THE LONG RETURN

The Assiniboine and Sioux fight to reclaim sacred items and remains

Story by Haley Yarborough. Photos by Chris Lodman.

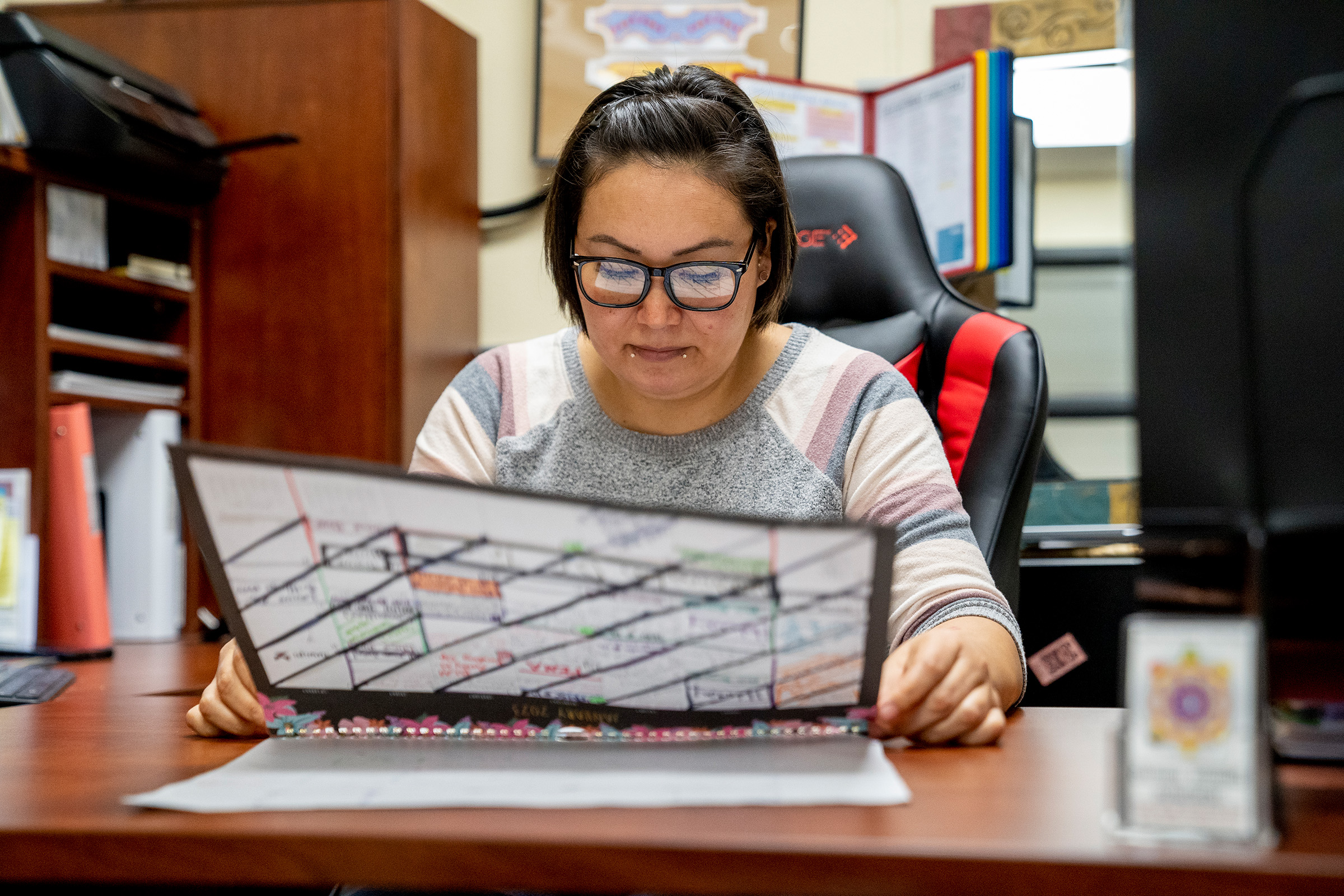

Resting on a cabinet behind Dyan Youpee’s desk is a framed hand drawing of her plans for the future. Six circles surround a sketch of a crescent moon and the sun, each circle dedicated to a different part of her tentative map for a new Cultural Resource Complex for the Assiniboine and Sioux tribes on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation, according to Youpee.

