|

An Uneasy Education

Going away to college

-- and returning

to the reservation -- isn't always easy

Story by Thomas Mullen

Photos by Karl Vester

Iris Heavy

Runner got an education at the University of Kansas. But it wasn't

what she expected.

All her life Heavy Runner had been around Indian people. A

Blackfeet with a disarming smile and cascade of shiny black hair,

Heavy Runner was raised in Browning and spent two years at a

Native American junior college. But when she got to Lawrence,

Kan., she found herself in an alien environment. She didn't understand

the way students and professors thought. And especially how they

spoke.

Nobody in Browning used two-dollar words or scientific-sounding

terms. Everybody in Lawrence seemed to. And, she says, everyone

but her seemed to understand. Gradually, though, Heavy Runner

found her way.

"My language started changing," Heavy Runner recalls,

eyes beaming behind round glasses that frame her round face.

"I started understanding more English and I could write

it."

But that new way raised questions for her about her old ways.

"I had learned how it worked and I started wondering,

'Should I be doing this?'" she says.

She wanted to return after graduation to the 1.5 million-acre

Blackfeet Reservation that lies along the eastern slope of the

Rocky Mountains in northcentral Montana. She worried how she

should speak back home. Would her friends say she was trying

to act as if she were better than they were? Would they say she

was talking like a white girl?

Heavy Runner knows these same questions are being asked by

hundreds of other Indian college students; she deals with those

students regularly.

As an adjunct professor in UM's Native American Studies program,

she routinely helps Indian students cope not only with academic

rigors, but often with what she calls a college-induced identity

crisis.

For Indian students attending college, maintaining their identities

in a culturally diverse setting can be education's biggest challenge.

Those who learn to live in two worlds represent perhaps their

tribe's best assets in their reservations' struggle for improvement

and economic growth.

But Native Americans who have proven themselves in university

classrooms often come home to find they must prove themselves

to their own people. A four-year stay in college can culminate

in American Indian graduates returning home to people who no

longer relate to them.

Heavy Runner remembers the frustration.

"Here's the dilemma." she says. "My family,

my grandmother, told me all my life, 'Get an education, but don't

change.'

"Impossible!" she says, leaning forward in her chair

as her eyes show her exasperation.

Change

has been the definition of Billie Jo Kipp's college career.

Four years ago, Kipp was 36 and just a year removed from drug

and alcohol rehabilitation. Stuck in a dead-end job in her hometown

of Browning, Kipp decided she wanted more, and moved to Great

Falls to pursue her education.

While her husband remained in Browning to run a business and

her oldest son stayed to play basketball, Kipp attended the University

of Great Falls, living with her three younger children in family

housing there.

"We lived very poor," Kipp recalls. "It was

the hardest time of my life."

Despite this, she graduated with a bachelor's degree in counseling

psychology, and now at age 40 is a Ph.D. candidate in psychology

at the University of Montana.

Kipp's undergraduate experience gave her a new-found confidence,

but was also the breeding ground for one of her biggest fears

- the fear of losing who she is.

"You change too much and you lose your connection with

home," Kipp says."My goal is to come back home, [but]

to come back and not know what's going on and not be connected

is really scary for me."

Kipp's family has joined her in Missoula, where her husband

is a senior in Native American Studies. That renewed closeness

is a comfort but she relies on frequent trips to see her mother

in Browning for a connection to her roots. Even there, however,

Kipp is reminded of the differences between herself and many

on the reservation.

"When I'm at the university, I have to speak with a certain

terminology and do things the way I'm being taught to do them,"

Kipp says. "When I come home and talk to my mom, she tells

me, "Don't use those words here. Don't talk like that here."

She knows it's an attitude she will have to deal with when

she returns home to work.

So does

Marsha Last Star.

She worked at the tribal court in Browning for 13 years before

earning a degree in social work from UM. Now a first-year law

student in Missoula, Last Star says many former coworkers see

her education as a threat more than a benefit.

"We could make some big changes here if people would

look at educated people and say, 'Where could they help? Let's

use this knowledge.' But it doesn't happen that way," Last

Star says.

Both Kipp and Last Star agree that it's easy to understand the

indifference to their education. Throughout their years in the

classroom, they have become outsiders.

"You've been gone and you don't know what it's like any

more," Kipp says. "You've been disconnected, and the

people here have been through everything year after year, and

they have a right to what they have here."

A college education remains a relative rarity for Indian people.

The last census shows that while more than 75 percent of non-Indians

in Montana have at least a high school diploma, only 3 percent

of Indians do. And the dropout rate at Browning High School in

the 1995-96 school year was 16.6 percent -- almost three times

the state average.

For those college students who return to the reservation to

work, success can be a touchy combination of patience and tact.

Back in Browning over spring break, Kipp says she's begun to

accept that her reintegration into the Blackfeet tribe may be

as demanding a process as getting her education was.

"Eventually I can come back and begin to meld again with

the people here and become a part of the community," Kipp

says. "But I've got to earn that. It's not like I can come

back with all these ideas and say, 'Okay, you guys gotta do this.'

I'll be put in my place very quickly."

That's if she can find a job at all. Unemployment in Glacier

County, which has a population of close to 60 percent Blackfeet,

was 16 percent in March. The state Labor Department reports that's

the highest jobless rate of any county in Montana, where the

statewide average is about 5 percent. The real rate on the Blackfeet

is probably much higher, as it is on the state's other reservations.

This rate counts only those who are actively seeking work.

