Standing Alone

The Little Shell tribe seeks self-sufficiency through economic development

Story by Rose Shimberg. Photos by Owen Preece.

The view from her dining room, which looks out toward a golden-brown hill against a clear blue sky at the western edge of Great Falls, holds a deeper meaning for Julie Mitchell.

“I can see our history from our window,” she said.

The site, known as Hill 57, is where citizens of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians, including Mitchell’s mother, lived in poverty for generations. Segregated from the wider Great Falls community, they were subjected to vicious racism and denied basic necessities, including medical treatment.

“My mom used to say that they settled there because of the sunset,” she said. “It was so beautiful there.”

Beyond Hill 57, there is something bigger on the horizon. It’s a large, flat-topped mountain: Mount Royal. It is the site of a planned multi-million-dollar resort and event center; a project citizens hope will strengthen the tribe’s presence in Great Falls.

Mitchell’s dining room now has a clear view of her tribe’s future.

Since winning its century-long battle for federal recognition in 2019, the Little Shell tribe has leaned heavily into economic development in an effort to reduce its reliance on federal funding. It’s a goal that tribal administrators consider increasingly urgent since the re-election of President Donald Trump. While some are wary about the rapid pace of expansion, hopes are high that economic projects can catapult the tribe to its ultimate goal— complete self-sufficiency.

In his office in Great Falls, Little Shell Chairman Gerald Gray picked up a small, framed photo of himself and other tribal leaders standing behind former President Joe Biden. It was 2023, and Biden had just signed an executive order strengthening tribal sovereignty, giving tribes more freedom in allocating federal funds and redesigning programs to reflect trust in tribal decision-making.

“Trump just rescinded it,” Gray said.

Gifts from other tribes hung on the walls, bestowed to the Little Shell after its recognition. The official document recognizing the tribe, signed by Donald Trump in 2019, hung on an inner wall. The irony of the situation was not lost on Chairman Gray— the man who had granted their long-awaited sovereignty now threatens to strip it away.

Having held his office since 2012, Chairman Gray is often seen as the face of the tribe. He’s a businessman, having worked in research and development at media agency G&G Advertising for more than 20 years. Leveraging this experience, he aims to lead the tribe to economic success.

“When our economic stuff takes off, [we’ll] just tell the government we don’t need [funding],” he said. “Thank you, but give it to a tribe that really needs it.”

Trump’s early-term rhetoric, Gray said, put tribal citizens on edge. The first few weeks of the new administration saw a frenzy of executive orders that sowed chaos throughout Indian Country. This included potential layoffs at the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service, as well as cuts, or pauses, to funding for tribal programs. Although many of the actions have been pulled back, blocked or halted temporarily, the chaos continues, and tribal citizens remain uneasy.

For instance, if a proposed federal funding freeze had remained in effect, work on the Little Shell’s first housing development would have ceased. Its health clinic would have shut down. More abstractly, the freeze represented a disregard for tribal sovereignty, setting a dangerous precedent.

“We want to be self-sufficient. But it’s going to take a little bit of time,” Gray said. “We need to still rely a bit on the federal government [and] hold them to the [treaty] obligations they agreed to. And when they don’t do that, it tramples all over [our] sovereignty.”

The Little Shell announced its resort plans in December 2024. Though permitting will take several years, it’s projected to bring in more than $65 million in annual sales and $9 million in annual tax revenue. It will include a casino, bowling alley, indoor waterpark and a 9,700-person capacity arena. The completed project is expected to provide more than 430 permanent jobs.

Gray is confident that the resort will attract tourism to Great Falls and benefit all residents, further legitimizing the tribe in a community he says is still laced with discrimination.

Rebecca Ingham, the executive director of Great Falls, Montana Tourism, said she first heard about the resort through the December press release. She said the project seems to align with the community’s strategic initiatives to grow its travel industry, presenting an opportunity to host entertainment, trade shows and larger conventions in Great Falls.

“There’s a great need in Great Falls for available convention space,” she said. “The resort does open up the opportunity to bring additional people into our community.”

Open for business

While the resort is the tribe’s biggest project yet, it’s not its first business endeavor. Since 2020, the tribe has steadily expanded and diversified its portfolio under Little Shell Tribal Enterprises, LLC, which manages smaller businesses including a lakeside recreation area, a federal contracting business and travertine quarries.

