Story by Alex Valdez and Bjorn Bergeson, photos by Kylie Richter

On 80 acres nestled up against the Mission Mountains lives Tim Orr. He grew up there, bought the tract of land from his father after graduating high school when he was 18.

He’s 59 now, an irrigator, grows grain and alfalfa and raises 65 cows. In his house, there are shelves with green miniature John Deere tractors. Sporting his rainbow suspenders, and a neatly trimmed white beard, he points to photos of his children and grandchildren, covering his refrigerator.

On the fridge, a particular magnet stands out. It’s a big red circle with a slash through one word: “Compact.”

Orr is a member of the Confederated Salish Kootenai Tribes. He is also one of a few tribal members against the Confederated Salish-Kootenai Tribes water rights compact, which dictates water usage between the tribe and both the state and federal governments. From the beginning, Orr has not supported the compact, and his opposition has cost him.

He said he has been accused of being racist. He said he has even lost land leases to the tribe because of his involvement with the Montana Water Users Association, a controversial group that staunchly opposes the compact.

“The council came up with the policy that anyone who has anything to do with the Western Montana Water Users won’t lease tribal ground,” Orr said.

The water rights compact has divided the Flathead Indian Reservation, pitting neighbors, friends and the community as a whole against one another over the struggle to decide who controls the rights to water sources both on and off the reservation.

On the edges of the fight there is litigation, confusion, frustration, and allegations of racism. In the middle of the fight are the irrigators—some tribal members, others who aren’t—who rely on the water for agriculture, the political activist groups, and the Confederated Salish-Kootenai tribes.

And at the center of it all, the echoing question: Who owns the water?

