|

Owning Indian Country

Dividing trust land among

heirs

can be like trying to split a hair

Story by Lisa A. Kerscher

Photos by Melissa Hart

Gladys

Jefferson and her family spent more than $1,500 fencing 120 acres

that were not even hers.

The land had been in her family since the turn of the century

when the federal government allotted Crow Reservation lands to

individual tribal members. The plan was to turn the Indians into

farmers and assimilate them into white society. Many Crows, like

Gladys Jefferson's parents, were given few clues and little incentive

to find their land on the 2.3 million-acre reservation.

Twenty years ago, Jefferson decided to find the family's holdings

and put the land to use.

"My folks had never known where their lands were,"

Jefferson says. "We figured we'd go find it so we could

fence it off and take cattle there to graze during the summer

if we couldn't get a better lease on it."

Fortified with a township and range location from her land title, Jefferson headed to the reservation's Bureau of Indian Affairs land office. Referring to a map, the BIA agent showed Jefferson about where the land was located up a gravel road near old Highway 87.

"He told us to go on the road so far, and what landmarks

to look for, and that's where it would be," she recalls.

Kneeling on her wood floor at her home in Crow Agency, Jefferson

pores over an unfurled map that plots land ownership on the Crow.

Her finger retraces her quest along the reservation's myriad

property lines, past the jumbled hues that signify ownership.

The family drove west from Crow Agency for awhile. Turned

up the gravel road. Passed a distinct group of trees. Found the

spot and began to build the fence. "Whenever someone had

some money, we'd buy more supplies and work on it," Jefferson

says.

But when a BIA land appraiser finally went out to assess her investment, he found out her land was farther north, outside the fence.

"It was clear on the other side of what he first told

us," she says. "The kids kinda got disappointed. Three

months of work and we ended up taking down the fence."

That mistake

- and a host of other problems - results from the modern mess

of land ownership on the Crow Reservation.

Darryl LaCounte, land titles and records manager for the Bureau

of Indian Affairs in Billings, says such problems are the result

of "a lot of laws that were passed to protect Indians that

are now really binding."

Facing a wall of maps in his corner office, LaCounte refers

to a land title that shows some of the complications those laws

cause. When a landowner dies without a will - a common occurrence

on the reservation - the law splits the property evenly among

any children, if no spouse survives.

But inheriting land on the reservation isn't merely a matter

of splitting up the acreage into smaller pieces. If an owner

holds one-seventh of an interest, for example, he owns one-seventh

of every square inch of the parcel. That means owners ultimately

end up with scattered fragments, making them difficult to put

into productive use.

"A lot of times you feel so bad for these people - they

think they own so much, but they own only this," LaCounte

says, indicating just a fraction.

Some of the original allotments to Crow tribal members were

spread out across the reservation. That means land split into

fragments by the federal trust inheritance laws is further fragmented

by the nature of the original land grants.

To make matters worse, sometimes land falls out of trust status

- and becomes fee land - and the BIA no longer has jurisdiction

over it. This can happen when land is sold to non-Indians or

because a non-Indian spouse inherited a fractional share. If

an owner of trust land dies without a spouse, children or a will,

then the share returns to the tribe.

"It's a difficult thing to manage, because most people

are not aware of what happens to their land when they die,"

LaCounte says.

These conditions make using the land a battle against red tape

and hard feelings.

LaCounte says co-owners have the responsibility to either

assert their property rights or be compensated for someone else

using the land. But the land fractionation is so bad that "many,

many people make less than $1 per year," he says. "There

are people who own so little that their interest never generates

a penny. Never."

On one 160-acre tract, for example, several people own 1/332,640

undivided interest. If consolidated, each of those owners would

be sitting on a piece of land the size of a couch. Only after

several thousand years would a penny be tallied from it, assuming

the fractionation stopped there because they had no heirs.

In the

early 1980s, Congress passed laws that allowed tribes to take

land from individual owners whose share was less than 2 percent

if the income from the land didn't total $100 during one of the

five years before the owner's death. William Youpee had a will

and his heirs, not the tribes, should have acquired his small

holdings in Montana and the Dakotas. But Youpee had never been

notified that those shares might be taken when he died, so his

heirs challenged the law. About a year ago, the Supreme Court

ruled it unconstitutional, because the owners were not compensated.

Compensation can be very costly, though. Youpee, for example,

owned undivided interests in several tracts of land across three

reservations. Their value totaled $1,239. The appraisal work

done to compensate the heirs cost more than the land was worth.

"We're just in this fix," LaCounte concludes, "and

everything you do probably costs more than your interest in it."

A dozen years ago, Charles Yarlott had land that was not in

fractions and he wanted to put a house on it. However, his 460

acres were mostly inaccessible by roads, so he proposed trading

it to the tribe for 400 acres up Reno Creek, close to Crow Agency.

The trade took three years, but his sole ownership is secure.