“We have four or five different opportunities in the mix,” said Brian Adkins, the Economic Development Director for Little Shell Tribal Enterprises. “Probably two or three of them will happen this year.”

The funding, he said, comes from the Pembina Settlement, a class action lawsuit stemming from the U.S. Department of the Interior’s mismanagement of trust funds. While the money was granted in 1985 to descendants of the Pembina Band of Chippewa Indians, the Little Shell tribe couldn’t access its share, $500,000, because it wasn’t federally recognized.

“Here’s the good news,” Adkins said. “It sat in a trust account where the United States government invested it. And [by] the year 2000 it had grown to several million.”

According to Chairman Gray, all of the tribe’s current holdings are turning a small profit, but it’s still feeding back into operating costs. He hopes revenue can soon support a non-discretionary fund for tribal citizens with fewer restrictions than federal dollars.

Like most tribes, the Little Shell still relies heavily on the federal government. The BIA currently funds their government and enrollment, and the Housing and Urban Development supports its housing program, including a major development in the works at the base of Hill 57. The USDA powers its popular food sovereignty program, which is attracting a line of cars around the building less than a year after its formation. Adkins believes returning these services to the tribe is a wise decision in uncertain times.

“Anything that was funded federally is something that should be used with caution, because it may not be there,” he said. “The majority of tribes rely on a lot of federal government money. We want to be in a position where our economic development does that for us.”

Top: Jerrid Gray, project manager for Little Shell Tribal Enterprises, who benefits from employee housing in Paradise Valley, walks above a cut of travertine at the Yellowstone Rock quarry in Gardiner. Bottom: The Little Shell Tribe was federally recognized in 2019 during Donald Trump’s first administration. Little Shell Chairman Gerald Gray keeps a framed copy of this document in his office in Great Falls.

A feeling of home

Not every business venture has worked out. Little Shell Pet Products, a water supplier for home aquariums that the tribe acquired in 2023, quickly shut its doors due to unreliable retail partnerships. The tribe also acquired a gym in Great Falls but eventually sold it when its free tribal membership model didn’t turn a profit.

Cheyenne LaFountain is the former manager of Little Shell Pet Products. Promised a leadership position at one of the tribe’s future acquisitions, she was given a receptionist job to support herself in the meantime. Despite the change in position, LaFountain said she enjoys working for the tribe and supporting its mission of self-sufficiency.

“All it takes is the [federal] government to say, ‘Well, we’re not gonna give you that grant,’ and it can shut the whole system down,” she said. “What Gerald’s trying to build is important.”

The Little Shell tribe was officially landless for much of its history after refusing to sign a 19th century reservation treaty. While offices are located in Great Falls, the tribe now has citizens in all 50 states.

Without a reservation, LaFountain said, locally concentrated citizens have become a huge part of the Great Falls community. But when her father grew up in the area, she said, the intense racism he experienced led him to suppress his Little Shell identity.

“[He was] ashamed to be Native American for a long time,” she said. “He wasn’t immersed in that part of our culture.”

Noel Yelvington is another tribal employee with a long family history in Great Falls. Her mother grew up in a small house on Hill 57 with 13 siblings. Beyond racism from non-Natives, she said, Little Shell citizens faced discrimination from other tribes before they were recognized.

Yelvington has worked as the tribe’s public health nurse for six months, organizing cooking and exercise classes, prevention programs, and naloxone (Narcan) trainings. She said the tribal programs that have sprung up are building a stronger sense of community and identity, which is difficult considering the Little Shell are scattered with no reservation to serve as a tribal home.

“Now that we’re federally recognized and able to do these programs, people are coming together,” she said.

