A Mathematical Genocide

Tribal enrollment challenges identity on the Blackfeet reservation

Story by Brandon Clark. Photos by Jaydon Green.

It was a windy morning in mid-November, in the parking lot of a Walmart in Great Falls, Montana, the first time Robert Hall got the news that he had become an enrolled citizen of the Blackfeet tribe. The news came after years of fighting, arguing and family research. It was an understated moment that he punctuated by taking his toddler inside and buying her a plush toy of a character from the movie “Lilo and Stitch.”

It felt appropriate, he said.

“Stitch is about Ohana, that means ‘family,’ and family means no one gets left behind,” Hall said. “It was in that moment that I finally felt as if my whole life of being left behind from my tribe, that injustice, was finally cured.”

So, two months later, when the tribal council reversed the decision that granted the 37-year-old his enrollment in the Blackfeet Nation, Hall said he felt a physical reaction.

Enlarge

“When they disenrolled me, they handicapped me,” Hall said.

Hall grew up in Browning, the headquarters of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. He said his experience only showed how both tribal politics and federal policy has so deeply impacted Blackfeet identity with the blood quantum system.

While, like many tribes, the Blackfeet population is decreasing as more enrolled citizens bear descendant children, tribal leaders seem to cling tighter than ever to the system implemented by the U.S. government – a policy that some experts say could eventually dwindle enrolled population numbers into extinction.

