|

Choosing Who Belongs

On Fort Belknap, tribal

enrollment matters

Story by Kim Skornogoski

Photos by Kim Eiselein

Running

Fish was the last of the great Gros Ventre chiefs. He died in

1906 with five rusting bullets in his body from his years as

a warrior fighting whites and warring tribes. After an epidemic

ravaged the tribe, Chief Running Fish adopted 100 Assiniboine

women into the band, marrying one, to strengthen the bloodlines

and to ensure their survival.

Almost 90 years later, Running Fish's descendants would regret his decision.

Willy Hughes has blue eyes. The navy blue baseball cap he

wears low on his forehead covers caramel-colored hair. He is

a fifth-generation descendent of Chief Running Fish and the son

of a Scot. When he was 2 years old his father left him and his

brother to be raised by his Gros Ventre mother on the Fort Belknap

Reservation in northcentral Montana.

Since then he's spent 20 years listening to his grandfather's

stories of Chief Running Fish and riding horses on his grandfather's

land. But despite his lineage and how he was raised, the people

of the Gros Ventre tribe don't consider him an Indian. Nor does

the federal government.

Neither does he.

"I'm a white man," he says, but the words come bitterly

because he's too white to be Indian and too Indian to be white,

and on the reservation it makes a difference.

It takes one-quarter Assiniboine or Gros Ventre or a combination

of the two bloodlines to be enrolled on the Fort Belknap Reservation,

which was established in 1888. With that blood quantum comes

the right to government money for health care and an annual "Christmas

cash" allotment of about $40. Enrollment also allows tribal

members to apply for federal college grants and gives them preference

when applying for jobs on the reservation and eligibility for

one of the homes built on the reservation by the Department of

Housing and Urban Development.

Hughes is 1/64 blood degree away from membership in the Gros

Ventre tribe. Because of that fraction, he can't work at the

reservation's volunteer fire department.

His Gros Ventre blood quantum began to wane when Chief Running

Fish married an Assiniboine woman and hasn't stopped diminishing

since. Hughes' ancestor's attempt to make the tribe strong is

now a factor in what is weakening tribal bloodlines, reducing

the numbers of people who are considered Indian. Now the tribes

permit a combination of the two tribal bloodlines for enrollment

eligibility, but for 25 years the bloodlines were separated.

Since 1921, the tribes have altered the enrollment requirements

four times, each change allowing more and more people to be enrolled.

Hughes works on his grandfather's ranch and lives in his mother's

home on the ranch. Through his mother, he can get health care

coverage at the hospital. But his grandfather Jay Mount, 80,

says Hughes doesn't get the same quality of care because he's

not eligible for the comprehensive coverage negotiated by the

tribe.

When Mount was 3, white men wearing crisp navy suits and suede

hats came to the reservation. Tribal members lined up side by

side so that the government could determine who should be enrolled,

entitling them to land and money. He remembers the men used an

interpreter to ask questions in Gros Ventre; his answers were

in English.

"State your name."

"Where were you born?"

"What is your father's name?"

"Where is your mother?"

Documents still at the reservation enumerate other queries.

"Did you ever leave the reservation to live?"

"Did you ever try to get enrolled in another reservation?"

"Did you ever receive land outside the reservation?"

"How many times have you been married?"

"What are the names of your children?"

"Where did you attend school?"

Two witnesses signed their names at the bottom of the paper

filled with his answers, attesting that Mount was telling the

truth. He, his parents and brother, were among the first Gros

Ventres to be enrolled at the reservation in 1921 -- the year

the tribes finally agreed to a land allotment. Mount's allotment

number is 133.

The original

allotment list has 1,189 names, and the questions and answers

of those Assiniboine and Gros Ventre people. Marlis Lone Bear,

an enrollment clerk for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, uses that

list to verify new people who are trying to enroll.

Today 5,266 are enrolled but approximately half of them live

off the reservation.

To enroll, an applicant fills out two pages of paperwork answering

questions similar to those asked in 1921.

"Where born?"

