Saved by the Bell

The bittersweet return to school

Written by Alex Miller, Photos by Hazel Cramer

School was out. But the shrill, electronic school bell drone blasted throughout Lame Deer High School. It should have been a short burst, but it went on for minutes.

The blast rang from the white, tile-shaped speaker situated in the ceiling of the athletic director’s office. Senior basketball player and student Madison Doney sat among the clutter of the office, filled with freshly sanitized basketballs, golf clubs and shooting machines. She paused and cocked her head toward the ceiling.

“He must still be trying to get it right,” Doney said with a laugh.

This was in March, only the second day of the school’s reopening, and the first day they used the bell all year. Principal Byron Woods had forgotten to set the bell the day before, and was still trying to work out the kinks in a system that had been dormant since the start of the pandemic.

Woods’ office is neat and tidy, with his impressive fat tire bike securely fastened to a towering stand. A Bob Ross Chia Pet smiles over his shoulder, its clay head still bald.

“Two weeks turned into another two weeks, and pretty soon it became apparent that we’re not coming back,” Woods said, recalling the early days of the pandemic.

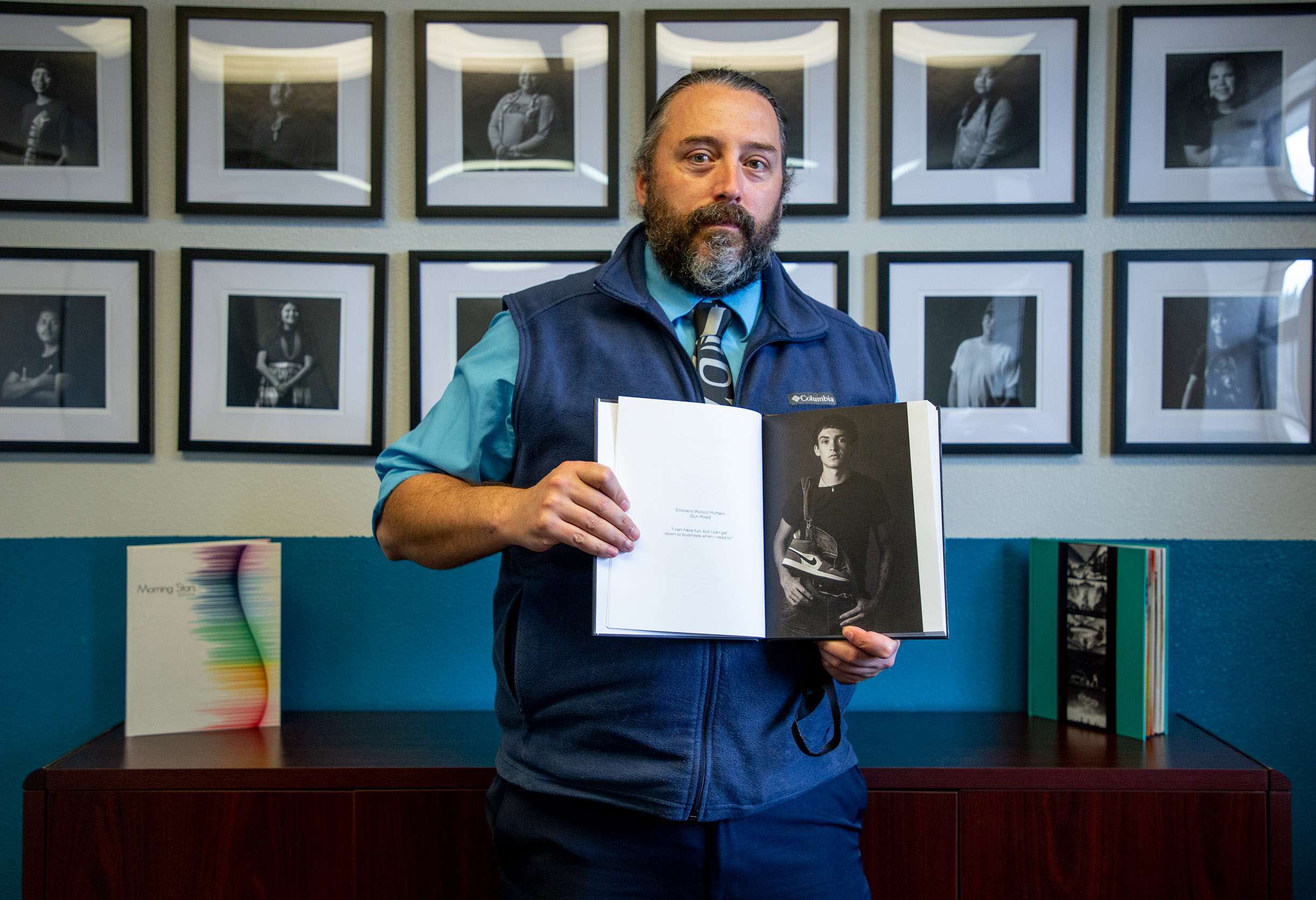

Enlarge

Woods is coming up on the end of his second school year as principal. This is the first time the principal has seen all of the students in one place this school year. This day, in late March, was the culmination of a long, difficult journey taken on by him and his staff.

“I think everybody has been in survival mode,” Woods said.

Lame Deer High School, situated a few miles down the main drag of Lame Deer, Montana, reopened in late March 2021. The first three days of reopening the school were treated like orientation days, with the real first day coming Thursday, March 25. Some remembered the halls from years past, others had never set foot in the building.

Lame Deer High School was one of the last schools to open in eastern Montana, teaching remotely through the pandemic. Without a school, the community found it had little to tie itself together. Gone were the face-to-face interactions of teacher and student.

Gone also were the fundraisers, meetings, a lot of community that happens at schools, though perhaps most detrimental was the absence of sports.

During the continued struggle of the pandemic, schools needed help. Lame Deer High School, along with schools across the country, received CARES Act funding in the form of Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief, or ESSER, funds. The CARES Act allocated $13.5 billion nationwide for struggling schools, with more than $41 million going to schools in Montana.

