(Left) The first treaties – 1851 – 1855 | (Right) Current boundires

Evolution of Indian Territories in Montana

Cartography & Story by Amelia Hagen-Dillon

Traditional Homelands of Montana Tribes

The beginning of treaties

Some forty years after Lewis and Clark explored the area that is now Montana, the number of white settlers passing through the region began to increase dramatically. Settlers were motivated by the prospect of cheap land and the promise of gold further west in California. In 1851 Congress passed an Indian Appropriations Act which allocated money for creating and moving Indians onto reservations. The federal government had already begun confining Indians to reservations in the eastern states and as more settlers moved west they began to do the same in the west. In the 1850s the U.S. Government entered into their first treaties with tribes living in what is now Montana, and while the government did not confine all the Indians to reservations immediately, those early treaties laid the groundwork for the reservations that exist today which are tiny fractions of (and in some cases thousands of miles from), tribe’s ancestral homelands.

The Treaty of Fort Laramie

In 1851 the U.S government negotiated a treaty with the tribes living on the Northern Plains hoping to ensure safe passage for the settlers traveling through and to reduce fighting between tribes. The treaty was signed in September 1851 by representatives of the Cheyenne, Sioux, Arapaho, Crow, Assiniboine, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes. The treaty set forth territorial claims as they were understood by the U.S. government representatives and agreed upon by representatives of the tribes. Importantly the U.S government did not make any claim to ownership to any of the land covered by the treaty. The federal government asked for safe right of way for the Oregon Trail and that the tribes allow roads and forts to be built on their land in exchange for an annuity in the amount of $50,000 for 50 years, which was later changed to 10 years when the treaty was ratified by Congress.

West of the Divide

The Treaty of Fort Laramie did not concern territory west of the Continental Divide, then part of Oregon Territory. The Kootenai, Pend d’Oreille and Salish continued to live in that region as they always had. As more settlers moved to the area in the first half of the 19th century the U.S government got more involved.

U.S. Border

In 1846 the United States and Britain signed the Oregon Treaty which resolved the dispute over the boundary between their territories from the west coast east to the Continental Divide and set that boundary at the 49th parallel. An earlier treaty in 1818 had established the boundary from Minnesota west to the Rocky Mountains as the 49th parallel. The new international border split the territories for many tribes but people continued to move freely back and forth across the border.

In 1853 Oregon Territory split in two and the northern half, which included present-day Northern Idaho and Western Montana, became Washington Territory.

The first Treaties – 1851 – 1855.

1855– Blackfoot Peace Treaty

Just four years after the Fort Laramie Treaty, new treaties were negotiated with tribes of the region. The Blackfoot Peace Treaty (also known as the Lame Bull Treaty) signed by the Blackfeet, Gros Ventre, and Assiniboine and attended by thousands of members of other tribes from east and west of the Continental Divide including the Flathead (Bitterroot Salish), Pend d’Oreille, and Kootenai, but not the Crow. Tribal leaders signed an agreement confirming non-overlapping territories and creating shared hunting grounds. The Blackfeet agreed to share the Three Forks area (Missouri headwaters basin) with Western tribes and the area east of the Milk and north of the Missouri Rivers with the Assiniboine in exchange for $20,000 worth of goods delivered annually. The signees agreed to maintain peace and permit settlers to live and travel through their hunting territories and for roads, telegraph lines, military posts and Indian agencies to be built. As with the Fort Laramie Treaty no tribes ceded ownership of land to the U.S. government under the Lame Bull Treaty.

1855- Hellgate Treaty

West of the Continental Divide was another story. Isaac Stevens, the governor of Washington Territory, spent ten months traveling through his territory negotiating treaties with the tribes living in the area including the Bitterroot Salish (Flathead) the Pend d’Oreille, and the Kootenai. The tribes ceded most of their territories to the United States and agreed to live on the “Jocko Reserve”– today’s Flathead Reservation– and reserved the Bitterroot Valley as a “Conditional Reservation” where the Salish continued living. It was said the language barrier was so great that less than a tenth of what was agreed upon was understood by the tribal leaders.

States and Territories

Oregon became a state with its current boundaries in 1859. The remainder of Oregon and Washington territories, including the part of present-day Montana that is west of the Continental Divide became Washington Territory. East of the Divide Montana was part of Dakota Territory, then briefly part of Idaho Territory, before being organized in 1864 as Montana Territory, with its current boundaries.

1860s Declining Bison, Disease, and Building Conflict

Inter-tribal conflict and conflict between tribes and white settlers in the upper Missouri region, coupled with declining bison populations and disease epidemics lead to shifting and re-aligning of tribes in the upper Missouri basin. Gold discoveries in the Northern Rockies brought thousands of miners by 1865. The Sioux wars, a series of conflicts between tribes and the federal government over the government’s failure to pay promised annuities and increased white settler presence in Indian territory began in the 1860s and continued for over a decade.