When jobs are available, the overwhelming source of employment

opportunities for college graduates are government jobs in health

services, social work, education or tribal government.

But a

lack of jobs isn't the only obstacle facing returning college

graduates in Browning, says Blackfeet Tribal Judge Howard Doore.

While he prizes and encourages education, he says the plain fact

remains that many college students are still distrusted on the

reservation.

"It all depends on how they act," says Doore, whose

daughter Adra attends the University of Idaho. "Some speak

from the mouth and not the heart, and some have a chip on their

shoulder from

college."

Conrad LaFromboise, director of the Blackfeet Higher Education

Program, says college graduates who return to the reservation

are up against a mentality that often shuns change -- and those

who bring it. The result, he says, is that Indian students are

often at a disadvantage when coming home for a job.

LaFromboise says reservation residents accept the idea that

education is important and a college degree is desirable.

"But you've still got a lot of people who look after

their own here and if they need a job, they get it -- even if

they may not have the skills," he says.

He says hiring on reservations is not unlike the political

"crony" system common in early-day politics. While

the western world today frowns on such hiring practices, he says

it's all part of the Indian code.

"A long time ago, when Indian people traveled in bands,

leaders of those bands looked out for those in their group,"

LaFromboise says. "You've still got a lot of that sentiment

around."

Jolene

Weatherwax probably wasn't hurt by this sentiment. After graduating

from Browning High School, she rose to become the director of

ambulance services for a Browning medical service with only a

high school education -- a climb not uncommon in reservation

life. She says it wasn't hard.

"They'd just put a job in front of me and I'd get it

done," she says.

She says when people return to the reservation waving master's

degrees and calling for change, they threaten to disrupt the

way things work on the reservation.

Now 42, Weatherwax is in her second year at Montana State

University in Bozeman, where she majors in psychology. She says

she knows she has a fine line to walk if she returns to the reservation

to work.

"If you go home and point at your degree and say, 'This

piece of paper says you have to listen to me,' nobody's going

to listen to you," Weatherwax says.

Melvina Malatare, 49, has worked in Browning since she finished

school at UM in 1989. She has been the director of the Pikuni

Family Healing Clinic there since November, and remembers the

trials of returning to work on the reservation.

"When I first started working there weren't too many

people there who had degrees or as much education as I did and

sometimes I tried to hide it," Malatare says. "I didn't

have to change the way I talked or anything but I just wanted

to be one of the group and I didn't feel I needed to flaunt (my

education)."

Her success, she says, has been a product of a positive attitude

that has seen her through a divorce, a burned home and the loss

of her son in 1996 in an alcohol-related car crash. That quality,

she says, is coupled with a willingness to compromise -- both

attributes she claims to have acquired in college. Though a still

unwritten paper keeps her from her degree in social work, Malatare

says she is a different person because of her years at UM.

"I know who I am and I didn't before (college),"

she says. "I have beliefs and values and I stick to them,

but I am also subject to change my beliefs and am not rigid in

having my way or no way."

Despite the difficulties, getting an education is key for

today's Indians, says Wayne Juneau, the director of an alcohol

and drug treatment center in Heart Butte on the reservation.

Juneau remembers how as a 24-year-old graduate of the University

of California at Berkeley, he went to Washington, D.C., to work

as a lobbyist for Indian affairs where he met a fellow Blackfeet

woman who taught him the ins and outs of the city's political

machinery.

The insight came with strict instructions that he pick someone

from his tribe and teach them what he knows.

"That's the way it is in the tribe: those who know help,"

Juneau says.

He says tuition fee waivers for qualified Indians and tribal

community colleges on each of the seven Montana reservations

have given Native American students increased access to education.

He says it is an institution Indian people can no longer afford

to view coolly.

"In order for us as Indian people to become equal in

every aspect of life we need an education," he says.

Perhaps fittingly, Iris Heavy Runner has a more traditional

answer. Education is like a blizzard, she says.

"We have to pay attention to what our ancestors told

us about the buffalo," Heavy Runner says. "The buffalo

never run away from a blizzard because they know if they did

it would follow them and the chances are they wouldn't make it.

"So, as students, we have to be like those buffalo. We have to put our head down and go right for that blizzard."

|

|

|

| Jim Kipp is majoring in Native American Studies at The University of Montana, nearly 20 years after his first attempt at college failed. His wife, Billie Jo, is a Ph.D. candidate in psychology. |

|

| Robert Juneau, 22, was raised in Browning and is now studying history and political science at The University of Montana. His Uncle, Wayne, graduated from the University of California-Berkeley and encourages Bob to finish his degree. "In order for us as Indian people to become equal in every aspect of life, we need an education," Wayne says. |

|

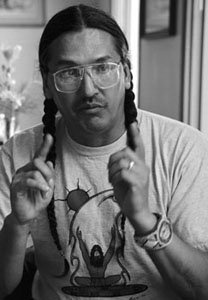

| "Here's the dilemma," says Iris Heavy Runner. "My family, my grandmother, told me all my life, 'Get an education, but don't change.'" |

|

| "I think people (on the reservation) are intimidated by educated people who come back and try to get a job," Marsha Last Star says. |

|

| With a little help from her husband, Jim, Billie Jo Kipp works on her psychology thesis at her home in Missoula. A graduate student, Kipp is farther down the educational path than her husband, but yields to him when tradition is involved. "On the reservation, I put my husband first because that's the way it is. When he's in ceremony, he's first," Kipp says. "But (at school) I'm pretty much first because I'm ahead of him in my process." |