The seven sections etched onto the paper represent the Seven Council Fire or the Oceti Šakowiᶇ Oyate; the confederacy of Native Nations that speak three different dialects of the same language: Nakota, Dakota and Lakota. Youpee is affiliated with all three nations.

The idea for the complex came to Youpee in a dream two years ago. When Youpee told her father about it, he said to draw it out, then jokingly asked how his hair looked in her dream. She said he wasn’t there.

“He told me that’s how you know I’m not going to be there to witness that,” Youpee said. “But man, more than ever I wish I could have worked for my dad.”

For the last five years, Youpee, 36, has worked as the director of the Cultural Resource Department and volunteered as a Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux tribes, working to repatriate items and remains from museums, universities and other institutions.

Currently working on a multitude of repatriation cases, Youpee said the work had been far from easy.

Across the country, museums, universities and other institutions have been slow to repatriate items and human remains to Fort Peck, a challenge similar to many tribes across the United States. The Cultural Resource Department office currently holds cataloged and uncatalogued items from institutions and private collectors across the U.S, according to Youpee. Youpee is also currently working on repatriating remains from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. She said it’s not only vital to have these items and remains returned, but also to have a place to put them. The Fort Peck Tribes have always had space for repatriated remains, and their new cemetery will add to that with a designated space for them.

“Everything has to tie back to the land,” Youpee said. “When it comes to objects, people, even animals, things are created by whatever is buried in the land.”

Enlarge

Despite the challenges Youpee currently faces, she could not imagine doing any other work. Youpee said her work is “generational” in the sense she carries on the legacy of her father, Darrell “Curley” Youpee. Youpee’s father founded the Cultural Resource Dept. in 1995 and worked as director until 2017. He passed away in 2021, but Youpee has carried on his work, shouldering many of the challenges he faced as director.

Amid all her repatriation efforts, Youpee said one of her most daunting tasks has been working to repatriate items and remains from one of the world’s largest museums: the Smithsonian.

This past January, Youpee led a team of more than 10 tribal members and Cultural Resource Department staff to examine items and remains at the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C. She was surprised by the vast number of Lakota, Nakota and Dakota items held there.

“I could have just looked at all these pictures online, but it did mean something to touch them, touch them and tell them I’m going to come back,” Youpee said.

While Youpee plans to get repatriated items returned to Fort Peck on loan from the Museum of the American Indian, she has not yet filed for repatriation from either museum. With a small staff and an office Youpee hopes to expand, she stressed that institutions need to make the process easier for tribes seeking to repatriate.

