Story by Ryan OConnell | Photos by Graham Gardner

Rocky Boy’s

Trey Stiffarm swept his dark hair, cut just above his brown eyes, across his forehead. His earbuds, likely playing any mix of hip-hop, rock or classical music, swung across his grayscale, western snap-up shirt as he shifted in his chair. He leaned forward, hands on his knees.

Stiffarm is the mechanic for Rocky Boy High School’s robotics team. As the team’s main assembler, it’s his job to find quick solutions. He joked that he likes when the robot is finished and actually functions. “My favorite part is probably the wiring,” he said. “Just be sure to zip tie them.”

He’s busy visiting schools, planning for next year: Rocky Mountain College, Montana State University Billings and, most recently, Salish Kootenai College. If he goes with SKC, he plans on transferring to the University of Montana and majoring in business. After college, maybe he’ll use his mechanical knowledge working on cars or run a restaurant. But he’s keeping his options open.

Stiffarm nods with his whole body. He has a quick-draw smile that can be holstered as fast as it appeared.

“It’s kind of a lot to talk about,” Stiffarm said. He’s guarded, impenetrable. His tongue tastes every word.

It’s a difficult subject. Especially for a high school student.

“Most kids don’t have stuff in their cupboards, you know? Just dust,” he said.

Many residents on the Rocky Boy’s Indian Reservation participate in federal and state aid programs. However, it’s these very programs that have been under a microscope in the last year.

In January, for instance, President Donald Trump suggested cutting the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which gives recipients a monthly allotment to purchase specific food items. Trump suggested instead the government give out boxes of preselected food, a program not unlike the existing commodities food program.

The proposed 2019 national budget cuts SNAP by $213 billion over the next 10 years.

The budget also cuts the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program nationwide, specifically $4.5 million in Montana alone.

The truth is, even before any program cuts, commodities run out and monetary assistance doesn’t stretch as far here where necessities cost more and the closest supermarket is 30 miles away. Indian Country has known need for a while though, which is why a student-led grassroots program on Rocky Boy’s reservation is addressing issues like hunger and poverty directly.

Inside a repurposed chemistry classroom, Jillian TopSky looked up from her paperwork, pen in hand, and shouted, “Hey, guys! Remember to give them broccoli.”

Students in the room groaned, but everyone in Rocky Boy’s Helping Hands program got broccoli.

At the end of the school week, students at Rocky Boy Public Schools are given backpacks or totes full of food, hygiene essentials and household supplies through the student-run Helping Hands program.

Grassroots efforts led by students are our “boots on the ground,” said Stephanie Stratton, chief program officer at the Montana Foodbank Network. MFBN supplies boxes of prepackaged food for 116 school districts. Usually, a local non-profit organization partners with a school to fund the $40 boxes. Rocky Boy school district is one of 12 districts where a non-profit has not provided assistance. Individual efforts are a huge part of Helping Hands’ success. Student volunteers have stepped up.

TopSky, a senior, started the program as a sophomore after learning about the Montana Governor and First Lady’s fight childhood hunger initiative. Her student advisor and English teacher, Kristiny Lorett, asked TopSky and another student what they wanted to do with a grant given to Rocky Boy’s schools.

Organizing a one-time canned food drive or a schoolwide dinner wasn’t enough. TopSky had heard of other schools participating in backpack programs and they decided to start their own.

“We thought this was the best idea that would impact our school in the biggest way,” she said.

Kristiny Lorett and Jillian TopSky shop for basic food items at Walmart for students as part of the Helping Hands program. Havre, Montana, March 3, 2018.

TopSky’s eyes are squared off by dark framed glasses and she wears a small St. Mary’s pendant strung through by rawhide around her wrist or as a necklace depending on her outfit. Her mother made one for her and each of her five sisters.

She recounted a story an older sister told her. At the time, the sister’s boyfriend was caring for his brothers and sisters. Their mother was absent. Their home was isolated. They had no electricity and no food. They ate as much as they could at school before going home.

“It shouldn’t be like that. There has to be a solution to this,” TopSky said.