Yarlott got a brand new modular home, complete with furniture,

through Housing and Urban Development a couple years ago. He

planted it just off the gravel county road, realizing that he

needed to get electric lines strung out to his place. Yet three

years later, the power lines still end two miles short of his

lifeless house. Meanwhile, he's powering up for court.

The Rural Electrification Administration estimated the total

cost to extend the lines at nearly $15,000. Earlier this year,

the tribe agreed to cover 75 percent of it, and REA trimmed the

cost some. But Yarlott is still left with a $3,200 bill. "They

need the whole sum up front," Yarlott says, "but I'm

not Howard Hughes. I'm just trying to make a living. I offered

to pay $50 a month with the regular bill, but they wouldn't budge

whatsoever."

Ironically, REA still owes Yarlott for building lines across

his father's allotment - the 460 acres he traded - in the early

1950s. Yarlott's offer to simply swap tabs was refused. When

he recently got $3,000 from the federal housing department to

help cover the new wiring job, he thought he was in the clear.

But REA "didn't want it," he says. "They told

me to send the check back." Yarlott says the power co-op

insists on resolving the old easement dispute, before moving

ahead with the new lines. It's still in dispute.

So for now, instead of living 10 miles closer to his job at Crow Agency, Yarlott still lives in St. Xavier, one of the five towns in which most Indian families live on the reservation. His century-old home, on a dirt road just off the highway, used to belong to his in-laws. The Yarlotts pay taxes on it, because the town owns the land. Yarlott's place is one of several homes lined up opposite a rusting rural fire truck and an empty foundation left from a burned-down house. A silent schoolyard is a stone's throw away.

At the highway's edge, the abandoned grade school's warm brick

face and broken windows are engulfed in horseflies buzzing louder

than the passing traffic. A green chalkboard inside announces

a meeting scheduled for Oct. 18, 1983.

Yarlott's decade-old dream of tranquil security has disintegrated.

After he tows REA into court, Yarlott says, the BIA is next.

"For faulting on their trust responsibility," he says. The BIA and the tribe's superintendent, Yarlott contends, are supposed "to see that Indians get a better deal. But the BIA said they blamed it on us for letting it happen."

Yarlott is determined to get justice on the reservation, but

an attorney will cost money, which is hard to come by because

apparently banks rarely loan to Indians.

In a recent

report from the General Accounting Office, the investigatory

arm of Congress, out of the 1.2 million Indians living on trust

lands nationwide, only 91 got conventional mortgage loans for

homes between 1992 and 1996 and 128 got federally guaranteed

private loans between 1983 and 1997.

Gerald Sherman, an Oglala Indian, has worked as a banker for

10 years. "In banking, I can't say racism doesn't exist,"

he says, but he believes many people's sense of discrimination

is rooted in misunderstanding and the absence of business standards.

Most Indians are unfamiliar with how banks work, because few

exist on reservations. Sherman works at Hardin's First Interstate

Bank, just outside the Crow Reservation. He says lenders often

won't risk doing business there, because reservations lack Uniform

Commercial Codes, which "spell out all the rules for doing

commerce." On the reservation there are no codes dealing

with foreclosure and repossession issues, for example.

Sherman says most banks near reservations are lending anyway,

and updated federal regulations makes sure banks serve local

low-income residents without bias.

More often, discrimination may be a matter of perception.

"If a white person gets treated badly by a bank, he sees

it as bad customer service," Sherman says. A person with

color may see it as racism. The bottom line is that "people

are more comfortable dealing with people like themselves."

Unlike Yarlott, most landowners have given up any dreams of

living on their land. Ninety-nine percent of trust land on the

Crow is leased, most often to non-Indians.

Lynda Whiteman owns 1/35th of 480 acres - about 14 acres if

it could be consolidated. She used to get about $90 a year by

leasing it with the other owners to a non-Indian farmer, Marvin

R. Knutson, who has lived and farmed near Reno Creek for 27 years.

Thanks to her husband's severance pay and his understanding of

the leasing game, her annual profit has been $1,500 to $3,000

over the last three years.

"The bottom line is money," her husband,

Everett Whiteman, says. You need money to make money."

When he left the BIA leasing department after 29 years of service,

Whiteman used his severance pay to help his wife outbid Knutson's

lease. The Whitemans pay the annual leasing fee of $5,600 and

hire Knudson to farm it, but they and the other owners still

make more from it than before.

Even if an Indian wanted to farm the land himself, a used Ford tractor might cost $2,000. Owners wanting to invest in their land face other obstacles as well. The Whitemans, for example, had 3,000 bushels of wheat in storage they wanted to use as collateral for a loan until they sold it at higher market prices. Knutson co-signed for them a year ago at the First Interstate Bank in Hardin to confirm their wheat stock.

"I don't have a problem with helping these people,"

Knutson says. "If I know you, and I know your word is good,

then to hell with the bank."

Knutson tends about 3,000 acres - farming wheat and hay and

running cattle. Some of it he purchased as fee land, but he estimates

that he leases a lot of it from about 250 owners. "I'm one

of the few dinosaurs left that do my own leasing work,"

he notes. Unlike most people who go through leasing companies,

"if you're going to lease somebody's land, I've always felt

it's common courtesy to meet one-on-one" with the landowners,

he says.