Enlarge

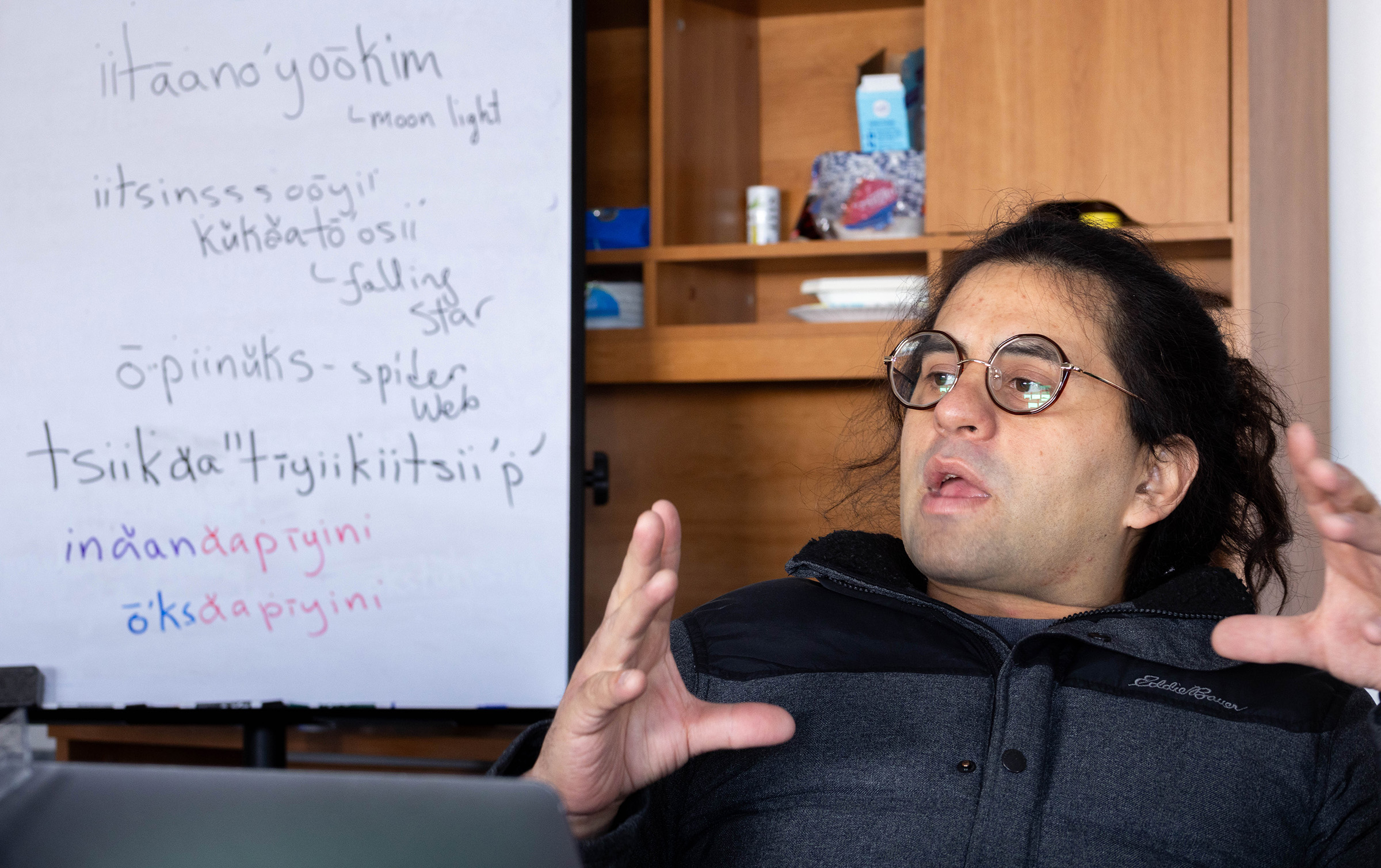

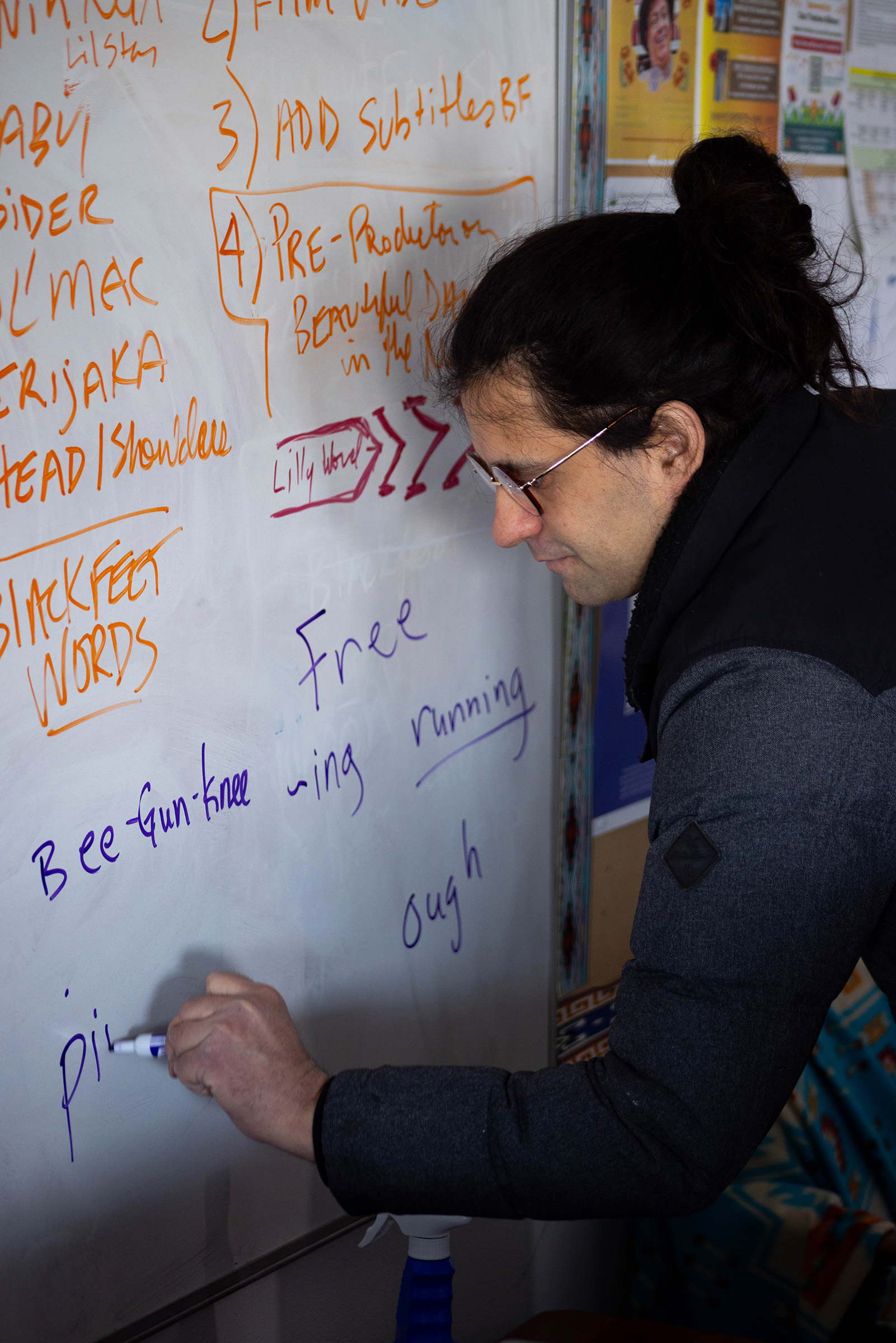

Hall, who has taught the Blackfoot language for years and now serves as the Native American Studies director for Browning Public Schools, had a recorded blood quantum of 15/64, which would put him about 1/64 below the enrollment requirement of one-fourth.

The math is cold and technical.

Instead, Hall was a Blackfeet descendant, a designation that acknowledges he has ancestors who were tribal citizens. While still considered a part of the community, descendants lack certain rights on the reservation, including the ability to own land, vote in tribal elections and to hunt.

Hall said last year, he found documentation showing that his great-great-grandmother had a higher blood quantum than was reflected in the tribal records. While Hall said his family had always been aware of this discrepancy and it was supported by oral history, they didn’t have proof until they found documentation. When they presented their evidence to the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council, the governing body of the Blackfeet Nation, it accepted the documentation as fact.

This decision increased the blood quantum of Grounds’ family after her, including her children and grandchildren. While he was unsure of the exact numbers, Hall said this might have resulted in dozens of additional Blackfeet descendants being enrolled into the tribe, including Hall and his brother.

The next two months were a whirlwind of activity as Hall celebrated his enrollment while continuing his efforts to preserve the Blackfoot language through his work in Browning’s schools. When Browning’s own Lily Gladstone made history at the Golden Globes as the first Indigenous Person to win for Best Actress and delivered her acceptance speech partially in the Blackfoot language, Hall, who taught Gladstone, felt like his work was paying off.

On Jan. 8, Hall received news that at a meeting of the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council the governing body announced a reversal of its previous decision. Mary Grounds’ three-fourths blood quantum would not be accepted.