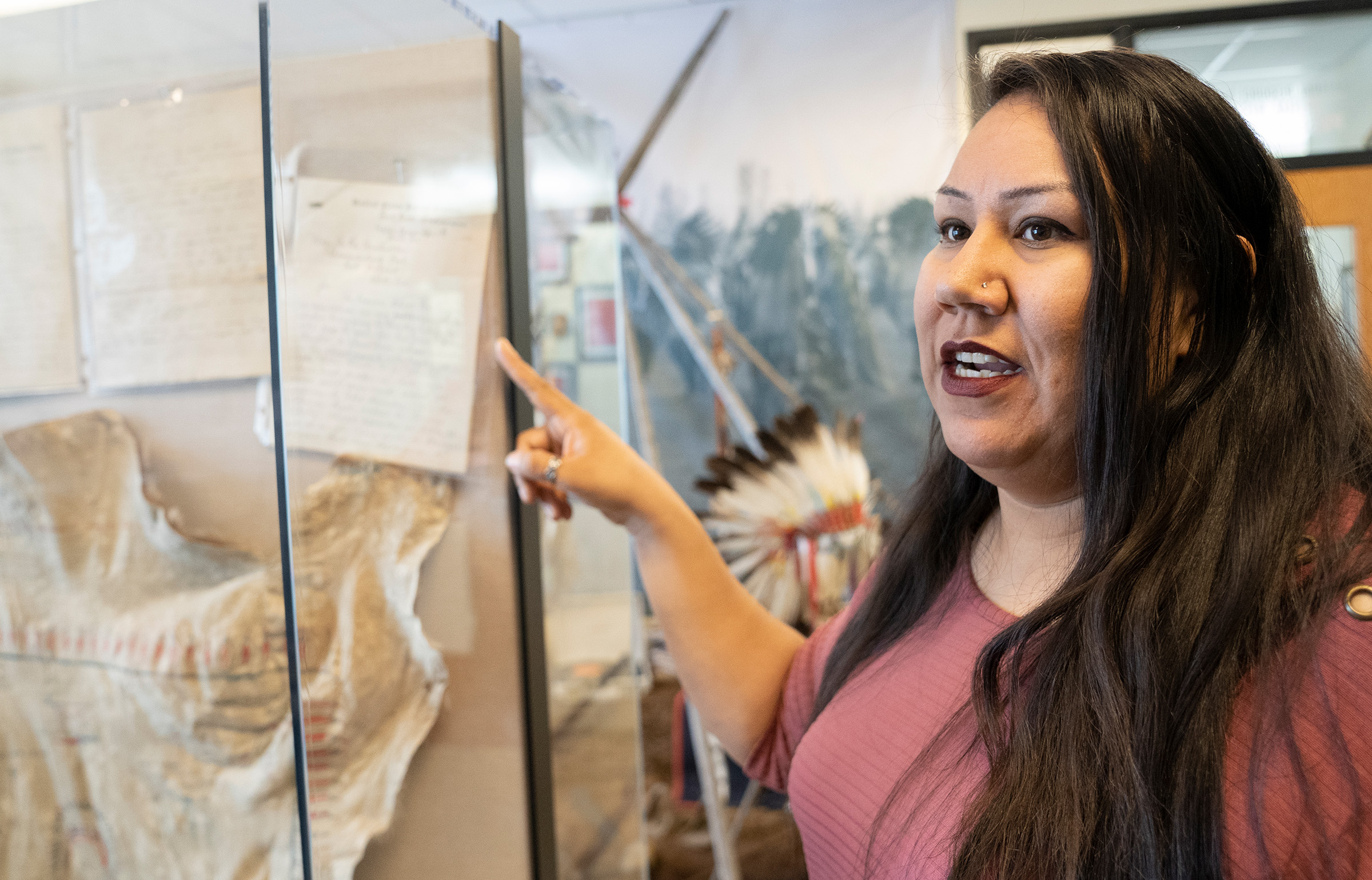

Top image: Chantell Buckles discusses her work as an intern for Fort Peck’s Cultural Resource Department over the summer. As an intern, Buckles handled documents repatriated from institutions and museums across the United States. Bottom image: In the Cultural Resource Center, Chantell Buckles examines an envelope with a magnifying glass as part of her duties as an intern, which include transcribing, cataloging and organizing documents.

Policies and Procedures

Many institutions, including the Smithsonian, hold art, artifacts and remains that can be traced to the 19th century when the United States removed Native Americans from their homelands for westward expansion, often encouraging the looting of Indigenous remains, funerary objects and cultural items.

Shannon O’Loughlin, the Chief Executive for the Association of American Indian Affairs and a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, said in addition to these items and remains being exploited for purposes of “research,” they were also exploited for profit. Many objects obtained by the Smithsonian in the 1800s were dispersed to schools, museums and private collections across North, Central and South America.

“The U.S. was seeking to dismember native homelands and native bodies for scientific purposes, but also for commercial interests,” O’Loughlin said. “So along with the science, there was also a burgeoning market economy, selling tribal antiquities, which were funerary objects, which were human remains and sacred objects. They became trophies of war.”