"What is your degree of Assiniboine/Gros Ventre Indian

blood of Fort Belknap?"

"What is your degree of other Indian blood and Tribes?"

"Is your mother enrolled at Fort Belknap?"

"What is her blood degree?"

"Is your father enrolled in another tribe?"

A certified copy of the applicant's birth certificate must

be submitted showing the parents' names. If the father's name

isn't on the birth certificate, the applicant must count only

the mother's blood degree. A man who later claims paternity must

prove it through a DNA test. If either parent is enrolled in

another tribe, the child must submit proof that he isn't enrolled

in that other Indian tribe.

Lone Bear then determines the applicant's blood degree, looking

through pages filled line after line with 701 possible fractions

of Assiniboine and Gros Ventre blood. If the applicant has enough

Indian blood to be enrolled, Lone Bear submits the name to the

Tribal Council. Once a month the council approves or rejects

the names, and a list is then distributed to grocery stores,

gas stations and the hospital, allowing enrolled members 30 days

to object to the potential tribal member.

Bertha Snow, 79, knows why it's so difficult to enroll.

She recalls what she says was the jealousy and greed that

came with a $211.19 government check in 1936.

"Before the treaty payment came up, any kind of Indian

blood meant you were Indian," she says. "That was before

people got greedy and you had to enroll under one tribe."

The Gros Ventre tribe received its first large treaty payment

in 1936 after it negotiated land rights with the federal government.

The Assiniboine tribe got no payment. But because the bloodlines

were by then so intertwined, Indians could choose at that point

to be enrolled in either tribe.

"The Assiniboine are the ones that labeled us $200 Gros

Ventres," Snow says. "It was derogatory. But money

was scarce at the time; Gros Ventres were going to get some money,

so they said, 'I'll be a Gros Ventre.'"

Snow's father signed her check over to the nuns to pay for

her schooling in Hays.

Even among families, Snow says, blood quantum was an issue.

Fred Gone, Snow's father, was a full-blood. Her mother was seven-eighths

Gros Ventre, a fact that Snow says he refused to let her mother

forget. Her mother's name was Mary John, a shortened version

of Snow's grandfather's name, Gros Ventre Johnny. It was a name

given to him by white men and Gone ridiculed his wife for it.

"It was a pride thing," she says. "He had to

prove to my mother that he was a full-blood and she wasn't."

Years later Snow's family would again be taunted for a fractioned

blood degree; this time the target was her granddaughter Michele.

Michele Lewis has lived on the Fort Belknap Reservation all but

five of her 37 years. She was raised by her grandmother in a

house where family photographs hang on pale blue walls next to

paintings of Jesus.

Lewis considers herself Gros Ventre in every way.

Every way, that is, except on paper. But somehow that fact

always manages to creep back into her life.

As a young girl, Lewis remembers what happened after she first

moved to the reservation from California. She was playing with

friends when a few old women came up to her and asked her who

she was. She told them. And she remembers vividly what they said:

"Oh, you're that little half-breed; you came from down

south."

"At the time it didn't mean much," Lewis says. "I

never really paid attention. But later on when I was in my early

teens I knew what they were talking about. I realized there are

distinct classes of people here and they all keep track of what

family you come from and how Indian you are."

In 1978,

Bertha Snow was thinking ahead and enrolled her granddaughter

in the Navajo tribe in New Mexico, enabling Lewis to apply for

money for higher education. Lewis is half Navajo and 1/164 away

from qualifying for Gros Ventre enrollment.

Unfortunately, in 1980, when it came time for college, the

Navajo told Lewis they didn't have enough school grants for tribal

members who lived on the reservation, let alone for her. She

also didn't qualify for money from the Fort Belknap Reservation

because enrollment is required to qualify for the college grants.

Lewis worked her way through school for three years, winning

a few college scholarships, but had to drop out when college

costs grew too high.

She went to work in the Fort Belknap Community College registrar's

office, where she filled in for her boss while the college looked

for his replacement. Lewis applied for, but didn't get, the permanent

position, she says, because she was not enrolled, even though

the job was one of few on the reservation that didn't give hiring

priority to tribal members. Fortunately, she says, the enrolled

candidate declined the job and she was second on their list.