For students, this meant money to speed up the evolution from the printed paper packets full of busy work sent out in spring 2020 to the glowing screens of Google Chromebooks last fall.

Since the initial wave of funding arrived in March 2020, two additional ESSER pools have been filled. A second national injection came in December 2020 with over $54 billion, and a third arrived in March with the passing of the American Rescue Plan Act. That third round saw over $122 billion allocated to the ESSER fund. Currently, the Montana Legislature is hammering out how to spend the combined $552 million.

Woods said that they had built a plan, mostly from work done by athletic director August Scalpcane, to get the kids back by the fall of 2020. But the ever-increasing spread of COVID-19 within the small town of more than 2,000 kept the doors of Lame Deer High School shut.

As of April 2021, the Northern Cheyenne had accumulated 957 COVID-19 cases, with 46 deaths. Over 19% of the reservation has been affected by the virus.

“The teacher’s union was concerned. We have an older staff, so that was a little scary,” Woods said.

And so the kids were left to continue learning from a distance. Getting students to engage online was tough, teaching through a computer screen meant each student is likely surrounded by countless distractions. The halls, the classrooms where teachers can gauge student interaction, were forced to remain empty.

But Scalpcane had an idea: If they could safely have a basketball season with 40 kids all together, they could bring back the community around school.

Doney, the center on the girls basketball team, would have her final first day of school almost seven months late. Doney had moved from the Fort Belknap reservation when she was in sixth grade and has been in the Lame Deer school system ever since.

Enlarge

She had big plans for her senior year. For the three-sport athlete, her main goal was to make the all-conference first team for basketball. But with the pandemic forcefully closing the door on the waning moments of her junior year and the bulk of her senior year, she, like many others, was left in a state of limbo.

“I don’t feel like a senior,” Doney said.

Doney, along with her classmates, experienced a year filled with isolation, depression, death and uncertainty of the future.

***

The effects of COVID-19 extended beyond its victims’ health. Schools across Montana, and the U.S., faced a similar question in the fall of 2020: What is the risk of reopening? For some schools, like Ashland Public School and St. Labre Indian School, reopening, using a hybrid online and in-person model, came as early as the start of the new school year in the pandemic era.