In the late 1980s, the Smithsonian found its reputation at risk after revealing it held 18,500 Native American human remains. Despite anthropologist’s defenses to keep items and remains in museums’ possession, mounting pressure on the Smithsonian in 1989 prompted the creation of the United States’ first repatriation law, the National Museum of the American Indian Act, which called to repatriate thousands of skeletal remains to their tribes.

In 1990, the U.S. established its second repatriation law, the Native American Graves and Protection Act, or NAGPRA, a kind of mandate for federally-funded agencies and museums to return Native American human remains and certain cultural items to tribes upon assessment, including funerary objects, sacred ceremonial materials and items of tribal patrimony.

Around 62% of the Smithsonian is federally funded as of 2021, but it falls under the former NMAI Act, according to the Smithsonian website.

Of the Smithsonian Institution’s 19 individual museums, only the Smithsonian’s Museum of the American Indian and Museum of Natural History hold collections to which the repatriation legislation applies. The two museums maintain separate repatriation programs with unique policies and procedures.

For Fort Peck’s Cultural Resource Department, this resulted in a vastly different experience with both museums.

Youpee said her experience with the Museum of Natural History was frustrating, while she found her time with the Museum of the American Indian far more pleasant and accommodating. Over four days, the Cultural Resource Dept. visited with human remains taken from Montana and combed through hundreds of objects, according to Youpee.

Youpee said while at the Museum of Natural History, she had to parallel the descriptions of a certain object with those provided by “collectors” and “looters.” She recalled how a drum was confused with a tambourine, but she had to keep the description as “tambourine” to provide a description “in the context it was found.”

“I don’t know how anyone thinks they can tell us what an item is when we’re the ones that have them hanging on our walls, that we utilize on a daily basis,” Youpee said.

Bill Billeck, the Museum of Natural History Repatriation program manager, said errors in the descriptions often occur because of the “inadequate” descriptions provided by the people who sent the item to the Smithsonian.

For remains, the repatriation process is relatively straightforward, unless a remain is “culturally modified” or altered to become part of another object. Because human remains are not defined under the National Museum of the American Indian Act of 1989, Billeck said the line between human remains and cultural objects can be blurred if something is culturally modified.

Objects are a little more complicated. The Smithsonian currently holds nearly 155 million objects, works of art and specimens, and approximately 146 million belong to the Museum of Natural History, according to the Smithsonian Website. Because of the sheer quantity of items it holds, Billeck said that sometimes the objects have no descriptions, the descriptions are wrong or the descriptions are generalized.

“In most cases, the descriptions are very generic so someone can search for the item,” Billeck said. “But they may not be culturally relevant to restitution. It may say something is a bag, but what kind of bag? We may not know what kind of bag.”

For the repatriation program at the Museum of Natural History to become more efficient, Billeck said the Smithsonian will likely have to increase the number of staff in the repatriation office.

The Smithsonian has made available for repatriation the remains of more than 6,000 individuals, 250,000 funerary objects and 1,400 sacred items of cultural patrimony as of 2020, according to the Smithsonian website. With around seven employees, Billeck hopes to add at least two more staff members to the repatriation team. He said managing repatriation is a heavy burden to manage alone.

“We are responsible for repatriating one of the largest collections of human remains in the United States,” Billeck said. “We have a lot of work to do.”

Enlarge

Fighting for change

While in the U.S. capital, Youpee and two other tribal members called Sen. Jon Tester’s office to talk about their experience with the Museum of Natural History’s repatriation process.

Currently, Tester is working to craft a 2024 fiscal appropriation bill that directs the Smithsonian to improve its repatriation policy with the tribes and other ways to improve the repatriation process, according to a written statement from his office.

Fort Peck Tribal Chairman Floyd Azure also plans to visit Washington D.C. to meet with congressional representatives and the Museum of Natural History to discuss their repatriation policies and procedures.

