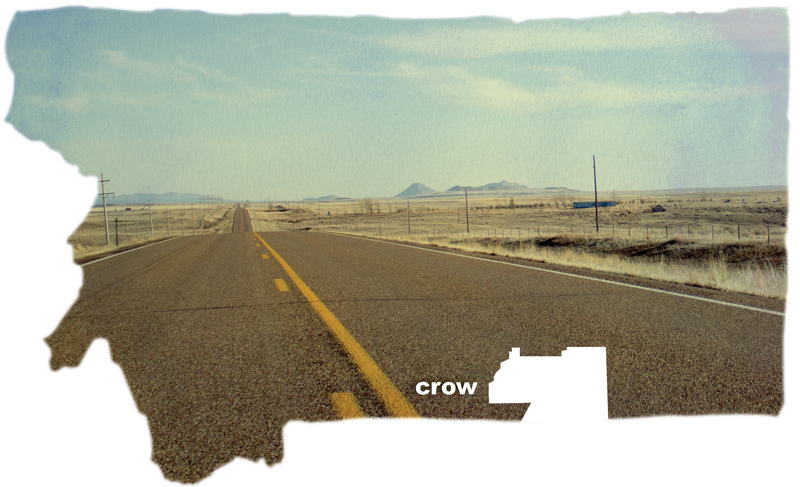

Crow

Crow – Waiting for Home

- Danny Plainfeather, 40, gives a tour of the land surrounding his family’s home. An offshoot of the Bozeman Trail ran through the property close to this area, known as the “chicken crossing,” and was a path for travelers centuries ago.

- Tessa Plainfeather and Emily Moccasin embrace in front of their grandmother’s home. Tessa and her parents live with her grandmother and uncle in separate homes on the same allotment of land.

- Mandy Plainfeather, 41, shows off an elk-ivory dress she made for her daughter in her home outside of Lodge Grass. Plainfeather said she likes the extra space her new home gives her for dressmaking.

- Danny and Mandy Plainfeather’s modular home outside of Lodge Grass. It took them three years to complete the Section 184 loan process and move into their home.

- Deana Laforge, 71, and her sister, Janice Medicine Horse, 56, in the yard of their apartment in the Apsaalooke Elders Program temporary housing. Laforge shares the two-bedroom apartment with anywhere from five to 12 people, depending on how many members of her extended family stay over.

- Deana Laforge, 71, sits in her apartment in the Apsaalooke Elders Program temporary housing. She has been on a waiting list to receive permanent housing for five years.

- Electrician Barry Glen, left, crew member Isaiah Dust, center, and head carpenter Chris Cole work on a house in Lodge Grass. As part of the renovation, the crew is making the house more handicap accessible for the elderly occupant.

- The unfinished wall of one of the Good Earth Lodges in Crow Agency.

- Items from the family living in this house are scattered in the yard. Housing authority workers remodeling this home in Lodge Grass said there were 31 people living on the property.

- The sun rises over the unfinished Good Earth Lodges in Crow Agency. The project on the Crow reservation was started in 2010 in conjunction with the University of Colorado-Boulder. The team developed large bricks made from materials found on the Crow reservation to build the houses.

- Nevaeh Fisher, 4, blows bubbles outside of her great-grandmother Elizabeth Stewart’s home in Crow Agency. Stewart secured the home through the Section 184 Indian Home Loan Guarantee Program.

- Juliette Fisher-Plain Bull fixes her daughter Nevaeh’s hair in front of their great-grandmother Elizabeth Stewart’s home in Crow Agency. Stewart obtained a Section 184 mortgage loan to finance her house instead of going through the housing authority.

Story by MATT HUDSON

Photographs by TIM GOESSMAN

It took three years of work for Mandy Plainfeather to secure her own home on the Crow reservation.

Three years for a process that required much more than just a nest egg and good credit. Instead, the Plainfeathers were bogged down by a stream of red tape mandated by the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs. Mandy Plainfeather, 41, had to gather about 20 signatures from government officials just to lay claim to a small portion of the rural trust land on which her family has lived for generations.

Mandy Plainfeather, 41, shows off an elk-ivory dress she made for her daughter in her home outside of Lodge Grass. Plainfeather said she likes the extra space her new home gives her for dressmaking.

The culmination came when the Plainfeathers—Mandy, her husband Danny, 40, and their three kids—moved into their house in 2008.

“I think all the stuff we went through just to get to this point, I was so used to trying to get more paperwork and more paperwork and more paperwork,” she said. “So when this house came, to me it was just kind of unbelievable. This has been a lifelong dream for me.”

She is among a first generation of enrolled Crow members to independently finance their own homes on the reservation. Until recently, tribal citizens relied on the local housing authority, which has struggled to keep up with the increasing housing demand.