Enlarge

Hall was no longer enrolled. He called it a sloppy move and said the council members could have taken different actions. The Council has not released a statement explaining why it reversed its decision, but Hall pointed to threats from members of the community and political pressure targeting specific council members as the cause.

Social media posts from that period show how members of the community were worried that Hall’s enrollment could have been done as a “backroom deal,” and raised concerns about transparency. They also accused the Council of playing favorites, given Hall’s role within the community.

Enlarge

Hall said while he disagreed with that representation and believed he had followed the necessary steps as written in the Blackfeet constitution, he understood where they were coming from.

“I do have empathy for [the community members], because they’ve invested a lot of their identity into this idea of blood quantum,” Hall said.

“It pisses me off because people are playing with my family as political pawns,” Hall said. He noted that, if the tribe’s leaders bent to threats of violence, then members of the community unwilling to make those threats would always lose.

“Certain council members need to put their politics aside and honor their constitutional oath, and if they’re going to put their faith in the blood quantum, they should stop attacking families and actually honor documentation,” Hall said.

He has become more vocal in spreading the word that “parts of our citizenship are under attack,” noting if tribal citizens can be disenrolled because of community complaint or threats, no tribal citizen can be secure in their enrollment status.

At a meeting of the Tribal Council on May 2, Hall presented an affidavit showing that his paternal grandfather’s blood quantum had never been adjusted to reflect his great-grandfather’s heritage. Once again, the Council agreed with this documentation and has re-enrolled Hall along with his brother.

“It’s not the Council who made the decision,” Hall said. “It was the Blackfeet constitution. The Council can only honor it.”