Sometimes, though, many people don't know they own land and many others have such a small interest, they don't care what happens to it.

"Most people won't put $10 in their gas tank to decide

on something they'll lose money on," Everett Whiteman says.

Thus, a lease can be signed with only 51 percent of the owners

agreeing to the contract. The superintendent can sign for the

minority, whether they want it or not. To allow one owner to

live on part of the land or to mortgage it, all of the owners

have to approve.

Conflicts between owners often cause emotional tension, as well. Whiteman says some of the strongest resentment comes "when someone owns a share through a second marriage, and nobody knows it until the lease comes up."

A second spouse will get one-third share and children from

the first marriage will split two-thirds of it. "That's

there on just about every tract," he says.

Even Lynda Whiteman has been fielding uncomfortable calls

from co-owners recently. Although she pays the annual leasing

fee on time and everyone's making more money than with the old

contract, some still aren't satisfied. Some of these owners prefer

to go through a leasing company. By doing it the old way, they

could get money from the leasing company before the yearly lease

payment's due, but they usually have to pay 15 percent interest

for the advance.

Many of

these land-use challenges arise because the owners don't understand

the complex laws. Over the last several decades, Everett Whiteman,

now a clerk for the tribe's Crow Land Resource Committee, has

had people come into his office saying, "Tell me where my

one-hundredth of an interest on that tract is."

Gladys Jefferson believes the Crow's tradition of trust has

reinforced an outdated way of doing things.

"We never questioned our elders," she says "so

we figured our parents knew what they were doing" in signing

the leasing contracts the white people encouraged. "Even

$100 was a lot to them. In the long run we found out we were

cheated."

But younger land owners, such as Jefferson's eldest daughter,

Jannell Jefferson, have begun questioning the customary compliance.

While growing up here, Jefferson, 24, watched a non-Indian farmer

go from driving a beat-up truck and living in a run-down house

to owning a new Ford, six other trucks, a car phone and a nicer

house. Her family got a yearly $25 check from leasing the land

to him.

What she saw as a blatant inequity fueled her defiance of

the old procedures, questioning everything out loud in a way

uncommon among Indians. The new attitude upset her mother, though,

especially on lease renewal days. "I would tell her, 'Don't

be so mean. They're good to us,'" Gladys Jefferson recalls.

"I was always worried about ruining those relationships."

Her daughter argued that the leasing people acted nice because

they wanted the cheap contracts signed quickly.

Gladys Jefferson understands her daughter's frustration, though

it does make her uncomfortable.

After signing the lease, "once you walk out that door,

you're an Indian," Gladys Jefferson says. "We don't

know if they've screwed us or not, but they're trying to make

money off us."

Today Jefferson and her family know where their lands are, and she hopes her children become more educated about the issues.

"Now it's tradition," Jefferson says. "Every

Mother's Day, we go way out in the boonies and check out our

land." They also take pains to "show our grandkids

how to read the (property) book."

Some people, like Darryl LaCounte and Everett Whiteman, try to encourage owners to think ahead and write a will outlining where the land should go.

"But many of these people are superstitious," Whiteman

says, "and they see it as writing their death sentence."

Some Indians think most of the conflicts over land would disappear if all the individual holdings reverted to tribal ownership.

Then "we wouldn't have all these jurisdictional problems," Everett Whiteman says.

The appraisal process to compensate everyone would be long

and costly, but the government would only have to do it once.

Some lawyers suggest several other solutions: promoting voluntary

consolidation; designating a single beneficiary; swapping interests;

and, most important, educating owners so they can assume a more

active role in what happens to their land.

All agree these deep-rooted problems need to be resolved. But most familiar with the land ownership situation acknowledge that the problems are so complex that creating legislation to remedy them is difficult. Yet with the birth of every new heir, delaying a search for a resolution will only continue to divide the land and its people.

|

|

|

| The Crow joined Gen. George Custer in the battle of the Little Bighorn. The tribe was known for cooperating with the government and that may be the reason its members received the largest land allotments in Montana, says BIA land titles manager Darryl LaCounte. |

|

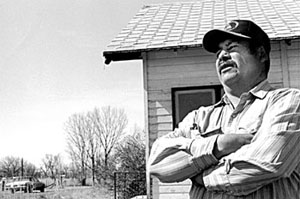

| Charles Yarlott and his family live in a century-old deteriorating home while he tries to find a way to get power lines to his new home up Reno Creek. |

|

| Gladys Jefferson says her generation never questioned what was happening to their land because they trusted the white man and were taught it was disrespectful to question elders. |

|

| Marvin Knutson farms fee land and trust land he leases from Crow Indians. "I've never had any problems with the BIA, but it's somewhat different and sometimes more difficult. It's easier to deal with the people than with the bureaucracy," he says. |

|

| A broken-down wall gives way to a mural in the St. Xavier School. |