But financing a home on trust property also means dealing with the strict federal oversight. If something is to be built, it must be federally approved through a process that is daunting and time consuming.

“It’s a lot of paperwork,” said Crow Chairman Darrin Old Coyote. “A lot of people, halfway through the paperwork, say, ‘Heck with this,’ and basically give up on pursuing a loan because of all the paperwork involved.”

For more than a century, the treaties between Native Americans and the U.S. government that promised sovereignty and support for the Crow also created a barrier to true home ownership.

“Even though we’re within the United States of America, we’re still like a foreign country,” Plainfeather said. “That’s why you hardly see any kind of major developments, because we have to go through the BIA. And once they say yes, then you can do certain things, like this house.”

Tessa Plainfeather and Emily Moccasin embrace in front of their grandmother’s home. Tessa and her parents live with her grandmother and uncle in separate homes on the same allotment of land.

The main reason it’s difficult to put a home on the reservation is because the federal government holds the land in trust, meaning it holds the title to the physical acreage on behalf of the tribe. It’s the result of the federal policies formed more than a century ago, leaving intricate land ownership issues and a checkerboard of tribal and non-tribal land.

Because the tribal and individual allotments are held in trust by the federal government, the Bureau of Indian Affairs must approve land-leasing deals. That includes placing homes on trust land.

And because the federal government has primacy over land usage, Native Americans often could not use their trust land as a security for a standard mortgage loan.

“The local banks wouldn’t loan to tribal members in some cases,” Old Coyote said.

Banks are particularly hesitant to loan to tribal members living on trust land because the jurisdiction boundaries when it comes to collecting on defaulted accounts are, at best, hazy. In the past, he said, the loan programs available often came with interest rates so high that people ended up selling their homes to escape the debt.

“Predatory lenders were a big thing on the reservation if you wanted [to own] a home,” Old Coyote said. “You’d get anywhere from 6 percent and up.”

Most Crow tribal members lease housing through the reservation’s housing authority, an extension of the tribal government. Tenants can rent units or pay one off over the course of up to 30 years. But with the limited funding and a growing number of tribal members needing housing, it has struggled to mediate the reservation’s housing issues, which include overcrowded units, long waiting lists and substandard living conditions.

“These homes are falling apart faster than we can maintain them,” Old Coyote said. “A lot of these homes are falling apart even though we throw money at them. They’re still falling apart because they weren’t built up to standard, up to code.”

Danny Plainfeather, 40, gives a tour of the land surrounding his family’s home. An offshoot of the Bozeman Trail ran through the property close to this area, known as the “chicken crossing,” and was a path for travelers centuries ago.

When Plainfeather and her husband wanted a home, they looked for a way around the housing authority’s waiting list. But on trust land, there is no circumventing federal oversight.

They found a program that landed them in their own home, but not before a lengthy process requiring the coordination of the tribal government, her bank and the BIA.

Plainfeather applied for a mortgage loan through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Section 184 Indian Home Loan Guarantee Program. Implemented in 1992, it was designed to increase the willingness of lenders to work with trust allottees. HUD guarantees the loan for the lender in the event of a default.

Plainfeather’s lender was a Wells Fargo branch in Sioux Falls, S.D., which has an office for Native American lending. While not all banks are trained for lending on trust property, the branch has adapted to serve this niche for clients on reservation lands and throughout the country.

Juel Burnette, the branch’s sales manager, said that on non-tribal land, they can close a traditional home mortgage in 30 to 45 days. For a Section 184 loan, the land survey alone usually takes longer than that.

“We’re waiting a minimum of 60 days just to get the land info back from the Bureau of Indian Affairs,” he said.

Plainfeather took the first step toward homeownership in 2005 when she filed with the BIA to receive a 2.5-acre plot from her mother.

Then the BIA handed her a list of right of ways that needed to be approved. To clear the gravel road from the highway to her house, she had to file three right of ways through fee land and separate trust allotments. The right of way for her electrical service came with a $2,200 bill for a new utility pole. On the rural, checker-boarded landscape of the Crow reservation, this is a common occurrence.

To be able to put a house on trust land, Plainfeather had to obtain a home-site lease. For this, the BIA performs surveys, including land appraisals, checking for cultural or historical significance and examining the environmental impact of development. The paperwork travels through the tribal administration building, the local BIA realty office in Crow Agency and the regional BIA office in Billings for separate approvals. Depending on the capacity of each office, the forms can get bottlenecked. Some homeowners claimed the BIA lost their paperwork multiple times during the process.

Items from the family living in this house are scattered in the yard. Housing authority workers remodeling this home in Lodge Grass said there were 31 people living on the property.