"Whenever I apply for something I'm very careful to do

a good job and I check to make sure I can qualify," she

says. "It gets frustrating to try to do something and keep

hearing no. The disappointment is the worst."

Lewis looks down at the papers on her desk. Her long black

hair cascades down her back, trickling over her slumped shoulders.

"You get used to it," she says with resignation.

But still, it makes her weary.

"It's just like not being an Indian even though you really are," she says.

Nedra Horn's house isn't much. It also isn't hers.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development gave Fort

Belknap money to build houses on the reservation and the authority

to choose who gets those homes.

Horn is a Little Shell, a band that doesn't have a reservation.

And that means she has nowhere to enroll.

Because she married an Assiniboine, the Fort Belknap tribal

government gave the couple a home in Hays. But when they divorced

recently, the home went to her husband even though Horn was living

there with her three children and paying for the home. Her ex-husband

wanted to give Horn the house but couldn't because she was not

enrolled. Instead, he gave it to her oldest daughter, Brandy,

who is 20.

Brandy is an enrolled Assiniboine, using her father's bloodline.

She is half Assiniboine, but because the Assiniboine tribe divided

into two reservations - Fort Belknap and Fort Peck bands - her

blood degree is also split. She has slightly more than a quarter

Fort Peck Assiniboine, and slightly less than a quarter Fort

Belknap Assiniboine. But while the Fort Peck Reservation combines

the two bloodlines to come up with an individual's blood quantum,

Fort Belknap does not.

In 1972, a settlement payment was made to anyone who was one-eighth

Gros Ventre or Assiniboine, a definition that would continue

for the next 11 years to determine who could be enrolled.

Brandy was lucky; she was born before 1983 when the Distribution

Act was passed, giving another treaty payment to the tribes and

changing the definition of an enrolled member to a quarter tribal

blood. Her younger sister, Lacy, and brother, Scotty, were born

after the change, which means they are a fraction away from enrollment

at Fort Belknap, despite their half Assiniboine blood.

To enroll instead at Fort Peck, Lacy, 14, and Scotty, 5, would

need to have their father also enroll there and relinquish his

tribal membership at Fort Belknap. That would mean he couldn't

get a job where he lives.

"A lot of people don't know that my youngest children

aren't enrolled," Nedra Horn says. "People see my young

dark Indian daughter and think she's enrolled."

But Horn is hopeful things will change.

"The blood quantum is thinning out," she says. "Pretty

soon my kids' blood quantum may be acceptable."

Lacy's cheekbones boldly mark her ancestry. She looks like

her father and she's proud of it. Her skin is dark, her eyes

exotic, her hair flows black.

Scotty seems attached to his mother's hip. A constant smile

fills his round face. When his mother carries him, his pale brown

cheek melds with hers.

This year, the school had money from the government to buy

shoes for the enrolled children at Hays/Lodgepole School. Horn,

who teaches second and third graders there, saw the forms and

whispered to a teacher "but they're not enrolled."

The teacher told her to fill them out anyway and see what happened.

Her Assiniboine-looking daughter was given the $30 for shoes,

while her "half-breed" son was not.

"I'm a half-breed," Horn says. "This community

is so small that everyone knows that. It's hard. We're really,

really looked down on. But as long as you don't get too involved

in things people respect you."

Brandy may be enrolled, but because of her light skin and

the "half-breed" stigma of some family members, she

says she is often hit with the prejudice that comes from not

being enrolled. Horn says Brandy has applied for temporary secretarial

jobs and was fired within hours because people have asked why

she got the job when another enrolled member needed one. Brandy's

grandfather, Gilbert Horn, is a longtime Assiniboine leader who

has tried to open doors for his grandchildren. He has also fought

battles for his tribe.

Horn, 85, has been on the Assiniboine treaty committee for

the past 28 years, taking over a role his father had. The treaty

committee negotiates with the federal government, representing

Fort Belknap tribal members' interests in reservation lands.

