|

Pride and Prejudice

Prejudice and stereotypes

often confront

Indians who move off the reservation

Story by Katie Oyan

Photos by Amy Zekos

Twelve-year-old

Mandi Henderson likes Washington Middle School because of the

opportunities it yields, like being able to play the cello in

the school's orchestra.

What she says she doesn't like is being called a "dirty

Indian" and a "prairie nigger," and told that

she doesn't "belong on this earth."

She moved to Missoula from the Blackfeet Reservation two years

ago, and what Mandi says she misses most is "being around

people that are like me."

"There's more stuff to do here," she says. "But

I don't get treated bad in Browning."

Whether it's in-your-face name calling or more subtle forms

of discrimination encountered when trying to rent a house or

get a loan, Montana's Native Americans, who comprise more than

6 percent of the state's population, routinely suffer the humiliation

of racism.

Mandi's mother, Glenda Gilham, will graduate from the University

of Montana with a degree in social anthropology this spring.

Like her daughter, Gilham has few non-Indian friends in Missoula.

She feels comfortable going anywhere she wants on the reservation,

but she and her two daughters don't go out on the town much in

Missoula; they rarely go to movies or out to dinner because of

discrimination they say pervades much of the city.

"It's subtle things - how we get looked at and spoken

to, or not spoken to," she says. "Sometimes we just

get outright ignored.

"We feel alone and apart from society in Missoula. I never

realized how bad it was until I had to leave my comfort zone."

Gilham and other members of Missoula's Indian community feel

that business owners, especially, label them with stereotypes.

They say that clerks watch Indians because they believe they

are more likely to shoplift.

Janet

Robideaux, an organizer at Missoula's Indian People's Action,

says: "Nobody looks at me and says, 'I bet that she has

a master's degree in psychology.' They look at me like I'm going

to take something. They see brown skin."

Gilham has the same reaction. "When we go shopping somewhere,

why do they follow us so much?" she asks. "We contribute

a lot to these communities in Montana. Nobody stays home when

they get paid, they all head out and blow their money, but yet

we're treated so low."

While shopping at J.C. Penney in Missoula's Southgate Mall

about a year ago, former Big Pine Paiute tribal chairwoman Cheryl

Smoker says a clerk asked her, "Can you really afford this?"

Rob Kruckenberg has been the manager at J.C. Penney since February,

and he says there have been no discrimination complaints during

that time.

"We don't discriminate in terms of employment or service

on race, creed, religion, you name it," Kruckenberg says.

"We have a strong anti-discrimination policy, and all our

employees go through anti-discrimination training."

Gilham says her encounters with racism are not confined to

Missoula. Three years ago she tried to rent a motel room in Great

Falls. The vacancy sign was on, she says, but when she went inside,

the woman at the counter told her no rooms were available. Her

husband, Oren, who is half Blackfeet and Cree and half Irish

descent and is more non-Indian in appearance, went into the motel

immediately after Gilham was rejected. The clerk rented him a

room.

That's not unusual, Native Americans report, though few confront

those they say offend them. Cheryl Smoker has.

Smoker moved to Missoula from the Big Pine Reservation in

California more than three years ago with her two daughters,

Kree, 7, and Kylee, 14, and her mother. They say that since the

move they have encountered discrimination not only at businesses,

but also at a school and from police officers.

Smoker says Washington Middle School ignored her family's

cultural values during a period when Kylee was very ill. She

says the school excused absences when Kylee went to see a doctor

and was hospitalized, but would not excuse absences to let her

see a traditional healer. According to Smoker, a school counselor

told her that since Kylee already had too many absences, Smoker

would be prosecuted for taking her daughter out of class to see

a healer.

But a Washington School counselor expressed surprise at those

allegations.

"I can't imagine that would be the case," says Carol

Marino.

Marino says such absences are normally considered medical appointments,

and as long as a parent calls or sends a note, the child will

be excused.

"But there are kids who miss a lot of school that we

watch very carefully," she says.

Never having lived off the reservation before, Kylee had difficulty

adjusting. In addition to problems with her school, during her

first year in Missoula, Kylee, who normally dresses in Nike clothes

and baggy pants, says she was stopped by a police officer and

asked what gang she belonged to.

The incident occurred at about 8 p.m. one night a couple of

years ago, Kylee says, while she was playing basketball with

some Native American friends at a neighborhood court. Kylee says

the policeman stopped and asked them what gang they belonged

to and whether they were "going to rob again." Kylee

and her friends denied being part of a gang, and the officer

left, she says.