Shrinking Blackfeet Territory

In 1865, in the face of various pressures, the Blackfeet agreed to sell 2,000 square miles of the territory south of the Missouri River claimed by them in the Treaty of Fort Laramie to the U.S Government. The treaty marking this sale was never ratified by Congress but settlers began moving into the area anyway.

Assiniboine

In 1866 the Assiniboine agreed to cede the area designated to them in the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty to the U.S. Government. The treaty was never ratified but some Assiniboine moved to Fort Belknap and Fort Peck

In 1868 the Second Treaty of Fort Laramie established the Great Sioux Reservation in western South Dakota. The area north of the North Platte River and east of the Bighorn Mountains was reserved as “unceded Indian Territory” and was occupied by the Northern Cheyenne.

Crow Reservation

In 1868 the Crow agreed to sell about 30 million acres of the territory designated to them in the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty and agreed to live on a smaller reservation south of the Yellowstone River in what is now eastern Montana.

(Left) 1860’s | (Right) 1870’s.

1870s- Redefining Relationships

Indian Appropriations Act

In 1871 when Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Act, they redefined the U.S. government’s approach to their relationship with Indian tribes. The federal government ceased to recognize Indian tribes as fully sovereign nations and thus stipulated that rather than making treaties with tribes, the relationship should be governed by statutes passed by Congress. The Act transformed the relationship between the federal government and Indians from a government to government relationship to one of guardian and ward.

“That hereafter no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty: Provided, further, That nothing herein contained shall be construed to invalidate or impair the obligation of any treaty therefore lawfully made and ratified with any such Indian nation or tribe.” -From the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act

Great Northern Reservation

In an executive order in 1873 the U.S government claimed ownership of large parts of what is now central Montana. The order established the Great Northern Reservation for the Blackfeet, Gros Ventre, Piegans, and River Crows with the same southern boundary established by the unratified 1865 treaty. Fort Belknap and Fort Peck were established for distributing annuities.

The prime grazing lands for Blackfeet south of the Marias River were taken by an executive order by President Grant in 1874. The following year another executive order restored some of that land to the tribes. In 1880 yet another executive order took the land back.

Northern Cheyenne

In 1877 the federal government forced the Northern Cheyenne to move from their traditional territory in the plains of Wyoming, western South Dakota and southern Montana to present-day Oklahoma to live with the Southern Cheyenne. In 1878 a small band escaped and made their way north to join relatives of theirs who had stayed behind. They settled briefly near present-day Miles City before moving to an area south of the Yellowstone River along the Tongue River, east of the Crow Reservation.

Assiniboine

In 1875 the Assiniboine territory assigned in the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty officially fell under U.S. domain. The Assiniboine were sent to live at Fort Belknap with the Gros Ventres and to Fort Peck to live with the Sioux.

In 1876 The federal government closed Fort Belknap and tried to force the Gros Ventre and Assiniboine to move to Fort Peck. Many Assiniboine went but the Gros Ventre did not get along with the Sioux who were at Fort Peck and refused to go. In 1878 Fort Belknap was re-established.

Statehood and the end of Bison

Bison

In the early 1880s the Blackfeet had back to back years of unsuccessful bison hunts. There were essentially no more bison in the Northern Plains which left the Indian tribes in the region entirely dependent on government annuities. Compounding the near-extinction of their primary food source were diseases like smallpox and scarlet fever which killed thousands of people.

Sweetgrass Hills Treaty

In midwinter of 1887, when many tribal members could not attend the council, the Great Northern Reservation was split into three much smaller reservations and 17.5 million acres were ceded to the U.S. Government. The Blackfeet reserved their reservation on the far western edge of their original treaty territory. The Gros Ventre and Assiniboine agreed to live on Fort Belknap reservation south of the Milk River and the Sioux and Assiniboine near Fort Peck agreed to the current boundaries of the Fort Peck Reservation.

Statehood

In 1889 Montana, North and South Dakota, and Washington became states. Wyoming and Idaho followed in 1890. With the formation of new states, the U.S. tacitly claimed ownership to the remaining unceded Indian Territory

Crow and Northern Cheyenne Reservations

In 1882 under pressure from white ranchers, the railroad, and federal officials, the Crow tribe sold the westernmost part of its reservation to the U.S. Government.

In 1884 the Northern Cheyenne reservation was established from territory that previously belonged to the Crow tribe.

In 1892, following crop failures and under pressure from gold prospectors in the Absaroka Range the Crow sold another piece of their reservation.

Bitterroot Conditional Reservation

In 1891 Chief Charlo and the last of the Bitterroot Salish living in the Bitterroot Valley were forced to move to the Flathead Reservation, known as the Montana Trail of Tears.