Poverty is common on Rocky Boy’s. A 2015 Montana State University study put the poverty rate at 41 percent, an increase of 4 percentage points since 2012. The average rate on Montana reservations was 31 percent.

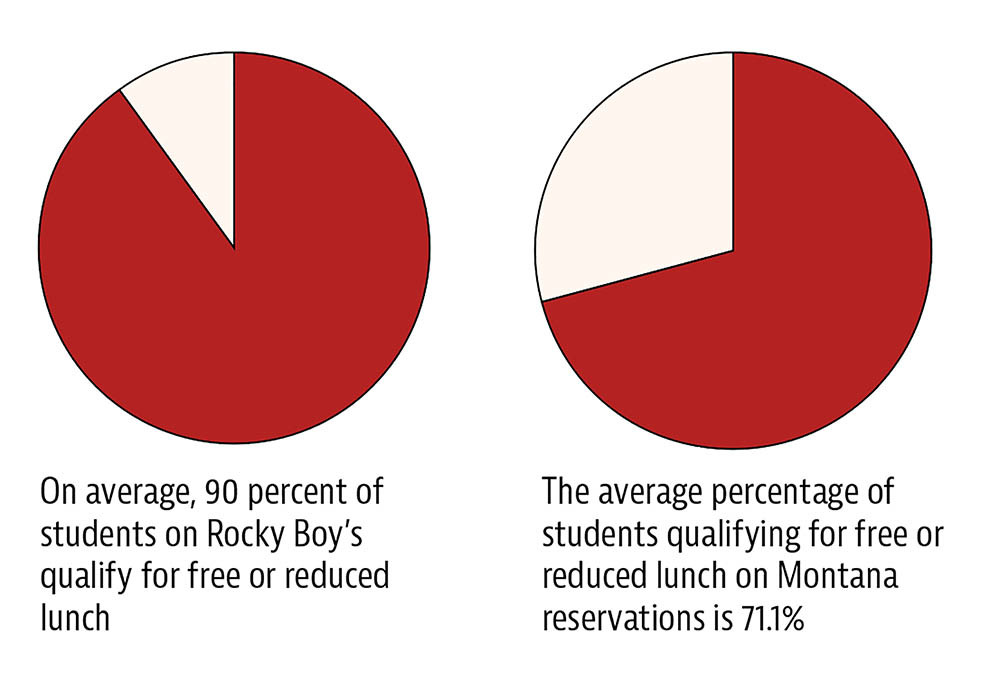

A 2017 MSU report found that 92.7 percent of students at Rocky Boy Elementary qualify for free or reduced lunch. Rocky Boy junior high and high school data was not released due to privacy concerns, but was estimated by the administration to be 89 percent.

Based on available data, the average percentage of students qualifying for free or reduced lunch on Montana reservations is 71.1 percent.

Stiffarm, a senior, was one of the program’s initial students. He said the Helping Hands program not only benefits students, but also families. He and his sister both receive a backpack. They discuss what their family needs before submitting request forms.

He said the extra food and supplies let him concentrate on school and eases the stress on his family, especially at the end of the month.

John Mitchell, with the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations, said 187 households are registered with the program but the amount of food provided often doesn’t cover a household for a full month.

Participation in SNAP on Rocky Boy’s Reservation increased from 38.6 percent in 2012 to 44.5 percent in 2015. The 2015 rate is double the rate experienced by residents of all reservations.

Households cannot receive aid from both SNAP and the food distribution program concurrently.

Stiffarm’s family receives SNAP benefits, but they do not have a car, which makes grocery shopping difficult. A ride to Walmart in Havre is optimal, but they are usually forced to go to Gramma’s, a grocery on the reservation where government benefits don’t hold out as long.

Every dollar counts.

Jillian TopSky, the Rocky Boy High School student who started the Helping Hands program. Havre, Montana, March 3, 2018.

Cheap and bulk. “That’s our motto,” said TopSky as she and Lorett began loading bottles of shampoo and conditioner into their first shopping cart.

They chose Windblossom scent over Strawberry, a student is allergic to strawberries.