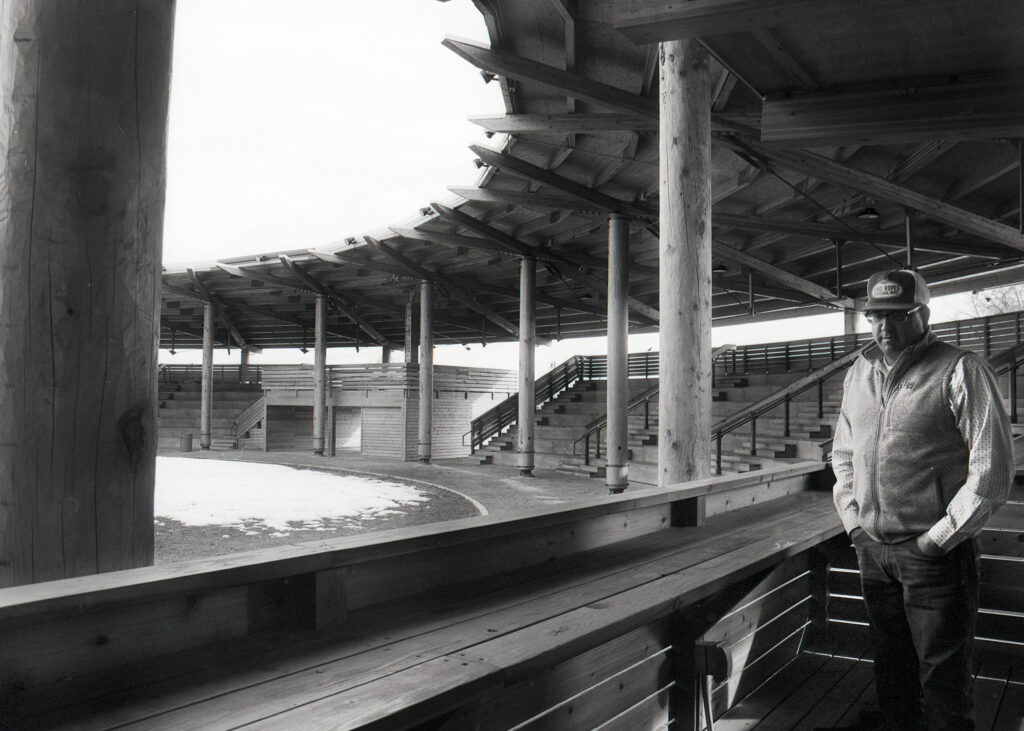

Colton Gray grew up outside of Great Falls, and struggled to connect to his Little Shell identity when he was younger. To him, the resort center and other projects in Great Falls, which include an arbor built over the summer and a patchwork land base surrounding Hill 57, are important steps in connecting the dispersed tribe.

“It’ll give us a bit more of a feeling of home,” he said.

Colton is Chairman Gray’s nephew and one of two employees at the tribe’s travertine quarry in Gardiner. Travertine, formed in Yellowstone’s geothermal landscape, is a soft architectural stone in pure white and rose-colored varieties. In 2020, the tribe bought the company Yellowstone Rock and has been the only domestic travertine supplier ever since.

While Colton prefers to stay out of politics, he’s concerned about the direction the new federal administration is heading and what it could mean for tribes. Economic development is necessary, he said, to ensure a sustainable future.

“If this money starts going back to the members, you’re not relying on the government or anything like that,” he said. “There’s no thumb pressing down.”

His cousin, Jerrid Gray, is the chairman’s son and project manager for multiple businesses owned by the tribe. On a snowy Monday morning, he arrived at a workshop outside of Bozeman and helped craftsman Mark Klette shovel the driveway at Blue Ribbon Nets, the two men joking around as they worked.