The Blackfeet Tribal Business Council did not respond to more than a dozen phone calls over the span of several weeks in March and April.

—

Enlarge

This is not the first controversy involving blood quantum on the Blackfeet reservation. It has been a contentious point over the past few decades and gained momentum in the 2010s through advocacy from Blackfeet Enrollment Amendment Reform (BEAR), a group primarily based on social media, which included Hall as a member.

While BEAR’s attempt to change the Blackfeet constitution failed, in part due to opposition from other groups in the community, the group remains active in its efforts to change the blood quantum system to allow descendants to become enrolled citizens.

Glenda Daisy Gilham-Henderson, an enrolled citizen of the tribe and a lifelong resident of the Blackfeet reservation, said she was initially against enrollment change, often arguing with BEAR members on Facebook.

“You tie your identity, sometimes, into your quantum,” Gilham-Henderson said. “It’s like, ‘We don’t want a bunch of strangers here.’ But when you really put it down, it’s our own people. It’s not strangers at all.”

Gilham-Henderson said she reconsidered and, ultimately, gathered signatures from the community to advocate for enrollment change.

Enlarge

Gilham-Henderson has nine grandchildren, four of whom are over three-fourths blood quantum and can marry anyone they want without endangering their children’s enrollment. Four other grandchildren are between one-fourth and one-half, so they would need to marry another tribal citizen to have enrolled children.

Enlarge

Gilham-Henderson said she changed her mind after she realized that her ninth grandchild’s insufficient blood quantum meant he was not enrolled.

“I wouldn’t want to exclude my own grandson,” she said.

She said that, while she had changed her stance, others in the community had refused to yield, and many elders defended blood quantum despite what she saw as a responsibility to set an example of inclusion for the rest of the community.

She described being shouted at from cars, slapped, shoved and forced to defend herself in fistfights while she gathered signatures for BEAR.

“I’m not proud of that at all, but I was defending myself, because that’s how bad it got,” she said.

“I’ve since become more congenial to those folks,” she said. “I grew up with them, I know them, so it’s hard to be in a small community and have problems with people. So we’ve all buried the hatchet, so to speak, but I would bet 10-to-one if I would bring anything forth ever again, it would go right back to the way it was.”

James St. Goddard, who described himself as a spiritual adviser to the Blackfeet tribe, said that he personally helped to stop BEAR’s enrollment reform effort in his capacity as a tribal lawyer.

“You’re talking to the guy that defeated the enrollment constitution,” St. Goddard said. Still, he shied away from assigning blame to BEAR’s members, saying that the blame fell on grandparents or parents who had married non-tribal citizens. He also noted that it was “the government who wrote up the policies and asked the tribes to pass them, so they could get rid of us.”

Despite saying enrollment policies have caused tremendous damage to the Blackfeet and to Indigenous people, St. Goddard still felt protecting the tribe’s enrollment is crucial to preserving his people’s future.

Enlarge

“We cannot water our tribe down,” he said. “People who want to get enrolled, they should try to understand who the Blackfeet truly are.”

He said the Blackfeet were a smart people and that he had confidence the community could work through the issue without compromising their tribe’s demographics.

“We don’t want to turn into a white society, we want to be a Blackfeet society,” he said. His advice for young descendants was to dedicate themselves to preserving the tribe’s culture regardless of their blood quantum status. “Try to totally learn our language and participate in sweats and the ceremonies – they have that right.”

—

Enlarge

Susan Webber, tribal author and state senator, sat in Browning’s Glacier Peaks Casino and waved at everyone who passed her table, greeting most by name. She raised her voice over the distant echo of early-2000s pop music as it intermingled with the ringing of slot machines.

Webber, who described herself as a historian and educator, drew similarities between the blood quantum system and the antiquated “one-drop rule” used to segregate the Black population throughout the early 20th century and into the 1960s.

“Such beliefs of blood-based identity came from the Middle Ages in Europe and the children of nobles,” Webber said.

“If they had one parent who was a commoner, they were half-bloods, and the others were full-bloods,” she said. “The colonies, knowing this ancient law, brought it over, and it wasn’t for Indians, it was for Blacks that came over. Just like today, they were trying to keep people of color from participating in their local government. They were free, but yet, they were a different color so they instituted the blood quantum.”

