|

Living with Dying

Losing a loved one is

difficult for anyone,

but for Indians, the pain is all too frequent

Story by Paige Parker

Photos by Ann Williamson

It was

Maynard who was crushed beneath the boulder.

Two other of Mae Whitedirt's children died in infancy, of

pneumonia. Another daughter drank poison and was hospitalized

five months before succumbing. But it's Maynard and his cousins

that everybody on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation still talk

about.

Maynard Whitedirt and four of his cousins were playing tag

in the sandrock, sage and pine-covered hills near Lame Deer,

on the reservation in southeast Montana two hours away from Billings.

As they played, rocks tumbled from above, claiming all but one

of the children. Maynard was 7. It was 1968. And it was the beginning

of hard times for the Whitedirt family.

Mae Whitedirt lost four of her seven children before her 46th

birthday. She's seen too much death. But her story is not unusual

in Native American families.

Indian Health Service statistics reveal what many Indian families

know from experience: Indians die young more often than non-Indians.

An Indian in the United States is twice as likely as a non-Indian

to die before the age of 65. The causes are many, but the result

is the same.

Four generations of the Whitedirt family have suffered the

human drama behind those statistics.

Whitedirt doesn't like to speak much about the four children

who didn't make it. As she sits in the kitchen of her tidy, battered

house, she directs attention instead to the pictures of her 15

grandchildren that cover the wall above the fireplace. She has

raised six of them.

Elrena Whitedirt is one of Mae Whitedirt's three surviving children. She gives details about the deaths of her brothers and sisters that her mother can't or won't tell. She says that Jacqueline and Farley were the babies who died, years apart, of pneumonia. She blames what were inadequate medical facilities on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation for their deaths.

"They both died on the way to the hospital in Crow,"

she says, referring to the adjacent Indian reservation.

Indian babies die at a rate 26 percent higher than non-Indian

babies, the Indian Health Service reports.

Elrena was 10 at the time of Maynard's accident. The children had all been playing near Elrena's grandparents' house when the game changed course. They ran off toward the red hills, which many Northern Cheyennes consider sacred. Elrena said the accident scene was a gruesome one.

"When we found them they were all smashed up," she

says. The rock that fell on them weighed close to 20 tons.

Indians have a 265 percent greater chance than non-Indians

of dying in accidents, the IHS reports.

The day after the accident, the Whitedirt family brought a

medicine man out to the red hills. As they stood at the spot

where the boulder fell they sang death songs and burned cedar.

What happened next, Elrena Whitedirt says, could best be described

as a vision of the previous day's tragedy. Whitedirt says the

family heard a dog barking, the voices of the children laughing,

the sounds of running, then rocks tumbling and then screams.

She says the sound of a dog barking continued long after the

sound of the children's screams fell silent.

Whitedirt says traditional Cheyennes whispered that the deaths

happened because the children had shown disrespect for the sacred

hills by running and playing there. The Whitedirt family conducted

their mourning in the old way, with a wake, a funeral, a feast

and a give-away.

"My grandparents had a house full of furniture, with

horses and cows and chickens," Whitedirt said. "When

they were done, it was empty. They gave away everything. We lived

in tents after that. Within a year's time, they had everything

they used to have."

The family continued to memorialize the fallen children with

an annual pow-wow celebration. The give-away was also held each

year, and each time the family was left with nothing but an empty

house.

Then the giving stopped and the drinking began.

"It wasn't the same," she says. "The family

broke apart. That's when alcohol took over." Whitedirt says

they have never really healed.

Whitedirt was an eighth grader in 1972 when her sister, Linda

Lou, died after drinking Drano.

"She came home drunk and went into the bathroom. When I went in there she was puking up black stuff. It was sudsy," Whitedirt says.

Though the incident took place New Year's Day, the Drano took

its time killing Linda Lou, who was 28. She spent five months

in a Billings hospital before dying in May. Both Whitedirt and

her older sister quit school and joined their parents in Billings,

working to help with the family's expenses.

Though the Whitedirt family doesn't call Linda Lou's death

a suicide, Indian suicide rates are 85 percent higher than those

of non-Indians. Indians are also three times more likely than

non-Indians to die from poisoning.

Now four

children are gone. And the tragedies go on, extending into another

generation.

Ledeana Little Sun, one of the grandchildren Mae Whitedirt

raised, is trying to learn how to be strong at 22. She was 18

years old and five months pregnant when she lost her arm leaping

onto a moving train. She had been drinking with her mother, her

uncle, her boyfriend and two others in a Billings train yard

when her uncle dared them to jump onto the passing train. Little

Sun took the dare.

"I was superwoman," Little Sun says. "I remember

my feet hitting the ground, then my neck snapped back and I blacked

out."

When she regained consciousness, Little Sun was lying next

to the train. Her arm was still attached at the bone, but the

muscles and tendons were mangled. Her fingertips hurt. She kept

trying to get up, but the others wouldn't let her. As her mother

screamed in the background, Little Sun called out for her grandmother.

Little Sun woke up in the hospital. Her arm was gone, but Mae Whitedirt was there, as were her other grandparents.