Azure is currently serving his second consecutive term for the Assiniboine and Sioux tribes. He’s known Youpee for around five years and worked with her father before he passed away. In his experience with talking with institutions about repatriation, he said there’s often not much he can do.

Enlarge

“There are certain things that we can ask (the institutions) to do, but a lot of the time they tell me they can’t do anything because of federal regulations,” Azure said.

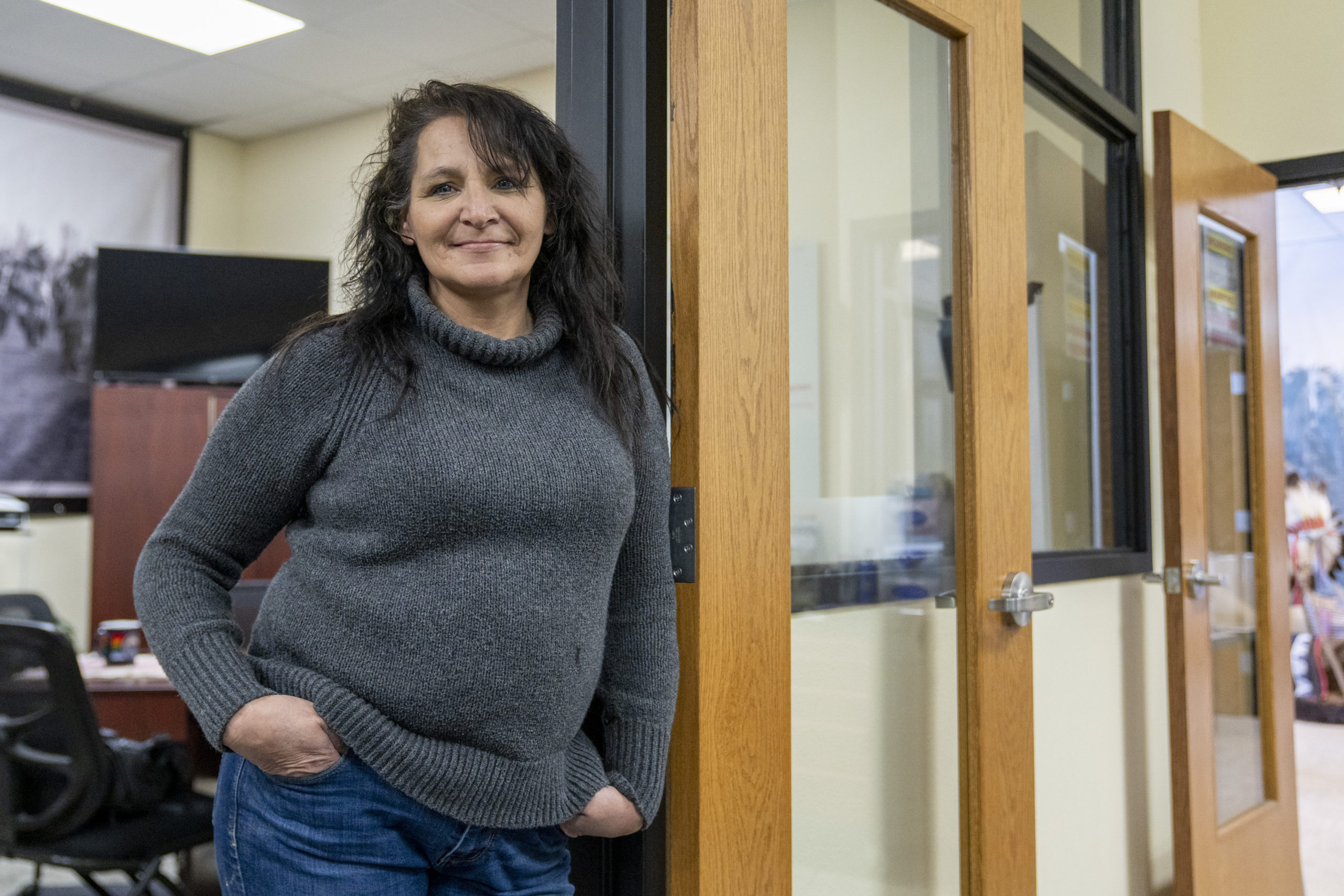

The implications of repatriating with the Smithsonian is a reality Cindy Morales knows well.