In the case of Lame Deer, administrators decided to use the $260,000 to purchase Google Chromebooks, charging stations, laptop sanitizers, personal protective equipment and a touchscreen thermometer at the school entrance that greets visitors. Delivering two meals a day to students took a piece of the ESSER pie as well.

Much of the student body at both St. Labre and Ashland Public already had access to Chromebooks. Lame Deer was behind. Its Chromebooks would not come until the start of the new school year. When the pandemic hit, teachers switched from classrooms to paper packets.

Gone were the interactions of teachers and students, replaced instead with a still, forgettable, piece of paper. Many students struggled with the packets. The motivation to actually get the work done was low. The school managed to deliver packets, along with two meals per day, to 98% of its students. Less than a third of the packets were returned.

Doney struggled as well. When school was closed, she and her friends were excited at first to get a break from the grind of the school year. But then she began to worry about her work.

“We still did everything normal, just no school,” Doney said. “Until we finally started getting packets from the school. Everyone was still hyped about it, but me, I didn’t have the motivation to work from home.”

But for senior classmate Davinia Osife, who grew up in Lame Deer, the packets helped. She had struggled with getting to school on time prior to lockdown, but with no classroom to go to, attendance didn’t matter.

“I think I was one of the only kids that was really doing my work,” she said. “I kind of felt embarrassed.”

Some of Osife’s classmates would ask her for answers to the homework, but she usually declined. In the midst of the pandemic, educators expected grades to drop. The true effects of the lost educational year are hard to quantify, thanks to a pause in testing on the state level.

Superintendent of Public Instruction Elsie Arntzen helped to make the disbursement of the ESSER funds easier for schools. The money would be held as if it were a bank, where schools provided a list of their needs and the funds would then become available.

“We needed to make sure that our system was verifiable,” Arntzen said. “School districts can come in to say how they are allocating those dollars.”

Arntzen said a pause in state testing came when it became apparent that kids being in-person across the state could vary from district-to-district, school-to-school.

“If children are not in school taking tests, then the results were going to be very varied,” Arntzen said. “There would be very poor data, so we paused the tests — the federal government agreed to it.”

This school year, the Office of Public Instruction is focusing on assessing children with any test data they have.

But every district has a different test and different results, which means there’s no similar data points. Arntzen referred to the ability to compare them as “apples and oranges.”

***

Prior to the beginning of the 2020 school year, the Chromebooks finally arrived for the students of Lame Deer.

“We got every teacher doing online classes, every kid has a Chromebook,” Woods said. “For us that was a huge step, you know, one small step for the school and one giant step for the teachers.”

The laptops were supposed to be a light at the end of the tunnel, and for some students they were. But for some members of the staff, they showed a glaring gap in the faculty’s preparedness to teach online.

Sally King, an eighth grade science and English teacher, has been at Lame Deer for eight years. When the pandemic hit, she was worried how students who didn’t have the basic things to keep them safe — food, running water and electricity — would succeed away from in-person classes.