Thirty-six bottles of shampoo and conditioner, 20 aqua colored dish soaps, eight bags of laundry pods.

TopSky ran her hand behind a hanging display of bobby pins and pulled a dozen packs into the cart. An arm’s length of hair ties followed.

The Walmart Foundation gave the Helping Hands program a $10,000 grant. TopSky and Lorett travel to Havre every other week to stock up on supplies: typically, generics or sale items. Vaseline laid at the bottom of the cart with Walmart’s Equate brand.

Twenty-one lotions packaged in white, blue or seafoam green, 19 two-packs of toothpaste.

Lorett confidently pushed her cart forward. TopSky’s cart picked up speed before she leaned up on the handlebar, her feet sliding across the concrete toward the tea aisle.

Sixteen bear-shaped honey bottles, nine non-bear honey bottles, five boxes of 30 bags of cookies and crackers.

In their wake, the honey shelf needed restocking. Same with the tampons and hand soap. Blotches of orange, grapefruit pink, aqua blues and soft greens refracted through the shopping carts’ wire frames.

Forty-eight bottles of hand soap, 17 boxes of tampons, 14 boxes of pads.

At the register, TopSky ran back for 98-cent reusable shopping bags. The program tries to get students to bring bags back after the weekend with food incentives, but isn’t always successful. Eighteen reusable shopping bags are the last items across the scanner.

From the first shampoo hitting the conveyor belt to the cashier handing over the receipt took just under 19 minutes. For larger expenditures, four or five carts, a 40-minute transaction is common.

This trip’s total was $643.58. Lorett estimated the Helping Hands program spends up to $1,600 a month.

TOP: Kade Galbavy stands next to a cart of prepped bags ready to be handed out to students. Rocky Boy’s reservation, March 3, 2018.

“More students qualify for the Helping Hands program than don’t,” Rocky Boy High School Principal Deborah LaMere said.

Both Rocky Boy Elementary and Rocky Boy High School are Title I schools. Title I provides financial assistance to school districts with children from low-income families.

Schools must focus the money on children who are in danger of failing unless at least 40 percent of children enrolled come from low-income families, then the funding may be used schoolwide. Rocky Boy Public School system qualifies for schoolwide use of Title I funds.

LaMere said the state’s school lunch program is never fully funded and by pursuing grants, the school district does a good job providing students enough nutritious food to eat during the day.

Dinner and the weekend can be a challenge.

“From freshmen all the way through senior class, we’re going to have students helping the backpack program as an ongoing thing for not [just] next year, but to keep doing it year after year,” LaMere said.

At the end of the day, 55 students went home with supplies to help them and their families.

“I don’t think [student volunteers] think of it as responsibility as much as I think they really enjoy doing it and helping other students,” LaMere said.

The more active Rocky Boy’s students are, the more opportunities they have. Community service increases eligibility for scholarships and sponsored trips.

The American Indian Business Leaders club will use the program to represent themselves at the AIBL national convention in Arizona.

TopSky went to Billings in March for Montana’s Family, Career and Community Leaders of America where her Helping Hands program won second place and an invitation to the national convention in Atlanta this summer.

She’s undecided what she’ll be studying at the University of Montana this fall.

“This program is only a small part of our community and it’s doing a small part in our school,” TopSky said, her hands swirling and corralling her words, “but this is the foundation where students involved in the program, for students that are going to commit their time, this is a great experience to start out for their future.”

The Helping Hands storeroom had a muted smell of warehouse cardboard. The program started by handing out plastic Walmart bags from the corner of a small office. Now, they’ve overrun a chemistry room.

Behind transparent cabinet doors: Essentials of Anatomy & Physiology and Science Experiment Sourcebook. Empty drawers were labeled “Mortar + Pestle” and “Evaporating Dishes.” Dissection kits were tucked in cabinets like Russian dolls.

Freeze-dried fruit, broth (beef and vegetarian), and crackers were stacked on the floor. Chex cereal boxes flirted with the drop-down ceiling. A yellow emergency shower head and dinner triangle pull tab peeked over a column of boxes from the Montana Food Pantry. There were over 90.

