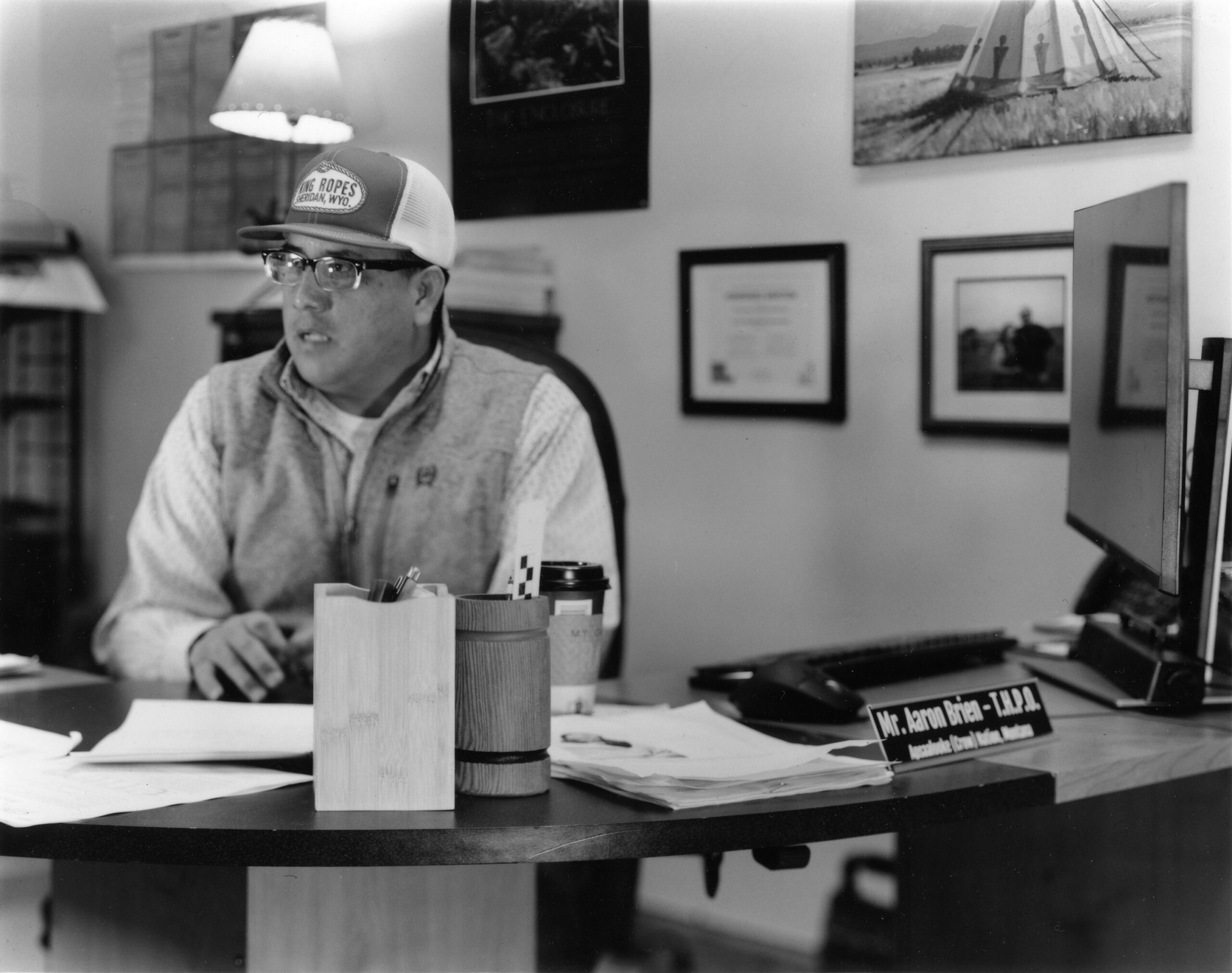

“As a preservation officer, our first love, our first passion, our first relationship is culture,” Aaron Brien, the Crow preservation office director, said. “The job is to protect any aspect of culture, and any time I can do that is a win.”

The Trump administration’s budget cuts to the National Park Service are having a ripple effect that could reach unexpected targets, especially for tribes across the country. These reductions not only hinder efforts to preserve public lands but also exacerbate climate change by limiting conservation initiatives.

Brien is growing increasingly concerned that his efforts to conserve and protect culturally significant sites are at stake for being demolished under various construction projects as funding cuts have taken away resources and staff for preservation offices. The National Parks Service, which once funded preservation efforts, is no longer able to sustain offices across the country. This could lead to Crow culture and history being erased.

When President Donald Trump took office in January, among his first moves was to implement a slew of layoffs throughout the federal government. This included about 1,000 park service employees, mostly probationary workers, which were announced in February. In addition, several federal grants have been canceled or ignored, with $140,000 of frozen funds. Together, these actions have affected the Crow Preservation Office, which falls under the park service.

This is likely not the end of it. Trump’s proposed 2026 budget calls for a cut of more than $1 billion to the National Park Service.