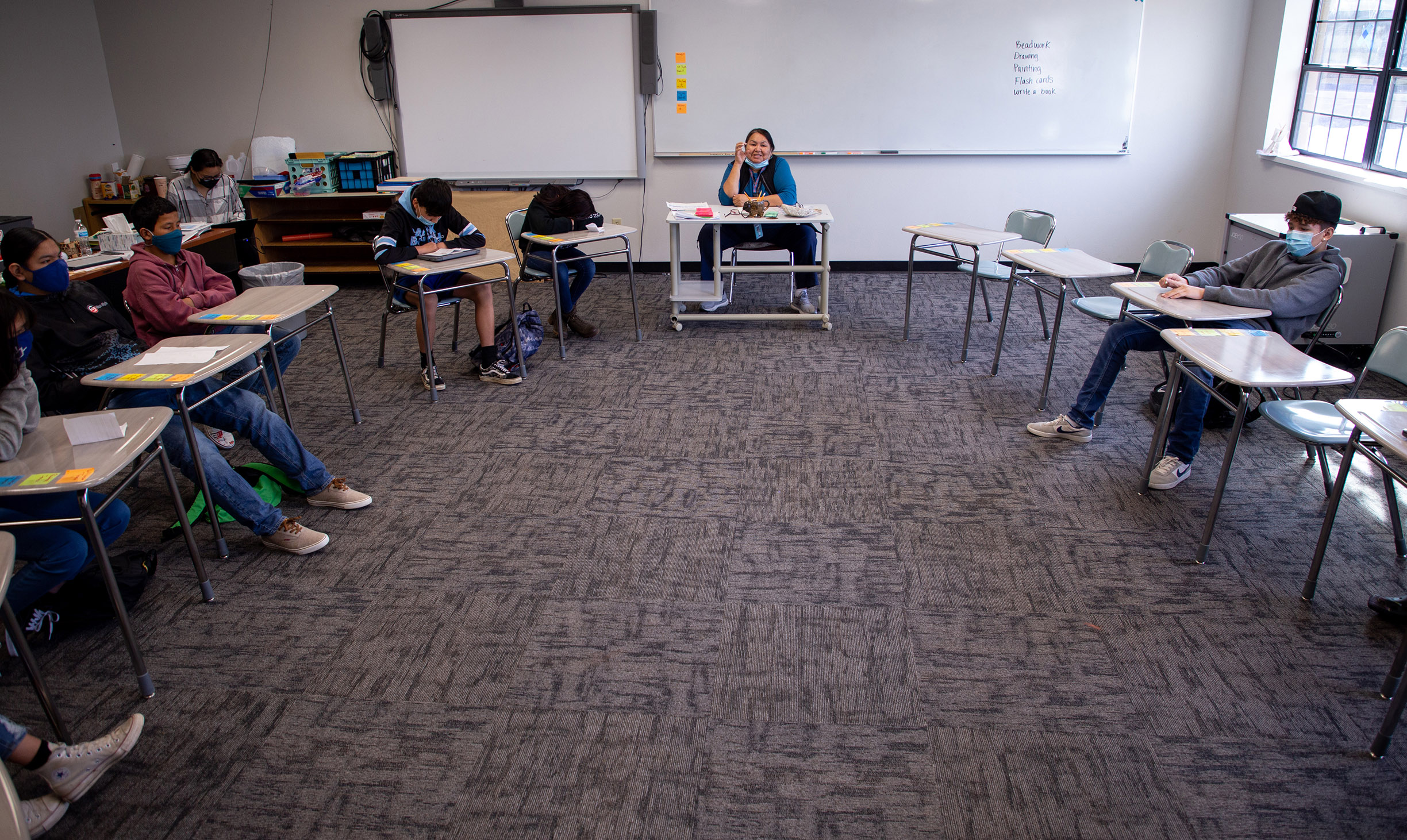

Enlarge

“My worry was for them, and how we were going to keep teaching them and having them still want to learn,” King said.

The arrival of the Chromebooks raised another concern for her.

“I had hoped our school would be more technologically advanced,” King said. “We just weren’t.”

Learning how to teach remotely was a task at first. Many of the teachers were older, and unfamiliar with using the laptops or Google Classroom. King said some were able to make the transition easily, while others struggled with learning the basics of the new technology.

By August, it appeared that school might be coming back, with the option for a hybrid model in the works. The decision to reopen was up to Woods. But then, athletic director and basketball coach August Scalpcane contracted COVID-19. Scalpcane had spent much of the summer interacting with kids, taking them boating, hiking — anything to get kids out from their homes. When the virus hit him, it hit hard.

Enlarge

Stories had been floating around about members of both the Crow and Northern Cheyenne tribes not coming home after seeking medical attention.

“I told my son, ‘Don’t let them take me to the hospital,’” Scalpcane said. “He says ‘Why?,’ ‘Because they haven’t been coming home.’”

It got so bad that Scalpcane had to be taken to the ER. He bounced from the IHS clinic on the Crow reservation to Billings, where he was nearly put on a ventilator.

Death came close for Scalpcane, with the doctor telling him his odds were 50/50.

“I had to tell him ‘I really don’t care if I make it or not. If I don’t make it I’ll be reunited with my son,’” Scalpcane said. “‘And if I do make it I’m blessed to stay here.’”

Scalpcane’s positive case led Woods to keep the doors of Lame Deer closed. But he kept fighting, and made it through.

The administration at Ashland Public School also dealt with COVID-19 on-staff. Principal and superintendent Courtney Small contracted the virus around the same time as Scalpcane.