The merchandise from yesterday’s shopping trip had been laid out. A 20-foot long island was laden with red salsas, protein bars, penne pasta, soup. The sink brims with bags of laundry pods and toothbrushes.

TopSky and four other students moved supplies and broke boxes. Organizational questions were directed at her. Where should this go? What next?

It’s all about “finding spaces and throwing stuff in corners,” TopSky said. She used a green comb to slice through a stretch of tape before collapsing a box and frisbeeing it across the room.

The room was hot, but the window was hemmed in by three stacks of boxes 12 high.

“I don’t want them to feel embarrassed,” Kristie Parker said. She clasped her hands together. Her nails were painted sky blue, the cultural color she was given at birth.

Parker, a junior helping run the program next year, was concerned about privacy. She wanted to increase confidentiality to encourage more students to utilize the program.

Trey Stiffarm said students may be too shy or embarrassed to use the program. A lot of students, including him, were raised with a cowboy mentality, he said. If you need something, get it yourself.

It was hard to ask for help. “I just did it, I just asked,” he said.

Students fill out a weekly request form to receive a backpack. Parker and fellow student Zane Parker recently revised the form to provide more privacy. The form requires the student’s name, grade, allergy concerns, number of siblings living with them and if they have electricity. The previous form asked for their siblings’ names and ages and if their family was receiving government aid. After the list of available items: is there anything else you’re in need of right now?

Junior high and high school students put their locker numbers at the bottom of the form. The lockers do not have locks, and at the end of the day students find their requested bag inside. Elementary students’ bags are transported in a collapsible blue wagon and arranged in the office.

The junior high and high school share one building, the elementary school is in another. They’re connected by locker lined hallways, concrete paths, encouraging teachers and students who spend their academic careers crossing the same faded basketball court.

The Helping Hands program has had challenges. Time is a major factor. Besides the backpack program, TopSky is involved in the AIBL, Rocky Boy’s Youth Council, volley ball and AP classes.

Other volunteers divide their time between the program, school work, AIBL and sports.

Students have taken advantage of the program. There have been needs vs. wants conversations. TopSky said some students don’t appreciate the work put into the program and food has been played with, left behind or thrown away.

Before school is let out, two seafoam green bottles of lotion have been smashed in the parking lot; run over, the cream lotion amoeba contrasted with the grainy asphalt.

“I feel overall,” TopSky said, “that all programs have people take advantage of it, not appreciate it, but kids that do need it and kids that are benefiting from it outweigh the ones that are taking advantage of it.”

Trey Stiffarm seems to fall into the latter camp, recognizing his family’s needs.

“It helps me a lot,” Stiffarm said, “helps my family out a lot.” His mother uses noodles and sauce to cook spaghetti for family dinners. Dish soap, toilet paper and tissues make a difference.

“Most kids probably never had tissues. Tissues, it’s not in our budget,” he said.

Stiffarm is suspicious of outsider intervention. The notion that white people’s historic treatment of native populations can be atoned through commodity food and suspect good will is laughable.

The program’s expansion has been fast. Grassroots fundraising, teachers donating food or $5 to wear jeans on Wednesdays and Superintendent Voyd St. Pierre’s back to school BBQ, has led to corporate grants and national recognition.

Teachers and community members still donate but more volunteers and funding are needed for the program’s future. There are plans to move request forms online and begin nutrition programs and cooking classes. A greenhouse is being erected out back.

The overall community awareness is reflected in the school’s bathrooms. Stickers placed on the boys’ bathroom mirrors are regularly replaced as letters are scraped away: YOU’RE LOVED, YOU’RE BEA TIFUL, OU’RE MAZING.

TopSky wants to see the program expand to Box Elder High School, 13 miles away. It is not uncommon for cousins to face off in cross-town basketball games: Rocky Boy North Stars vs. Box Elder Bears. She sees the program tying the community together.

During an assembly for statewide backpack day, the Helping Hands volunteers led the gymnasium in a cheer. It was awkward at first, silly, but by the third run through, students were clapping along, shouting:

Helping Hands help each other,

Let’s go Stars, all together

Go Stars!