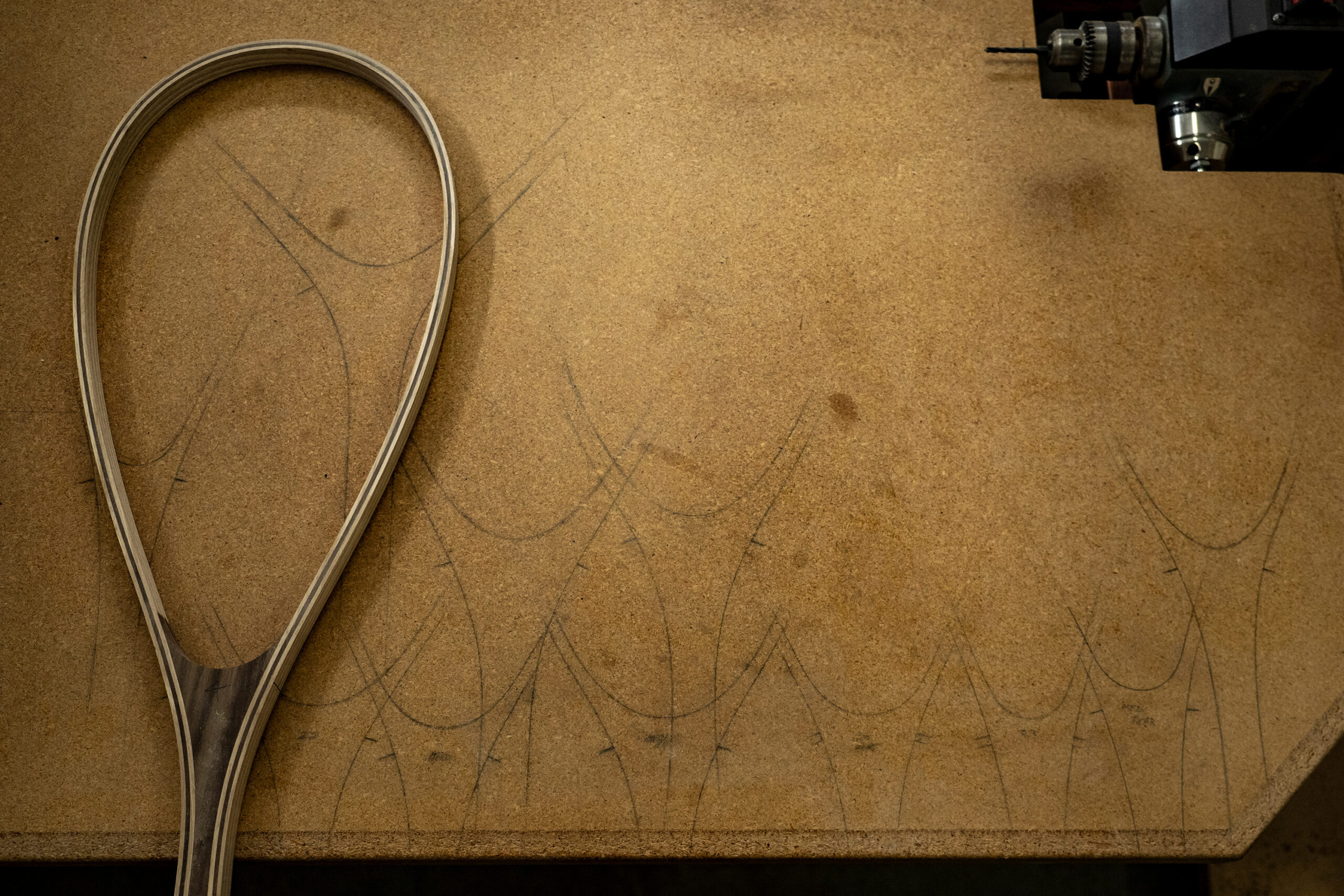

The Little Shell tribe bought the American-made fly-fishing net business in 2021. While Klette stayed on from previous ownership, Jerrid oversees creative direction, putting a Little Shell touch on the products.

“I wanted to design the bottom to resemble a dreamcatcher,” Jerrid said, holding out one of the creations he updated to include a biodegradable net, reflecting values of sustainability.

Though Jerrid is deeply concerned about the Trump administration’s threats to tribal sovereignty, he’s hopeful about his tribe’s momentum.

“The fight has been for so long to even get recognized,” he said. “I think we’ve been like a roller coaster, slowly puttering up and super close to that pinnacle where everything [will] fall into place. That might just be my optimism, but I really hope that’s what happens.”

‘I don’t want them to fail’

While recognition and resulting development are building a home for the Little Shell, it has brought with it a small but vocal group of dissidents, according to Chairman Gray. Tribal enrollment surged post-2019, and some people were upset when they didn’t meet the criteria. Others want direct payment from the federal funding the tribe now receives each year.

“We can’t give them money because the federal government doesn’t allow that,” Chairman Gray said. He said funding is closely monitored. In the face of claims that the tribe is mismanaging federal money, Gray cites years of clean audits.

The tribe receives $480,000 in federal money annually. Gray said if the tribe were to disburse this money, it would amount to $75 per person. It is best used to support projects from which all citizens can benefit, he said.

Still, posting every business decision the tribe makes gives opponents more ammo to use against the tribe’s leaders, he said.

“Anything we do, they turn into a negative,” Gray said.

Top: Craftsman Mark Klette hammers components into a wooden form at Blue Ribbon Nets in Bozeman. This is one of the first steps in making a fishing net by hand. Bottom: Jerrid Gray, project manager for Little Shell Tribal Enterprises, shows off a net featuring a dreamcatcher pattern that he helped design. After the Little Shell tribe took over the business in 2020, they began incorporating biodegradable materials into their nets and marking them with the dreamcatcher motif.