“I was trying to be a principal from home,” Small said.

While her symptoms were not as severe as Scalpcane’s, the virus spread through her home. Her son tested positive, but remained asymptomatic.

“My 10-year-old son asked ‘Mom, am I going to die?’,” Small said.

Ashland Public, similar to Lame Deer, offered online-only classes at the start of the year. By Oct. 26, 2020, they opened the doors and installed a hybrid option, where some students worked from home and others came in-person. By March 2021, the hybrid option was still in play. However, only 14 of its 68 students were using the online option.

Ashland public used a portion of its CARES Act funding in a unique way to keep kids safe while in-person. Desks enclosed with Plexiglas, divided into four smaller “cubbies,” acted like individualized pods for the kids to work out of. The nearly 2-foot-wide workspaces featured whiteboards as the desk surface. These desks, which were once lab tables, were retrofitted in-house by the school’s maintenance staff. Each cost over $1,000 to produce.

***

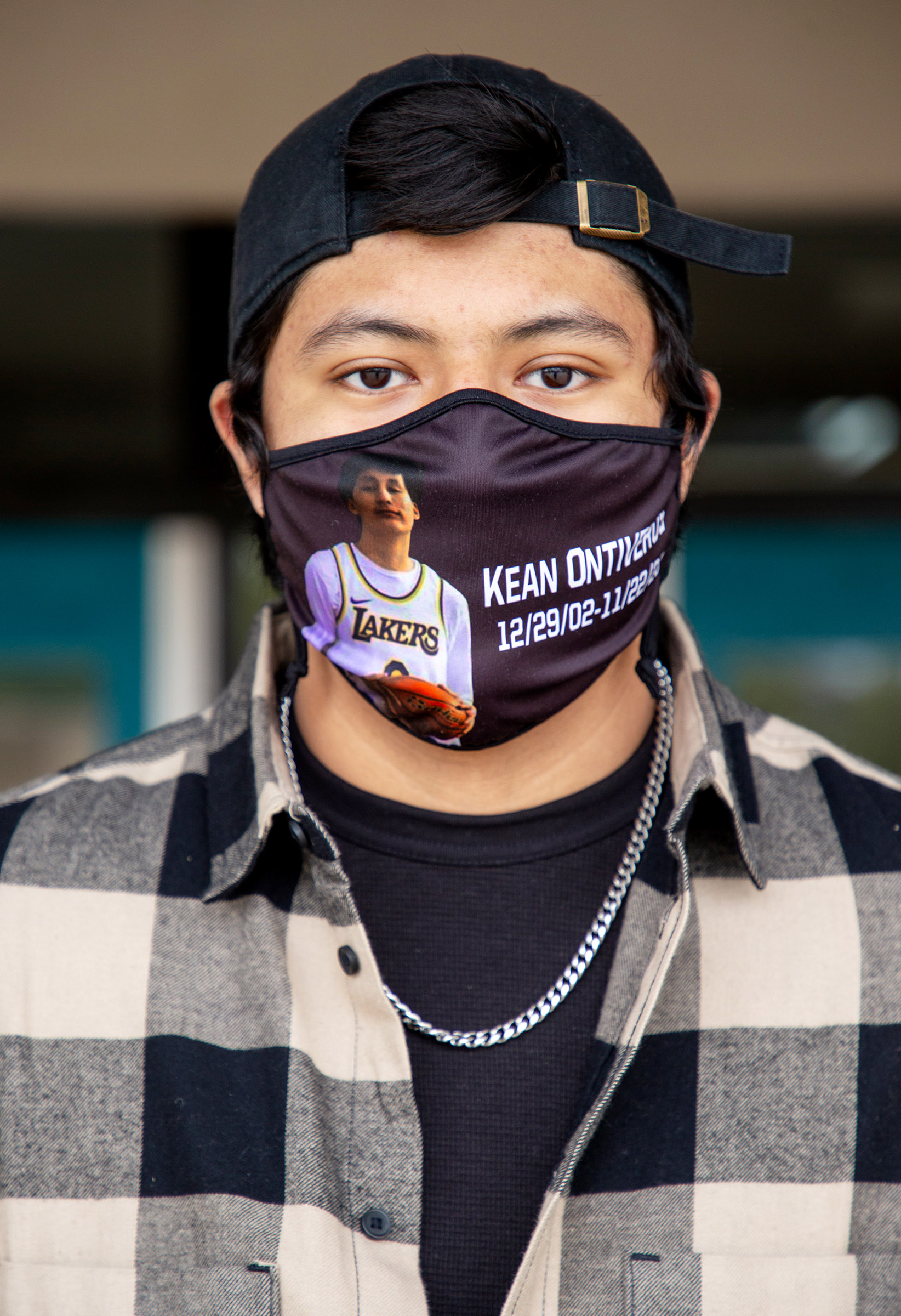

By October 2020, Scalpcane was eager to try and get kids back into school. But at this time, cases began to steadily increase on the reservation, and the death toll began to grow.

Four Lame Deer High School staff members passed away from the coronavirus.

For the staff and students left behind, picking up the pieces became all too familiar a practice.

The deaths of fellow staff members rocked counselor Betty Gion.

“In workplaces you become family,” she said. “It’s like that person at staff meetings always sat in that chair at the library. And it’s that empty chair.”

Enlarge

Gion has been a counselor at Lame Deer for over four years, and has worked in schools throughout Indian Country for over 20 years. Much of her time at Lame Deer had been spent helping students develop coping skills and deal with anxiety.

COVID-19 deaths in Lame Deer stayed low until November. Between then and February 2021, the death toll increased every day, with more and more elders slipping away. Many of the elders that passed were the ones raising students at Lame Deer. Some kids were not sure where they were going to live.

“When you lose elderly people, they are the rock of the family,” Gion said. “And probably the ones actually raising our students. And we had students that when that grandparent died, they had no place to go. That became really scary for them, you know, ‘Who’s going to take care of me?’”

Doney’s great uncle, who lived in Fort Belknap, passed away as well. She said he had been in the hospital for nearly four weeks.

“And next thing you know, he couldn’t take it no more. I was shook, COVID takes even healthy people,” she said. “It’s so random how it came.”