Morales is a non-tribal member from Walla Walla, Washington, who served as an intern and did contract work for the Museum of Natural History Repatriation office before she became an intern and the museum coordinator for the Cultural Resource Department. She now works as a career advisor at Poplar High School and accompanied Youpee on her trip to the Smithsonian in January.

During her time with the Smithsonian, Morales researched items and remains for repatriation. She said to compile the back history of an object or a remain alone usually takes a month because the items often are missing key information.

“Often times the (items) have been transferred from museums or other institutions several times,” Morales said. “So they have to dig through all that information and see what’s relevant to that specific item because they were often moved altogether.”

Visiting the Smithsonian, Morales said she can understand why the Fort Peck Tribes were unable to return to the reservation with items and remains. She said in her experience there’s no “easy” way to do repatriation, but that museums and other institutions should do their best to accommodate tribes visiting and seeking to repatriate.

“They’re trying to do it in a way to make the least amount of mistakes possible, which I can understand,” Morales said. “But people have waited long enough for the ancestors. I think they need to understand how much pain it causes for members of the tribe.”

Enlarge

Seeking Connection

In Cheryl Nygaard’s camera roll is a photo of a pair of her grandfather’s buckskin leggings.

Nygaard took the picture while at the Museum of the American Indian as they examined items and remains available for repatriation for the Fort Peck Tribes. Nygaard said it was one of the most memorable trips she can remember while working at the Cultural Resource Department.

“When they brought them out, it just took my breath away,” she said.

Nygaard, both Assiniboine and Sioux and a current student at Fort Peck Community College, has worked for the Cultural Resource Department for about a year as the Section 106 reviewer, overseeing federal projects on tribal land to ensure that historic preservation is considered.

The leggings belonged to Nygaard’s grandfather, Alexander Culbertson, a leader in the fur trade and the founder of Fort Benton, Montana. From Pennsylvania, Culbertson was white but married Natwista Iksina, a Kainah interpreter and diplomat.

Nygaard said she did not even know the leggings belonged to him until she looked them up in the Smithsonian’s archives and discovered their connection to Culbertson.

“I had no clue they belonged to my family, no clue,” Nygaard said. “When they brought them out, I just felt super emotional. I cried.”

Beyond the office, The Cultural Resource Department’s work has been a way for the Assiniboine and Sioux tribes to reconnect with ancestors lost over 100 years ago.

Currently, the Cultural Resource Department is in the process of repatriating two sets of remains from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, a boarding school where hundreds of Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their homeland to assimilate with white Western culture. More than 150 children were buried at Carlisle, according to the Office of Cemeteries website.

Although these children were buried on federal lands, NAGPRA does not apply to Carlisle. Instead, the Army has instituted its own process of repatriation. To recover the remains, there has to be a direct living descendant connected to the children.

Even though Youpee is early in the process of repatriation, she said she connected with one of the living descendants of the remains recovered from Carlisle Boarding School.

When Youpee recovers a set of remains, if the family chooses, the remains may be buried in a designated space at the Fort Peck Tribe’s new cemetery.

Top image: Bob Kelsey, who volunteered at the Poplar City Cemetery for nearly 20 years, sold the tribe the land for the new tribal cemetery. In Kelsey’s time at the cemetery, he has helped many community members find family members’ lost burial sites. Bottom image: The Minisdah Presbyterian Church in Chelsea on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation has a cemetery with grave sites dating back to the early 1900s.

A place to rest

Last June, the Cultural Resource Department buried the remains of two Dakota Sioux women recovered from the State Museum of Pennsylvania in Fort Peck’s new tribal cemetery.

The newly developed cemetery, which spans about 15 acres, contains approximately 4,000 grave sites. One hundred and sixty are dedicated to repatriated remains.