"They didn't have any proof," Kylee says. "I

felt really insulted."

Kylee and her mother, and several people who spoke at a recent

meeting between the city police and the Indian People's Action

(IPA) allege Native American youths have been targeted by cops

as being gang members.

Missoula

Police Chief Pete Lawrenson says he believes the complaints made

at the meeting were not entirely unfounded, but he doesn't think

his officers intentionally discriminate against anyone.

"Kids and cops always have an adversarial role, whether

they're Native American or any ethnic group," Lawrenson

says. "We have to be extremely aware of how easy it is to

be discriminatory against young people in general, regardless

of ethnicity."

Part of the problem, IPA members say, is that there are no

Indians on the Missoula police force.

Gale Albert, head of recruitment for the Missoula police department,

says there is no discrimination in the process of hiring officers,

but few minorities show up for testing.

Many Native Americans are hesitant to apply for municipal

and police positions because they don't feel they have a chance,

according to Ken Toole, program director of the Montana Human

Rights Network. Toole feels this is due to low self-esteem that

comes from a lifetime of rejection and discrimination. Also,

Toole says that Native Americans receive the message that people

in city positions are among those who discriminate against them,

and "Who wants to work with people who have stereotypes?"

Albert says Native Americans have no basis for such assumptions.

However, Robideaux says, "the word on the street is if you're

Indian, don't bother applying."

According to Lawrenson, the Missoula Police Department is

serious about recruitment efforts and bridging the gap between

the force and the Native American community.

"We're not just blowing smoke at them," Lawrenson

says. "We're as serious as we can be about this.

"We've written to all seven tribal colleges and asked

to participate in their career fairs. We want build the confidence

and trust that we'll give them a chance. Recruitment will come

naturally as we build the confidence level."

Lawrenson is also organizing diversity training courses with

IPA for police supervisors and officers, to begin possibly as

soon as September.

After problems with her school and the incident with the police,

Kylee packed up and returned to California to live with her father.

"That was probably the hardest time for me because we'd

never been apart," Smoker says. "It made me mad. I

felt like the city was not kind. Missoula took her away from

me."

Kylee came back to Missoula to live with her mother, but she

now commutes daily 100 miles round-trip by bus to Two River Eagle

School in Pablo, a tribal-operated school comprised entirely

of Indian students.

Unlike many Native Americans who return to reservations after

facing discrimination in cities, Smoker and Gilham have stuck

around.

"We have a right to be here," Smoker says.

Racism

that goes beyond name-calling and stereotypes can be harder to

shrug off.

In a test for discrimination in Great Falls housing in the

late 1980s, more than 50 percent of the Indians who participated

were treated differently by landlords than were whites. They

were asked to pay higher rents and deposits, and given limitations

not placed on other tenants, such as being allowed to have only

one car, and being warned not to crowd the house by letting extended

families move in.

Les Stevenson, executive director of Opportunities Inc. in

Great Falls has seen positive changes in his community since

that study. He feels that some forms of discrimination, like

in housing, have decreased due to a citizens' committee, the

Indian Action Council. Comprised of city officials and Native

American community leaders, the committee opened communication

and addressed sensitivity issues that had been ignored during

the 1960s through the 1980s. Although it didn't completely eliminate

the problem, an effort was made to educate the business community

that "just because they're Native American doesn't mean

they're a thief," he says.

Great Falls now has a fair housing officer and a landlord

association striving to maintain consistent deposits and applications.

A Realtors association is helping Indians in Great Falls become

homeowners.

However, critics say they fear housing discrimination in getting

worse statewide.

The number of complaints filed by Native Americans with Montana

Fair Housing almost doubled (from 37 in 1996 to 69 in 1997) in

the last year, according to Executive Director Sue Fifield. She

says a majority of these complaints came from urban areas near

reservations, such as Missoula, Great Falls and Billings. Fifield

expects these numbers to continue to increase.

Toole believes the numbers are higher than reported.

"You have to be careful when you look at statistical

analysis of complaints," Toole says. "A lot doesn't

get reported, because many times the victim doesn't know they've

been discriminated against."

This occurs when an Indian wants to rent a home, and the landlord

claims it has already been taken, or when the application process

or deposit is different, and the Indian applicant has no way

of knowing.

Assuming the victim is aware of discrimination, Toole says that

because the process of filing a complaint is intimidating and

time-consuming, many victims are not willing to take their complaints

to a formal level.