Doney contracted COVID-19 in the summer as well, but the only symptoms she experienced were loss of taste and smell.

Rosalie Birdwoman, a Cheyenne language and culture teacher at Lame Deer High School, with the help of Gion, sent out a message about grief and how to handle it.

“I know about grief, I’ve been a licensed addiction counselor for 31 years,” Birdwoman said. “I would tell them, ‘It’s normal, there’s nothing wrong with grieving. It’s part of life.’”

Her grandmother told her that the Cheyenne people, and everyone, should only grieve for four seasons, and when that year mark rolls around, they need to let that person go. She had heard many stories about people not being able to let go, where they would visit the graves of those they had lost and stayed overnight.

Enlarge

“What about your other kids? Other family members? That person is not the only one,” she said.

As the pandemic intensified on the reservation, Birdwoman turned to sweating to cope with the environment around her. People would join her, masked and maintaining their distance. Oftentimes, visitors would bring a spare mask for when the disposable ones became too sweat-soaked.

Heading into winter, she said that the death toll continued to rise. The bodies would go straight from the morgue to the graveyard.

That’s when she decided to write “Hard Times,” a poetic rumination on the challenges that come with loss and grief. The idea came from a conversation with an elder friend who likened the restrictions borne from the pandemic to those that prisoners face, shackled to a bench and kept hidden away behind windowless walls.

She wrote that what the Northern Cheyenne were experiencing was only temporary. Soon they would be able to return to normal, but first they had to survive the hard times.

***

Scalpcane wanted that return to normal more than anything for the kids at Lame Deer. His best bet was to open the basketball gym. In Indian Country, basketball is everything. He knew it would be difficult, especially as blame began to fall on the kids, with many labeling them as superspreaders.

He knew that they needed to walk first before they ran. The superintendent reached out and asked him if he thought they were losing connection with the kids.

“We ain’t losing them, we lost them,” Scalpcane said.

With help from Woods, Scalpcane opened the gym for a shootaround. He knew that being back on the court would become a magnetic force that drew kids back in. The Northern Cheyenne tribe ordered procedures be put in place to make sure kids were being socially distant and safe. At first he only allowed a couple students in at a time. But word spread and soon the gym was packed.