Plainfeather said she collected about 20 signatures in all, from the BIA, the Crow tribal government and the bank. At times, she had to show up at people’s offices to get them to sign, sometimes more than once.

“It was basically the same people to get those signatures,” Plainfeather said. “Well, they didn’t tell me that until after each one.”

The BIA performed surveys of four different sections of her plot, because they found high water tables on the first three. It was a headache for Plainfeather, but she is thankful it didn’t take longer.

“Some people wait for home site leases for years,” Plainfeather said.

One of the major complications with obtaining home-site leases is the fractionation of trust land. After more than a century of reservation allotment, the increasing number of heirs to individual allotments has made claiming a trust plot difficult for one person. An allotment could have more than 100 heirs in some cases. If one of them decides to put a house on that land, they need to get signatures from a majority of the heirs.

Plainfeather only needed the signature of her mother, who was the individual holder of the land allotment.

In 2007, Plainfeather and her husband began searching for the perfect house while the BIA finished its work. After being pre-approved with the bank for their Section 184 loan, they had an idea of how much they could spend.

“I wanted a home that was going to last us, like, five generations because, you know, this is our home and it’s always going to be our home,” Plainfeather said. “And that my kids, my grandkids, have a place to come home to.”

She closed her loan with Wells Fargo in November 2007. They also received $10,000 in down payment assistance through a program with the housing authority. Immediately her husband, who has construction experience, began work with their son and nephew to build the foundation. The house was delivered on Valentine’s Day. The family moved in May 2008, nearly three years after she filed the first set of paperwork.

Nevaeh Fisher, 4, blows bubbles outside of her great-grandmother Elizabeth Stewart’s home in Crow Agency. Stewart secured the home through the Section 184 Indian Home Loan Guarantee Program.

Burnette said lending on the Crow reservation is uncommon because in addition to the BIA, a tribal economic development administrator must also approve certain land lease transactions, adding another link to the chain.

That job rests with Shawn Real Bird. He knows a bit about Section 184 loans, because he helped bring it to the Crow.

When Real Bird was 13, he went with his grandfather to Billings to replace their old Dodge pickup. He said his grandfather brought documents to the dealership that showed a good income from tribal land leasing. They bargained until it was nearly closing time, until the dealer told them they couldn’t buy the pickup because the dealership could not verify the leasing income.

Distraught, they returned to Real Bird’s hometown of Garryowen on the reservation. Later, Real Bird’s father told him that because they are Native American, “their money is not as green as the rest of the U.S. citizens.”

That idea affected him. That night he prayed he could help change that.

“I said to the Creator, ‘Let me understand how this financial system works, this money system. I’m going to help my people that way,’” he said.

Real Bird, 49, works as the Crow tribal economic development specialist, but before that he was a realtor based out of Billings. Two of his real estate clients, a couple working for the Indian Health Service, wanted to purchase a log cabin overlooking the Little Big Horn River. The couple met the credit requirements. They had a combined six-figure income and were pre-qualified for a mortgage loan.

Still, the underwriters denied the couple’s loan application. The realty manager told Real Bird that the Crow lacked the legal infrastructure, an official foreclosure procedure, to support lending on trust land.

“She said, ‘How could it be in the 21st century that individuals don’t have the right to obtain financing, live that dream? That all-American dream?’” Real Bird said of the conversation with his manager.

The realty firm manager told him that the Crow were unable to finance their homes because of the trust status of their land. Real Bird recalled that day with his grandfather.

“I remembered that prayer a long time ago,” he said. “It’s coming full circle now.”

Armed with a master’s degree in community economic development, Real Bird went to work for the Crow tribe with his IHS clients in mind. In 2003, he started work in the economic development department. He had learned about the Section 184 loan program and wanted the Crow to be eligible. To qualify, tribes must develop trust land leasing and foreclosure protocols. He worked with attorneys from a Billings bank and the Crow administration to draft those procedures. An important provision of the Section 184 loan rider for Real Bird was that, in the event of a foreclosure, the land stays within the tribe.

“If an enrolled member goes into default, the only alternative buyers would be the Crow tribe, an enrolled member of the Crow tribe, or an organization of the Crow tribe,” Real Bird said. “And that way, it keeps its trust status.”

HUD and the Crow Legislature approved Real Bird’s revised legal procedures in 2004. Since then, he said he has helped 160 families get loans.

He said the program helps Crow members see financial independence and allows them to dream big about where they want to live. He wants them to know that tribally sponsored housing is not the only option.

The Apsaalooke Nation Housing Authority is headquartered in the town of Crow Agency. The small town surrounds the Little Big Horn River and borders the Little Big Horn Battlefield National Monument, the site of Gen. George Custer’s famous last stand.

