Photos by

Russel Daniels

(Click to view gallery)

Information

Name: Blackfeet

Tribe: Blackfeet

Population: 10,100

Native: 91%

Counties: Rosebud,

Big Horn

Safe Keeping

On the Blackfeet Reservation, the Po'ka Ranch looks beyond bars and walls to help troubled youth.

Written by Chris Arneson

The big brown building on the outskirts of Browning on the Blackfeet Reservation stands next to a picturesque red barn. It doesn't look like a juvenile justice facility. There are no bars and no police officers. The scene might fit better on the pages of a children's book, except the children that it shelters have endured less than a storybook life.

Inside the house dozens of children down steaming bean soup, anxious to get outside where they can play and ride horses. Once dinner's done, the kids run hollering and laughing out the front door, past the barn and the silhouettes of jumping sheep, cows, cowboys and horses that are painted on its side. Staffers smile as they approach with horses already saddled.

Back inside children color pictures of elk, or ponoka in their native language. Floyd Heavy Runner tells them the Blackfeet names of deer and bear. In Blackfeet the ranch's name, po'ka, means child, Heavy Runner says, explaining that the "p" takes a "pb" sound. Heavy Runner, whom the kids call "Tiny Man," is one of few tribal members who still speak the language fluently.

The Po'ka Ranch is the Blackfeet tribe's most recent attempt at combating juvenile delinquency. It fuses Blackfeet culture with incentivebased prevention and education programs to rehabilitate high-risk children at the first sign of trouble. Though the program is still developing and has only been taking clients since November, it represents a glimmer of hope on a reservation with a troubled history in juvenile justice.

Each day after school lets out, Browning school bus No. 5 fills with children headed to the Po'ka Ranch. It carries them through downtown Browning, past the town's only grocery store and past the bright lights and crowded parking lot of the Glacier Peaks Casino. The bus squeals to a stop at the old homestead, just out of sight of the boarded-up windows and abandoned cars that litter the small town.

Each of the more than 30 children who step off the bus have some "need" that has been identified by a staff member.

"It might be that they're behind in school, it might be they're in foster care, it might be that they have a death in their family," says Po'ka executive director Francis Onstad. Sometimes children are admitted because they abuse drugs or alcohol. Program staff only have to identify one "need" to admit a child. And once enrolled in the program, a child's family and siblings are encouraged to take part in activities, celebrations and counseling.

Although Po'ka has about 70 clients, it provides services to more than 100 people, counting family and siblings. All of the clients are there by choice. Free food and activities help to keep them coming back every weekday and children and parents alike are drawn to the culture-centric curriculum.

After a hot meal and a few hours of horseback riding, language lessons, or life skills classes, staff round up the children at the Po'ka Ranch and herd them into white 15-seat vans, and deliver them to their homes. But the learning doesn't stop there. Heavy Runner has recorded hundreds of Blackfeet phrases into Phraselator language software. Children and families can check out a computer from Po'ka to practice the language at home. They can also take home LeapFrog educational software, which Po'ka uses to improve reading and writing skills for children who may be behind in school.

Po'ka is funded by a slice of a $9.5 million federal grant intended specifically for Indian country that requires Native American culture be integrated into every aspect of the program. It mandates that Po'ka incorporate a child's family in the rehabilitation process. This is a radical departure from earlier Blackfeet juvenile justice efforts that focused little on rehabilitation, and often took the form of week-long stays in the reservation's juvenile detention facility.

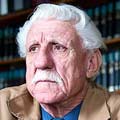

Ben Yellow Owl remembers what things were like before Po'ka. He works on the ranch now — sometimes in the kitchen, sometimes with horses. Wherever he's needed.

He's wearing a stained, gray sweatshirt with blue cuffs that match the color of his faded jeans, marked by an oil stain just above the right knee. In his arms he holds a child with dark curly hair and a curious smile. Bright brown eyes look up at Yellow Owl as he takes off his baseball cap, and introduces himself.

"I'm Benjamin Ray Yellow Owl. I'm 17. I'm a dropout, a teen parent, and this is my first child, Bryson Benjamin Alexander."