However, Brien said, even in the face of an uncertain future, he will remain focused.

“If I was to lose my job, or if the funding was to go away and I couldn’t do this job anymore, I would be involved in preservation in some fashion,” Brien said. “I could leave this job knowing I had wins. There were moments where I, without a doubt, protected something, or preserved something or reintroduced Crow people to something that had been forgotten.”

Additionally, the Environmental Protection Agency’s clean air and water programs were in the crosshairs and are now being undone. This includes reversing climate change and natural disaster efforts. While worldwide effects are expected to take place, land practitioners of the Crow are hurting to keep their cultural practices alive.

For Indigenous communities like the Crow tribe, the cuts also threaten cultural preservation by restricting access to resources vital for traditional practices. Medicinal healers who rely on the land for gathering essential plants face direct impacts as protected areas shrink and environmental degradation increases. As the National Parks Service funding disappears, both the ecological and cultural heritage of the Crow people are at risk, raising concerns about the long-term consequences of these policies on Indigenous sovereignty, environmental sustainability and the fight against climate change. The landscape is the root of Crow culture.

Brien sits at an L-shaped desk filled with books and papers. Behind him, a map of the Crow reservation fills the wall and his bright red hat contrasts the beige room. The Crow Tribal Preservation Office is located in an old building, a former gas station, next to the tribal museum. The office runs under the authority of the National Historic Preservation Act.

Office staff travel to several surrounding states to preserve the Crow culture. In most cases, the team walks the entire planned construction line of a proposed site, looking for artifacts and signs of culturally significant territory. If there are signs, construction is stopped and reevaluated with the preservation office.

Brien said practitioners of Crow belief and culture are stewards of the landscape. Those who respect the ground they walk on and hold it near and dear to their heart will be given blessings in abundance.

“The root of the whole thing is to protect culture and to preserve as much as we can, because every little piece, it’s all part of this puzzle.” Brien said. “We’re trying to paint a picture of who we are, whatever we can preserve, whatever little part, whatever reconnection we can.”

The office receives thousands of requests per year. The overwhelming volume of requests is then sifted by interest and importance.

“When I say we’re overworked, our capacity for our office does not match the workload,” Brien said. “So what’s coming in and what’s going out, the ratio is bad. So losing any member of that team affects that ratio. So that means it falls on another person.”

Brien regularly deals with complicated interactions between project managers and other archaeologists brought to the site, many are focused more on completing their contracted project than accuracy.

In the Little Bighorn Mountains Project, Brien’s actions put a halt to construction of the landing pads, stalling a project that was slated to start construction this summer. However, under Brien’s determination, the site’s cultural significance deserved more consideration.

“My job isn’t to make friends. And that’s hard because I’m a friendly person by nature,” Brien said. “Our job is to protect cultural resources, and so if that means I have to inconvenience somebody, then I have to. And I take that very seriously.”

Despite the extensive accuracy efforts set in place by Brien, budget cuts and unrealistic expectations are causing stress to the preservation office.

“We receive thousands of requests in a year,” he said. “I mean, I could hire people to help but now we got no money though. We’re not an economic office. We do not want to chase dollars, you know, that threatens the purpose and the job.”

While budget cuts are not final and could change, or be withdrawn entirely, tribal cultural practitioners are concerned with ongoing crises that administrative actions could exacerbate. So far, Trump, who ran his presidential campaign on a promise to “drill, baby, drill,” promoted oil and gas projects and fired scientists and experts responsible for the National Climate Assessment, which tracked the effects of climate change on the nation, according to the New York Times.

“I’ve seen a lot of loss with climate change.” Cedar Rose Bulltail, who owns Cedar Rose Creations, a small business in Crow Agency, said. As part of her business, Bulltail makes medicines and skin care products using plants and herbs considered traditional to the Crow.

However, Bulltail said she noticed that some of the plants she uses are growing in fewer quantities, which she blames on the warming climate.

“Some of our plants require a specific environment to live,” she said.

The Crow Nation is the first tribe to define “Indigenous medicine.” According to the First Nation Medical Board, the Indigenous medical board for traditional medicine, Alvin Not Afraid Jr., the previous Crow tribal chairman, signed a resolution in 2018 that states, “Indigenous medicine is the sum total of the knowledge, skills, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to Native cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness including, but not limited to alternative, complementary, holistic and integrative approaches.”

Bulltail is a well-known medicinal healer on the Crow reservation. Her deep-rooted knowledge of culturally significant plants is the basis for care for many tribal members. Bulltail’s kitchen is lined with every type of glass bottle, tin and dish imaginable. The delicate scent of various heated oils wafts out her door as she infuses her salves and soaps. Her husband stands in the kitchen watching her with a smirk-like smile as he admires her craft.

“I can’t stress it enough. Your medicine is in your backyard,” Bulltail said.

Bulltail’s green thumb is unmatched, but she has noticed a decrease in resources throughout the years.

As budget cuts have stripped away employed stewards of the land, Bulltail is still persistent with her practices.