"Then they all started fighting," she remembers.

"They thought it was my mom's fault. It was my fault."

After two weeks in the hospital and two more months in rehabilitation,

Little Sun was back on her own. The hardest obstacle to overcome

since losing her arm has had nothing to do with picking up a

pen or a fork. Little Sun had to listen to the cries of Darlyn,

born four months after the accident, because she couldn't lift

her up to comfort her. But Little Sun eventually learned how

to pick up her daughter. Her aunt, Elrena Whitedirt, says Darlyn

began helping her mother by lifting herself up to be changed

and holding her own bottle when she was just an infant.

Little Sun says that in a way, the wheels of the train that hit her in Billings started moving when her father died of leukemia in 1984. After that, her once devout mother stopped going to church and started drinking.

"My mom went downhill real bad," Little Sun says.

She and her four brothers and sisters were left for her grandmother

to raise, and Little Sun dropped out of high school in the 10th

grade.

Little Sun started drinking. She still does. And so does her mother. She doesn't think she has a drinking problem. "Sometimes I just can't handle some things," she says.

"I went to Job Corps to be a heavy equipment operator. I can't do that now. I want to get a high-paying job. I want my daughter to have a better life than I did."

Her voice trails off. She is currently on a waiting list for

federal housing and is living in Lame Deer with her grandmother

Mae Whitedirt.

Indians are 674 percent more likely than non-Indians to become

alcoholics, the Indian Health Service reports.

Elrena Whitedirt thinks the Cheyenne are turning away from their culture, and that this is to blame for the deaths and the drinking.

"People just aren't bonded together," she explains.

"They just kind of forget about each other."

Mae Whitedirt can't forget. Neither can Ledeana Little Sun.

When Dr. Margaret Grossman of the Indian Health Service came

to Lame Deer almost five years ago, she says a priest told her

to expect a funeral every week on this reservation of 7,000 Indians.

She has since drawn many comparisons between reservation life

and inner-city street life, where poverty is also pervasive.

Statistics show that 48 percent of the residents of the Northern

Cheyenne Reservation live below the poverty line, compared to

12 percent of Montanans statewide.

Grossman thinks that the indifference that springs from poverty

is to blame for the high death rates. This indifferent, hopeless

attitude often leads to drinking and drug use that is associated

with many deaths, she says.

She's seen families like Whitedirt's, and knows that death

does not discriminate. "I don't think there is any family

who has been missed," she says.

Emma Harris

is one mother who knows what drug and alcohol abuse can do to

a family. On New Year's Eve 1991, Harris' daughter Tonya Killsnight

came home after a night spent drinking with her friends. She

hugged Harris, wished her a happy new year, and passed out on

her bed. When Harris awoke the next morning, Tonya was gone.

Several days later, Tonya's frozen body was found near the Lame

Deer School.

By the time she was 18, Harris had had three children. Her own childhood ended at 13 with the birth of her first son, Delano. Christopher followed. Tonya was both her baby and her best friend. Harris admits she wasn't a good mother. She drank and took drugs, she says, admitting she even sold them. But in November 1991 Harris left the reservation for treatment. Mother and daughter agreed that when Harris was released Tonya would enter a treatment program.

Two weeks after Harris came home Tonya was dead.

Harris has stayed sober since her daughter's death and has

turned to helping troubled children. She started working at the

Lame Deer Boys and Girls Club in 1993 and now works in the 4-H

program. Harris says the job helped her find her way, and helped

her give kids the help she couldn't give her daughter.

" They are looking for some place to fit in," she

says of the children. "They want to feel safe and secure."

Harris is trying to make amends for her earlier failures at

motherhood. She has reestablished a relationship with her boys,

and says she realizes how her own troubled youth kept her from

addressing her children's needs because she was concentrating

instead only on herself.

"I thought I was robbed," she says of her childhood.

"When I was 14 years old I started working."

Shortly after Tonya's death, Harris became a foster mother.

Her foster daughter, Heather, has been with her seven years,

and Emma is hoping to adopt her. She sees Heather as her second

chance.

Yet many residents of the Northern Cheyenne Reservation don't

get that second chance.

Nurse Nikki Lippert of the Lame Deer Indian Health Service

wants non-Indians to understand that the high death rates there

and on other reservations are about more than just statistics.

"This is just a reflection of society," she says. "This doesn't just happen in Lame Deer."

|

|

|

| Tonya Killsnight is buried at the Harris family ranch a few miles from Lame Deer. |

|

| Mae Whitedirt struggles to remember stories of her family and her children's passings. |

|

| Ledeana Little Sun shows what is left of her amputated arm. |

|

| Emma Harris hugs her foster daughter. |

|

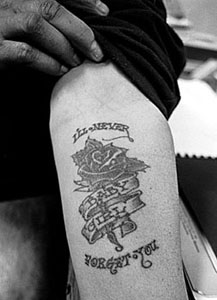

| Harris has a visual reminder of her daughter's life. After Tonya died, Harris got two tattoos to serve as a constant reminder of Tonya. Her other tattoo reads: "Fly to the angels," her daughter's favorite song. |