By November 2020, teachers began asking Woods and Scalpcane if students could come see them in their classrooms and get extra help. At first it was just at-risk students, the ones struggling with learning online, trickling into the classrooms. But that trickle turned into a river.

King said they had students scheduled Monday through Thursday to maintain social distancing. The magnetism of the classroom and school brought in more than she expected.

“Our classes would just get filled up, it looked like I had a full class walking down the hallway for lunch,” King said. “I feel like it is a safe, clean place for them, and it is something that they know.”

Enlarge

Nahshon Bighorn, a junior, was one of the students that came in for extra help. He transferred from St. Labre Indian School at the start of the school year. He came to Lame Deer High School to take advantage of its dual credit program, which allows students to attend Chief Dull Knife College while taking classes at the high school.

It was hard for him to get adjusted to being home all the time during the pandemic. His anxiety and depression became worse.

“Everything just got higher, it just seemed like I was more isolated, more alone, because I was just so used to seeing friends,” Bighorn said. “Being able to have these new opportunities at Lame Deer really helped.”

He began to fall behind in English while trying to catch up with his online work. But when students were allowed to come face-to-face, it helped him regain motivation. He said being able to get back into the classroom during that trial period really helped take pressure off of his shoulders.

“The thing I really like about Lame Deer is that it’s not just student-to-teacher, teacher-to-student, it’s like a family,” Bighorn said.

The great basketball experiment began. If they could have kids coming into the gym and into the classrooms, could they have a basketball season?

“I didn’t want to see the kids miss the season,” Woods said. “They deserve this. It felt almost like a punishment that they didn’t get to play.”

And so Scalpcane made the push to get the basketball season rolling. Some parents argued it was a bad idea, others supported it. The season would go on for both the boys and girls teams. It was rocky at first, with both teams struggling.

During the summer, Doney, like many of her friends, would still sneak off to hang out and see one another. During this time she said she slacked off on her training for basketball, opting to not go on runs and watch Netflix instead.

She came into the season out of shape, but by the end she made second team all-conference.

“When ball first started, it was everything,” Doney said. “We just all came together as a family.”

Before the pandemic, games at Lame Deer High School would typically sell out. The gym would be packed to the brim with eager, cheering fans. This year, all was quiet except for the sounds of rubber squeaking and pounding off the hardwood.

Bighorn, a center as well, reflected on the return of the season as something to look forward to.

“There’s the brotherhood of the team, but there’s also the love of the community behind us,” Bighorn said.

Scalpcane coached the girls team and had been with them since they were young. The start of the season was a struggle for Doney, with her numbers down and the team trying to find cohesion in their playing. Midway through the season, the boys coach quit. Scalpcane jumped over to their team, coaching them all the way to a dazzling five-point loss to defending state champions Lodge Grass.

Enlarge

“Once he left to coach the boys, we all just kind of fell apart,” Doney said.

The girls would face another detour in their season when a positive COVID-19 test quarantined the whole team. They were away from the gym for two weeks, but continued to work out to stay in-shape for the few remaining games. But then came a new head coach, a former assistant under Scalpcane who had worked with the girls throughout junior high.

With a new coach, Doney said everything turned around. They too made it to districts and battled against Lodge Grass, taking their rivals to double overtime but ultimately falling short. It was the only game they had that year with a loud and passionate crowd.

“Holy cow everyone was getting wild, especially that last overtime,” Doney said “Everyone was screaming.”

The experiment created by Scalpcane and Woods worked. They had a season without spreading COVID-19 throughout the school. The last time both teams had been together was during the season, now with the school reopening, everyone would be together.

***

Doney said she was nervous about coming back. Mostly because she was going to have to get used to waking up on time again. She, like Bighorn, is dual enrolled at Chief Dull Knife college. She spends the first part of her day there.

And on her full first day back at Lame Deer, she was sitting in her favorite place, the art room.

It was the first time she had been in that room since the pandemic hit. Art is her favorite subject, and one of the few items from her packet that she ever turned in. She was working on a print design for her graduation announcements.

It was her last first day.

Additional reporting by Hazel Cramer

Previous

Stopping the Leak