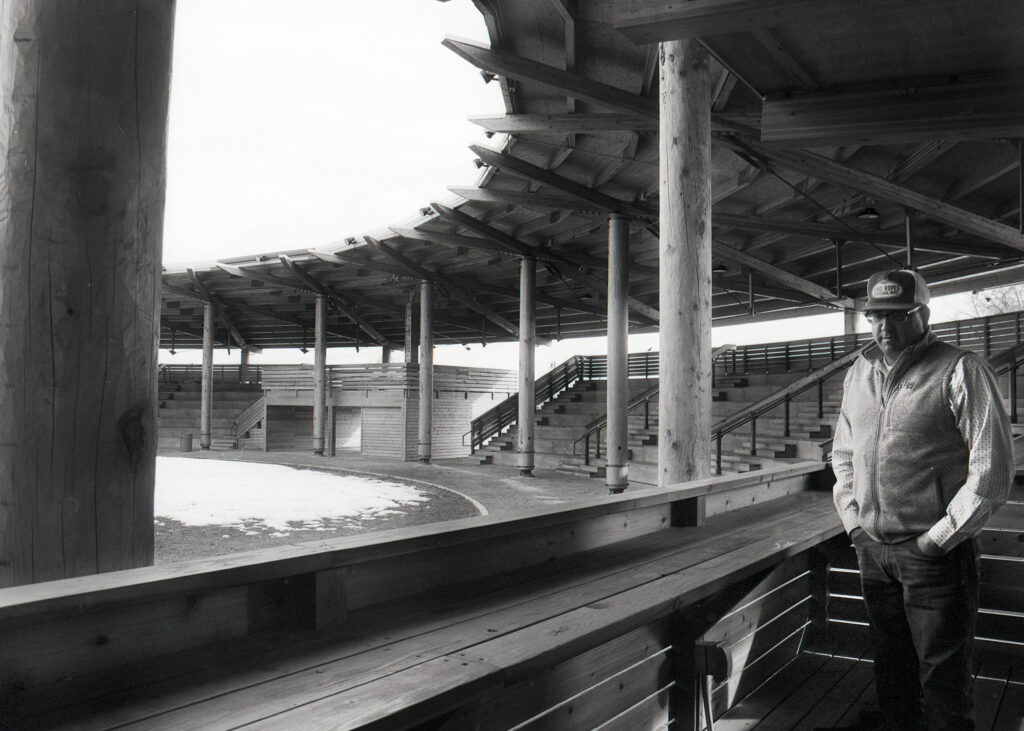

Top: Cedar Rose Bulltail discusses the beginnings of her medicinal practice. Her father died while she was in college, leaving her grieving for years. This grief was connected to her work with mullein after reading that working with mullein is working with grief. Bottom: The setting sun blazes through thin clouds and the low-hanging awning of the east entrance of the Crow Tribal Dance Arbor. The arbor was constructed in 2024 as the culmination of years long efforts to design a new arbor for the Crow Days Powwow.

Mullein, a flowering plant that is used worldwide to fight infections, has been her go to recently because it is readily available and can be easily retrieved without the harm of overharvesting.

“When you are working with mullein you are working with grief,” Bulltail said. She aims to help Crow citizens to heal both physically and mentally from pain and trauma.

Kristen Brengel, Senior Vice President of Government Affairs for the National Parks Conservation Association is actively working on giving a voice to affected offices, regions and groups suffering from the funding cuts.

“When a new administration comes into place…it can really send so many communities into a tailspin.” Brengel said.

The new administration is refusing to host meetings with different sectors being affected by the budget cuts. Brengel notes that this is incredibly worrisome as there are large holes in communication.

When a new administration steps into their roles there is usually a grace period. “But this has been just an attack, a full-frontal assault on so many of us,” Brengel said. “My heart breaks for the tribes.”

Brengel has been focused on ways to increase land stewardship and climate change efforts despite the lack of funding.

“It just sucks because after Biden made all these billions of dollars of investments in clean energy, we are going to stop contributing to it,” Brengel said. “This administration doesn’t think climate change is a problem. There will be a setback for the next four years.”

In 2023, the preservation office commissioned the construction of the Tribal Dance Arbor. The 62,000-square-foot structure is the heart and center of the annual Crow Fair, one of the largest annual gatherings of Indigenous groups in the U.S. It includes traditional powwows, parades, rodeos, horses and dancing. The arbor is packed full with spectators as the surrounding areas are full of food and art vendors.

The arbor was Brien’s idea, and its design was generally drawn up by him as well. Every element used to construct the arbor was made in Montana. He wanted to create a space that held pride for Crow culture. The mouth of the arbor opens up to a circular arena, full of spectacular craftsmanship and design.

During certain hours of the day, the sun peers through the top illuminating the entirety of the inside of the arbor. Although there is no security for the arbor, it is left unharmed. Not a single sign of graffiti or vandalism is present. Brien believes it is because Crow people wanted and needed a prideful cultural space.

“It’s become a safe haven,” Brien said.

***

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE:

Previous

Protecting Education

Next

Standing Alone