In the 1950s, Horn was the voice of the Assiniboine tribe.

Most of the elders couldn't speak English and Horn was there

to represent them in the white man's world using the white man's

ways.

"I was younger then," he says. "It didn't bother

me to cut my braids and talk English."

Horn traveled to Washington, D.C., several times a month representing

the tribe on different committees, lobbying Congress on Indian

issues.

He remembers one trip in particular. He walked into a room

at the Watergate Hotel and was greeted by 17 white lawyers. He

sat at the end of a long, gleaming oak table and the lawyers

in their suits sat along the sides. It was there before all those

white men, that Horn decided new enrollment guidelines for the

Fort Belknap tribe.

Jay Mount and Bertha Snow also sat on a treaty committee, both

for the Gros Ventre tribe. They remember the discussions about

who could get treaty payments and who would be in the tribe.

Now they express regret at how things turned out.

"I think it's wrong," Snow says. "It's wrong

for the younger generation to scratch and scrape for information

to prove who they are to the white man when they look like Chief

Joseph."

But any change must start with the tribal council, elected by

people who already are enrolled.

William "Snuffy" Main has been on the tribal council

11 of the past 15 years and the other four years he spent working

for the BIA in Washington. He says a change isn't likely.

"There's been a lot of discussion about it," he

says. "My position on it is blood degree may not be the

ideal way to go about it, but show me another way. How do you

look in somebody's heart and determine whether they are Indian

or not?"

Expanding enrollment would mean that money, land and other

benefits would be further divided. And that, says Main, is not

something the people who now get the benefits would favor.

Joe Fox, who is a tribal councilman and chairman of the enrollment

committee, has grandchildren who don't qualify for enrollment.

He knows that they probably never will.

"You can't change things now; there's just too many factors

that get tangled up in it," he says. "There's been

talk about it, but I don't see anything happening."

The tribal

council has taken steps to incorporate the people who live on

the reservation and can't be enrolled. They've created "community

members," unenrolled people who have a parent who is enrolled.

But community members don't get any of the benefits that come

with being a member of the tribe, including the honor.

"It's just a title," Michele Lewis says. "It

doesn't mean anything when you look for a job or when people

see you on the street."

The community member title may be the best Lewis will ever

get.

Non-Indians see her as Indian and judge her because of it. Members

of her tribe see her as a half-breed and some show her contempt.

Luckily, she says, there are others who don't see it that

way and will fight for her and others like her. Jay Mount is

one of them.

"As long as you have one drop of Indian blood in you," Mount says, "you're still a damn Indian."

|

|

|

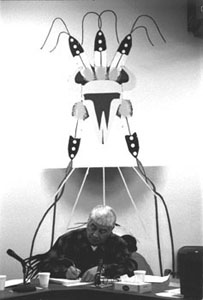

| Joe Fox, a tribal councilman and chairman of the Fort Belknap enrollment committee, awaits the beginning of a council meeting. Fox has grandchildren who don't qualify to be enrolled and does not foresee any changes in enrollment regulations. |

|

| Jay Mount asks his grandson Willie Hughes some questions before Hughes leaves to move cattle for the day. Hughes is 1/64 blood degree away from eligibility for enrollment in the Gros Ventre Tribe. His mother is Gros Ventre and his father is a white man. |

|

| Every month a list of people approved for membership in the tribe is posted at places across the reservation. Tribal members have 30 days to object to the enrollment of a potential member. |

|

| Marlis Lone Bear, enrollment clerk for the BIA, looks at a list of the questions asked when the first allotment rolls were made. Several other books have family trees drawn out and all tribal members' blood quantums recorded in them. |

|

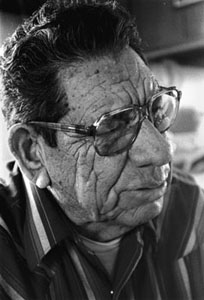

| Serving more than 25 years on a treaty committee, Gilbert Horn, an Assiniboine, uses his knowledge of Fort Belknap issues to lobby not only for his tribe, but for his family. |