Electrician Barry Glen, left, crew member Isaiah Dust, center, and head carpenter Chris Cole work on a house in Lodge Grass. As part of the renovation, the crew is making the house more handicap accessible for the elderly occupant.

The housing authority operates on a block grant from HUD and serves three-quarters of the housing on the Crow reservation, according to its executive director, Karl Little Owl. In 2012, their budget was just over $3 million. That pays for about 50 employees and goes toward building new homes and renovating existing models.

The housing authority offers low-rent units or mutual-help-leased homes for tribal members. The monthly payment on a low-rent unit is determined by an individual’s income. The mutual-help leases run for up to 30 years, and if the lease is completed, it is turned over to the tenant. They share the cost of repairs and appliance replacements throughout the lease period.

However, the need for housing outweighs what the housing authority can provide.

Michelle Wilson, the administrative officer for the housing authority, said their resources have decreased in recent years. She said development is now at a standstill and the authority can only meet one-third of the reservation’s current housing needs.

“We’re not building new homes,” she said. “We don’t have any new homes available.”

A 2012 study by the University of Colorado-Boulder estimated a backlog of 1,500 housing applications at the Crow housing authority. With nowhere else to go, families often move in with other families, leading to overcrowded units. Old Coyote said it’s common for two or three families to share a small house built for a single family. This contributes to what he calls an “invisible homeless” population.

Wilson said the new tribal administration has made it a priority to address the housing disparity. The housing authority is becoming stricter with tenants who fail to make their payments. She said their funding depends on how closely they follow federal regulations and that previously, payment schedules were loosely enforced. The result was a decrease in housing grants.

In April, Wilson was preparing to send out 100 compliance forms, requiring delinquent tenants to agree to get back on track. If they don’t agree, they will be evicted.

Enforcing lease agreements is not an easy job but a necessary one, Wilson said. If tenants comply, the housing authority’s funding could increase and more needs could be met.

“They need a better standard of living, and in order to do that, it takes funding to be able to renovate these homes and make the upgrades that are necessary and provide homes that are really in dire need,” she said.

Plainfeather’s 2,000 square-foot modular home looks unassuming from the highway, across a quarter-mile stretch of field where the family’s horses graze. Inside, tall cupboards reach up to the high, slanted ceiling in Plainfeather’s kitchen. Three ovens are mounted in the wall at the end of the counter. She planned it that way, they are her favorite commodities in the house.

She also planned how the house is situated, for a perfect view from the kitchen table. In front, the window frames the snow-capped mountains. To the left, she can see her horses in the field and the rolling hills leading eastward to the town of Lodge Grass. To the right is the family den and the bedrooms of the couple’s children. A sewing machine sits on the dining room table next to the intricate dresses Plainfether made for her daughters.

Toward the south end of the larger family plot runs a rutted dirt trail that crosses a quiet creek and leads into the hills, a path called the “chicken crossing.” She said that’s where travelers made their way to and from the famed Bozeman Trail for centuries. Today, Plainfeather and her husband, Danny, lead their cattle on horseback to graze over that same path.

Danny and Mandy Plainfeather’s modular home outside of Lodge Grass. It took them three years to complete the Section 184 loan process and move into their home.

Plainfeather has a deep respect for the property, which has stayed with the family. Her uncle lives in a cabin nearby, and her mother’s house is there. Plainfeather planned for a long time to have her own place on the allotment.

Plainfeather likes to have family functions at their house, using her three ovens to prepare large meals. She and her husband feel they are finally settled down, in their 10th year of marriage.

They have horses and cattle, with three calves on the way. They’ve built two sweat lodges in the tranquil area near the creek. One is housed in a wooden shed for winter use. The other is a stick frame with no covering, awaiting use in the summer. It’s a sign of permanence, a sign that they anticipate a long future on this plot. Plainfeather is proud to live where her family does and that she helped create this life for her family. It’s the kind of vision Real Bird has for Crow homeowners.

“It gives them ownership in this property, and I believe that ownership eliminates social problems, personal problems,” Real Bird said. “If a husband and wife have a home, and their children can be someplace and they can own things and they can have different Native American ceremonies on that trust property, picnics, invite their families, have birthday parties, then they have a healthy lifestyle.”

Both Old Coyote and Real Bird proudly say they are among the first generation of Crows to take that initiative and own homes independently on the reservation.

Plainfeather is among them. She lives in the result of her ambition. She doesn’t have to live away from her family’s allotment in a housing authority unit. She doesn’t have to sit on a waiting list, hoping one of the two repair crews that serve the 2.2 million acres of the Crow reservation will stop by.

Those duties are her own. Her house is her own. She’s living that American dream.

Native News Project 2013

Native News Project 2013