The Sioux women’s remains were removed from box graves on the prairie of the Fort Peck reservation, according to the University of Pennsylvania curator, Robert Stewart Culin. While no known individuals were identified by name for the remains, the Cultural Resource Department held a “Returning to the Earth Reburial Ceremony” — a ceremony where remains are buried directly into the soil, without the use of a coffin or embalming.

Top image: The new tribal cemetery spans 15 acres in East Poplar and holds roughly 4,000 graves, with 160 of the graves dedicated to repatriated remains. Just last June, the Cultural Resource Dept. repatriated two remains from the state museum in Pennsylvania and buried them in this cemetery. Bottom image: The Poplar City Cemetery has roughly 3,970 graves. According to Bob Kelsey, a former volunteer at the cemetery who frequently looked over cemetery records, a few hundred plots are still available. Still, because of the cemetery’s age and prior management, there is little room for equipment or space needed for new burials.

“The ceremony is basically acknowledging a heartbeat in the earth,” Youpee said. “Once we put the remains back in there, it becomes a heartbeat across the Indian reservation in hopes we can bring more relatives home.”

Councilwoman Patt Iron Cloud, 70, said it’s vital to have a place for repatriated remains to rest. Iron Cloud’s great grandmother attended the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in the early 1900s but passed away on Fort Peck Indian Reservation in 1984. Iron Cloud said it’s important not only where remains are buried, but how they’re buried. As a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, she does not believe in cremation and said dirt burials are important in her beliefs.

Top image: Patt Iron Cloud drives through the almost-full Poplar City Cemetery, pointing to her family’s graves. In her lifetime, she has lost 10 of her children. “I’ve realized life is real fragile,” Iron Cloud said. “We never know when we’re going to go, but we have to be ready.” Bottom image: Patt “Grandma Patt” Iron Cloud, 70, has 50 grandkids and serves as a Fort Peck councilperson. Iron Cloud ran for council to better care for the families of the tribe. “Our families were just falling apart here. And a lot of our children were being put in foster homes and breaking up as a family,” she said.

“I need to know where my bones are gonna lay, not my ashes, my bones,” Iron Cloud said.

After COVID-19 increased the demand for grave sites on the reservation in 2020, some members of the tribe did not know where they would be buried, or if they could be buried close to family. The current city cemetery only holds approximately 100 available plots, according to Bob Kelsey, a since-retired businessman who has volunteered to help manage the City of Poplar cemetery for 20 years. A few years ago, Kelsey sold 40 acres of land to the Fort Peck Tribes, the same plot of land being used for the cemetery.

Iron Cloud said she’s glad there’s a place for her, her ancestors and her future grandchildren to be buried.

Enlarge

‘This work is never done’

Sitting at her desk in the cultural resource office, Dyan Youpee flips through a calender with her week-to-week plans. The calendar is filled with conferences, upcoming trips to repatriate and training sessions for new interns. Youpee said she can’t remember the last time she had a vacation.

“Honestly, I kind of gave up my personal life to advance my professional life,” Youpee said. “It’s really just working, go home, eat, play with my nieces and then go back to work again.”

Even with her busy schedule, Youpee said she’s holding onto her plans to build a new Cultural Resource Complex. While she needs to secure funds for the complex, Youpee tentatively hopes to start construction in a few years.

“I feel like I could have given this to my dad and he could have taken it further,” Youpee said. “He was hard on himself. I’m hard on myself.”

Despite her doubts, Youpee said she could not imagine doing any other work. Just as her father taught her about repatriation, Youpee is passing her knowledge on to her niece, Madelynn. She said even with someone to potentially take on her profession, until all the items and remains are returned to Fort Peck, she will always have more work to do.

“This work is never done,” she sighed. “This work is going to follow me into the next life.”

A SPECIAL PROJECT BY THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM

ADDITIONAL FUNDING SUPPORT FROM THE GREATER MONTANA FOUNDATION

READ MORE:

Next

An Empowered Future