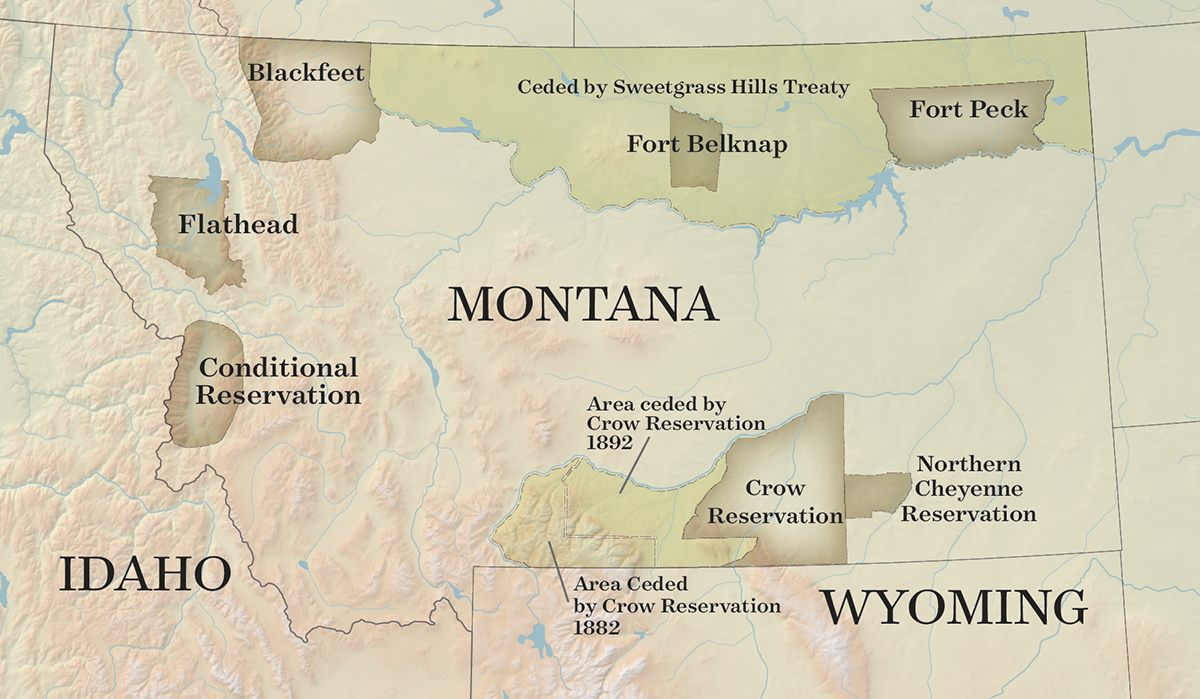

(Left) 1880’s | (Right) Current boundaries.

1890s

Allotment

The Allotment Act, also known as the Dawes Act, which passed in 1887, allowed for tracts of land within existing reservations to be divided up between members of the tribe and for the remaining reservation land to be opened up to homesteading by white settlers. Up until this time the reservations had been held communally by all members of the tribe(s) living on the reservation.

Federal officials reasoned that if Indians adopted land ownership and agricultural lifestyles they would assimilate into the population and then the U.S. government wouldn’t have to pay annuities anymore.

The Act and subsequent acts opening other reservations to allotment resulted in the transfer of millions of acres of tribal land to individual ownership and resulted in a loss of more than 90 million acres, or nearly two thirds of tribal land across the United States. Even land holdings gained by individual Indians were often lost to non-Indian ownership.To this day large portions of many reservations are owned by non-tribal members. Exceptions in Montana include Northern Cheyenne, where the tribe was able to maintain control of allotments to a large extent, and the Rocky Boy reservation, which was not yet established.

Blackfeet — the Ceded Strip

In 1895 the U.S. government claimed 800,000 acres along the western edge of the Blackfeet Reservation. The northern half of this part of the Rocky Mountains, the “Backbone of the World” to the Blackfeet, became Glacier National Park in 1910. The Blackfeet, after days of refusing to sell, finally agreed to sell the land for 1.5 million dollars with the agreement that the reservation would not be subject to allotment. It later was, however.

Rocky Boy’s

The Chippewa arrived in Montana in the 1880s and lived a nomadic lifestyle roaming around the central part of the state. They banded together with a group of Cree in the early 1900s. In 1909 the government tried to force them to move to the Blackfeet Reservation. Living conditions there were not good so most of them left. They petitioned the government for a reservation of their own several times and in 1916 President Wilson created Rocky Boy’s Reservation for the Chippewa Cree and other reservation-less Indians.

Gold in the Little Rockies

When gold was discovered in the Little Rocky Mountains on Fort Belknap Reservation miners staked claims on tribal land. In 1896 George Bird Grinnell negotiated an agreement with the tribes where Fort Belknap agreed to sell a portion of their reservation to the federal government.

Northern Crow

In 1904 a congressional act reduced the size of the Crow reservation, claiming the northern part and shrinking it to its current boundaries. The tribe did not receive a lump sum payment for the land they gave up but they did receive funds for horses, cattle, sheep, irrigation, and school buildings.