According to Gray, the council has had to take several measures in response to threats from members and non-members, including locking its offices and muting virtual comments on Zoom at quarterly meetings.

But to Julie Mitchell’s daughter, Rylee, that step has made her feel like she has less of a voice from afar. While attending tribal council meetings remotely from Butte, Rylee Mitchell said that while her comments weren’t muted, they were sent through a moderator who could choose whether or not to share them.

Mitchell is aware of tribal business ventures because she stays involved in the meetings and addresses confusion with the chairman directly. But many citizens don’t take that initiative. She believes efforts like including tribal businesses on an easy-to-find website could help build trust.

“It’s just as important for us to be self-reliant,” she said, adding that it’s also important to be transparent.

While Mitchell supports the council’s goal of self-sufficiency, she’s concerned about the pace of the tribe’s expansion.

“My biggest fear is they’re pushing too hard, too fast,” she said.

On top of their economic efforts, the tribe recently announced its intention to take over control of its health clinic from Indian Health Services this summer. Having seen other tribes try to do the same and fail, eventually asking IHS to take them back, Mitchell doesn’t want this to happen to the Little Shell.

“I just don’t want them to fail,” she said.

It’s better to be deliberate than hasty when pursuing economic development, said Ian Record, a Washington D.C.-based consultant who has worked with more than 100 tribal nations. If a tribe’s initial economic development initiatives and specific businesses fail, the community can then be overly risk-averse moving forward.

While Record hasn’t worked with the Little Shell directly, he said that as a newly recognized tribe, it has a clean slate to work from, rather than having to clean up from prior, failed approaches. This opens up all kinds of possibilities for self-determined economic development. The foundational work they do now is critically important to their long-term success.

“You want to make sure that whatever direction you take [is] informed by the tribal citizens, it’s supported by them,” he said. “If an economic development initiative doesn’t have all its ducks in a row, both in terms of having the community on board and having the right people in the room driving it, it tends to fall apart at some point.”

Not fast enough

Back in Great Falls, Julie Mitchell has a similar mindset: she believes her tribe can become self-sufficient if everyone has a voice in the decision-making process.

“We can become self-sufficient if we go the right way,” she said. “If we can work together, and everyone can agree.”

While citizens can express their opinions at quarterly meetings, she believes going a step further and putting out notices directly seeking community input could make people feel like their concerns are heard. Doing so may also address the anger that appears online.

Mitchell is enthusiastic about the planned resort and the job opportunities expected to follow as long as the tribe holds true to its promise to hire qualified tribal employees. In her opinion, a Tribal Employment Rights Office would ensure equal access to opportunities.

Record also emphasized that while it can be hard to find qualified tribal citizens for jobs, it’s important to invest in promising individuals and support the education and training they need to give back to their community— and then hire them for critical roles so they can do just that.

He said the tribe should look to hire the best people in the initial phase. “Some of which may be non-Native,” he said. “But that’s not where you want to stay. You want to ultimately be growing your tribal citizens’ capacity to lead in all of those key economy-building roles.”

Julie Mitchell believes the council is doing the best it can in navigating a tough transition.

“When you’re on council, you have to be the type of leader that helps everybody,” she said. “It doesn’t matter what they do or what they say to you, just swallow your pride, bite your tongue, help them tomorrow.”

Rolling through the golden farmlands outside of Great Falls, Chairman Gray pulled up at an unassuming gate alongside Stuckey Road.

Stepping out of his idling Corolla in a black jacket, jeans and a belt buckle bearing the letter “G,” he went to work on the lock, wind ruffling his hair.

To him, the vast expanse on the other side was a triumph— the tribe, landless for centuries, now manages more than 800 acres, a testament to its growth.

Driving into the expanse, the arbor stood on a windy hilltop with a clear view of Mount Royal, a specter of the event center already on the horizon. A trio of horses trotted and grazed in the distance.

Here, the chairman exuded confidence in his plan to lead the tribe to self-sufficiency, chuckling at the thought of the tribe moving too fast on economic development.

“We’re not moving fast enough,” he said.

The powwow planned for this summer will be the biggest yet, he said, looking out at the brand-new pillars. Citizens from near and far will camp in the sprawling fields, on land that’s finally their own.

Laughing good-naturedly, he got back in his car.

“We’ve got to catch up to everyone else,” he said.

***

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE:

Previous

Sustaining stewardship