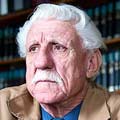

Photos by

Russel Daniels

(Click to view gallery)

Information

Name: Blackfeet

Tribe: Blackfeet

Population: 10,100

Native: 91%

Counties: Rosebud,

Big Horn

"Sometimes they'll transport two or three times a night," says Tribal Judge Don Sollars. "It's just such a waste of taxpayers' money. It seems to me that for what the bureau is paying to transport these kids, they could build a facility."

When youth are released from the Busby facilities, the BIA doesn't drive them back to the reservation. Instead, parents have to make the eight-hour trip to retrieve their children.

"Not everybody has the money to run and get 'em," Sollars says. " A lot of times they'll have to borrow money to go get 'em, and I think that's wrong."

The Tribal Council and juvenile justice system are working to reopen the White Buffalo Home on a limited basis, and they're also lobbying the federal government for money to build a new juvenile detention facility. So for now, judges and prosecutors are wary of imposing jail time for minor offenses. They're more likely to sentence a juvenile to house arrest, probation or drug treatment classes than a jail stay in Busby.

Officials say reopening the White Buffalo Home would be something of "Band-Aid." What the tribe really needs, they emphasize, is a new juvenile detention center that is adequately funded and staffed with trained therapists and correctional officers.

Tribal officials remember all too well the history of the White Buffalo Home. They remember the congressional hearings and FBI investigations into abuse. Echoes still reverberate down the hallways of the old building when doors of cells, now used for storage, slam shut. And horror stories still send shivers down the spines of former White Buffalo employees.

In 2003 the BIA assumed control of tribal law enforcement responsibilities, including the White Buffalo Home. Law enforcement officials say juvenile crime rates soon jumped on the reservation. At White Buffalo, reports of abuse began to surface. A 2004 congressional investigation noted that a White Buffalo employee had been charged with raping a 17-year-old inmate while transporting her to the hospital.

Corrections officers at the home also made extensive use of what they called the "resister chair." Unruly kids were shackled to the chair, then hooded and left for hours or even days on end, former tribal Police Chief Fred Guardipee says. The Tribal Council outlawed the practice in 2004, but not before the device left psychological marks on young Blackfeet children.

Guardipee was on the Tribal Business Council's law and order committee, which in theory had oversight of White Buffalo. He says simply locking children in a jail cell does little to deter them from reoffending.

"It was a real form of punishment," Guardipee says. "Everything was a form of punishment; rather than looking at trying to rehabilitate our children, we were punishing them. And our children were being made (into) criminals."

Freda Vielle was a correctional officer at the White Buffalo Home before it closed. She says most staff tried to improve the lives of kids who ended up there. The staff therapist helped with homework and conducted counseling sessions for the young inmates. But the facility was underfunded, overcrowded and did little to keep kids out of trouble.

"I don't think it helped them," Vielle says, while showing visitors through the old facility. "A lot of them were depressed being in here. They were always wanting to get out."

The home's biggest failure, she says, was that it didn't incorporate parents into the healing process. On the reservation, family can offer the moral support of hundreds of cousins, aunts and uncles. But when the family isn't there to stand behind a child, it can be devastating.

"I witnessed a lot of parents calling up here and saying, 'Oh, just keep my kid in there,'" Vielle says. "Parents wouldn't even want to come see 'em. It made them feel unwanted."