A contributing factor to the problem lies in Native American

upbringing.

"They're not from a cultural background that encourages

them to get involved with the legal process," Toole says.

"It can be confrontational and accusatory, and that's not

the Indian way of doing things."

Robideaux says that like many Native Americans, she was raised

traditionally to be soft-spoken. As a youth, her grandfather

taught her to take pity on racists.

"But I'm tired of setting the example; I want people

to get this," she says.

An example of the type of complaints that comprise the Montana

Fair Housing statistics is a 1994 case in which Richard and Donald

Lee, owners of Lee Apartments in Billings, were accused of discriminating

against Native Americans by denying them apartments based on

their race and national origin.

The case ended with the Lees paying a total settlement of

$65,000, which was divided among the 12 individuals who filed

complaints, a now-defunct group called the Concerned Citizens

Coalition and the United States government.

"You can't defend yourself against someone when they

do that to you," says Donald Lee, who was born and raised

on a reservation and says he had many Indian friends and never

discriminated against them.

"There were 36 government people working on the case,"

he says. "And they coached the testers on what to say."

Lee says his attorney told him he could prove Lee didn't discriminate,

but taking the case to court would cost around $100,000.

"We settled out of court because the debt was so high

we couldn't afford to defend ourselves," he says.

Lee says, however, that he was constantly filing complaints

with the police because of the unruly behavior of Native Americans

who lived in his apartments.

"My brother told one of the Indians, 'You fellows get

your money from the government and you go to the Lobby Lounge

and get drunk and come over and pee in the halls and poop in

the halls.'"

"But we rent to anybody now," he says. "We're

afraid not to."

Robideaux thinks that one of the causes of discrimination

is a lack of education about Indian people.

"We're almost to the new millennium and we still have people who believe we get that government check every month," Robideaux says.

"Unless people stop believing that, discrimination will

continue."

Wyman McDonald, Montana's coordinator for Indian Affairs, believes

this problem begins in the state's public education system. He

says children should be taught Native American history, so that

both Indians and non-Indians can develop an understanding and

appreciation of Indian culture. Indian children should not be

left on their own to find out about it, he says.

"Government classes start in about fifth grade or so,

and they express negatively what tribal governments are doing,"

he says. According to McDonald, the negative impression and criticism

Indian children get from school extends into their lives, causing

them to develop self-esteem problems.

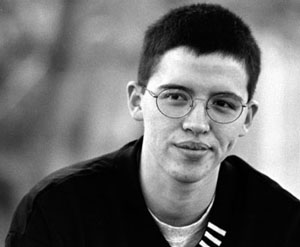

Nineteen-year-old Jeremy MacDonald, an enrolled Chippewa Cree

from Rocky Boy, says he learned American history in high school,

but didn't have an opportunity to take a Native American history

class until he became a student at the University of Montana.

"We should be learning about how we lost our land, instead

of how the other people got it," MacDonald says. "If

mainstream society were more educated (about Indian history),

they would understand us more."

Now that he's in college, MacDonald is learning as much about

Native American history and politics as he can, so that through

education he can help preserve "the old ways" as a

teacher, a coach and a role model to Native American children.

"Indians are fighting to hold on," he says. "We're

trying to get back our pride."

Gilham and her daughters continue struggling to maintain their

pride in the face of racism on a daily basis. They avoid certain

stores and restaurants where they know they'll be mistreated,

and they know by word-of-mouth the places where they will be

welcome, or will at least be allowed to cash a check.

Gilham says they're "getting used to it."

"We just want to walk through life like everybody else," she says. "You have to try not to wear (discrimination) like a cloak."

|

|

|

| Since Cheryl Smoker moved with her mother and children to Missoula, she says the sacrifice is exposing her kids to urban life "without the comfort of family." The mantel in their small apartment tells stories of their lives and the uniqueness of their culture. |

|

| Since urban life has brought racism into the daily lives of Glenda Gilham and her two youngest children, they tend to spend a lot of time at home. Lately, outside of her classes at The University of Montana, Gilham has spent most of her time doing detailed beadwork. |

|

| Kree Smoker, 7, shows off the sash and crown she won for being the best traditional pow-wow dancer in her age group. |

|

| Beaded jewelry is a part of the traditional pow-wow dance costume. Kylee Smoker, 14, shows her more modern approach to the ceremonial garb with a Nike swoosh and Chicago Bulls mascot. |

|

| "We should be learning about how we lost our land, instead of how the other people got it," says Jeremy MacDonald. |