She described a scenario of mathematical extinction that could be caused by dwindling blood quantum fractions among the Blackfeet. The tribe could run out of new enrollable citizens as early as 2045, Webber said.

“Native Americans never got to vote until 1962,” Webber said. “Prior to that, why we never got to vote is because we were sitting on trust property. Trust property remains land held in trust by the federal government. We are much like the military bases.”

She noted that, if the Blackfeet tribe does reach a point where new citizens cannot enroll and the tribe functionally ceases to exist by the standards of its own constitution, the land held in trust by the federal government may be taxed and sold without tribal permission to outside buyers. This could result in the Blackfeet reservation shrinking or even disappearing entirely.

Webber described a potential initiative where, rather than changing the Blackfeet constitution, the tribe would instead update rolls so all tribal citizens at the time of the 1962 constitutional amendment would now have full-blood status. She acknowledged this would not alter the current blood quantum system. Instead, it would allow numerous descendants to enroll while also staving off an impending demographic point-of-no-return.

“We have to stop the mathematical genocide that we’re experiencing today,” she said. “And everyone who was on that roll would roll over and their children would be enrolled, all our grandchildren and great grandchildren after that. That’ll give us another 100 years or so to come back and revisit the question of mathematical genocide.”

—

Enlarge

March 26 was a day of celebration for the Blackfeet Nation. It was Lily Gladstone Day.

Community members smiled from ear-to-ear, recording videos and lifting their children over the crowd for a better view. Members of the audience joined in songs and dances, laughing as they rubbed shoulders under the four flags of the Blackfoot Confederacy.

Gladstone, who was born near Kalispell but grew up in Browning, made history when she became the first Indigenous person to win the Golden Globe for Best Actress. Her portrayal of Mollie Burkhart in Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon” also won her a Screen Actors Guild Award.

Robert Hall stood in the back of the Browning Multi-Purpose Arbor with his wife and his children, smiling as broadly as everyone else – Hall was widely reported as a close friend of Gladstone’s in the days and weeks after her award ceremonies. He even taught her a word to use in her acceptance speeches.

Enlarge

When she delivered the first part of her Golden Globes acceptance speech in the Blackfoot language, a dialect of Algonquian, many viewers across the country and around the world were hearing it for the first time.

Enlarge

Hall explained that the word he taught Gladstone – tsiikǎa’’tīyiikiitsii’p’ – translated roughly to, “I feel the goodness of what you have done, I’m a part of it, it’s affecting me.”

This was a celebration of identity, not only for Browning’s Blackfeet community, but for the Blood tribe in Canada, for Mollie Burkhart’s Osage and for Indigenous people who made the commute to Browning in the days prior.

Gladstone began her speech to the crowd – in what has become her signature – by introducing herself in Blackfoot.

“It’s true, if you work hard you can do it. I feel so lucky and so blessed that I’m Blackfeet and I get to be here,” she said to a rising wave of shouts and cheers. “I was brought up, and I continue to be brought up, by all of you. I try to do my best to bring everybody up with me, because that’s what we do, that’s what makes us who we are.”

The Blackfeet Nation honored Gladstone by giving her a stand-up headdress, adorned with eagle feathers that stand straight up. The honor is sacred to the tribe, enough so that many people thought there would be protesters standing against providing such an honor to an unenrolled tribal descendant.

However, no protesters showed – or, if they did, they remained silent. On this day, like Gladstone said, Blackfeet identity was about community, family and helping each other succeed. If anyone had a problem with the fact that Lily Gladstone doesn’t meet the tribe’s enrollment requirement, that was a problem for another day.

After all, even Hall, who was forced through an enrollment roller-coaster by the leaders of the tribe he calls family, recognizes that blood quantum and tribal enrollment is trivial in the grander scheme.

“I didn’t get taller. My IQ didn’t go up or anything,” Hall said of his enrollment. “It was basically just something that happened that should always have been.”

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE:

Previous

Before it’s Forgotten

Next

Surrounded by Séliš