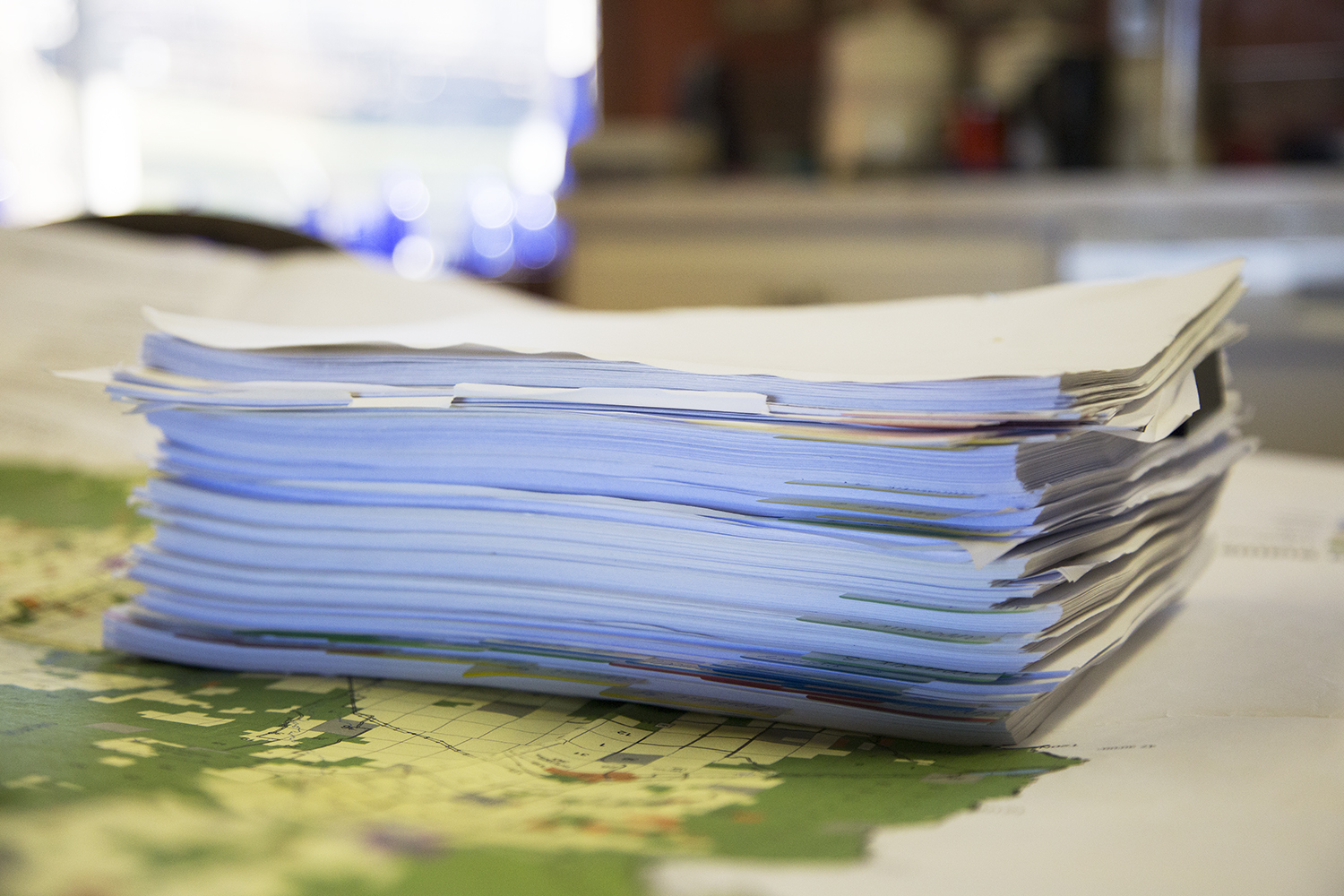

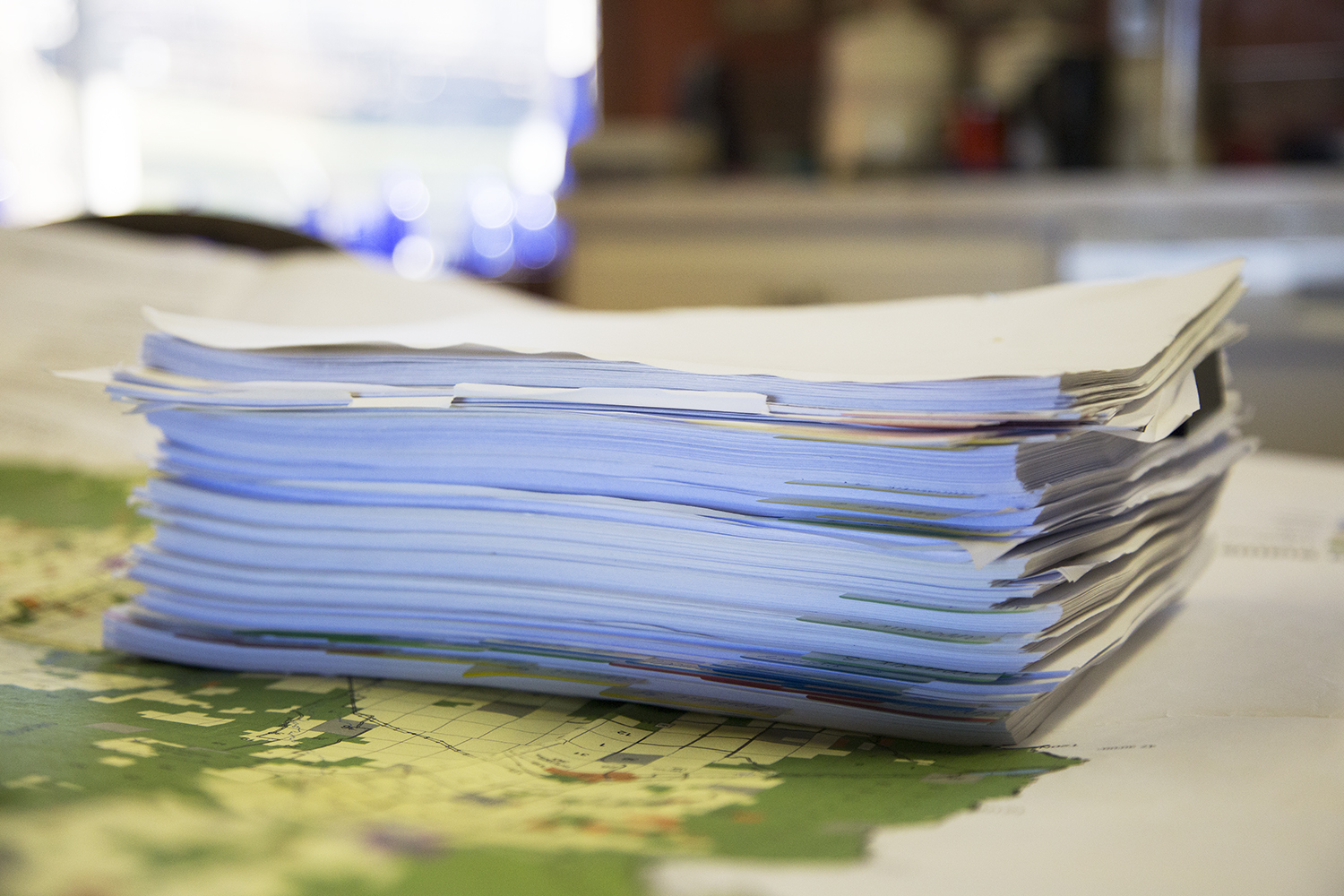

At a table covered with maps and the 146 pages of the compact, Orr listed his three main problems with the water deal. He fears the tribe will strip away property rights from individuals and give them over to the tribe. He said it will cut in half the water he has historically used and remove irrigators from the Montana Water Court system. A move he feels is unconstitutional.

Enlarge

Orr sits on the Flathead Joint Board of Control, a state-chartered regulation group that oversees irrigation water on the reservation. While some members of the board have supported the compact in the past, the board has generally fought against it. Organizations on the tribe stand with them, though some of the groups against the compact have alleged ties to known anti-Indian groups.

On the 24th of April, six days after the state legislature passed the water compact, the board of control launched a lawsuit against the state of Montana, declaring it unconstitutional because the proposal did not meet the a two-thirds approval.

In Orr’s opinion the compact will diminish property values. He said people trying to buy irrigation land wouldn’t know how much water is available to them, making the property less desirable for future agricultural development.

“I will be a less than average farmer because this gravel ground that I live on will dry up,” Orr said, adding that he believes if the tribe controls the water as the compact would allow, the tribe will drive his irrigation water down by half, reducing his ability to produce at the same level he has in the past.

“This grass right here, it’s starting to grow,” Orr said. “When it runs out of water it will shut down and that alfalfa out there will shut down. You’re going to cut your production. When the grass stops growing the calves are going to run out of feed, so the calves will stop growing.”

For Orr, the fight over the compact has everything to do with preserving the land he and his family have lived on for over a hundred years. But some on the reservation see the opposition to tribal control of water as one more push against the tribes. The motivations behind it smack of ignorance and racism that can be traced back over a hundred years.

PATRICK PIERRE, a Pend d’Oreilles Native American, and tribal elder, was involved in the water compact negotiations from the start. It took years to reach a workable compromise between the tribe, the state and the federal government, and overall it is the tribe who gave up the most to secure the deal, he said.

Some see the compact as a veiled power grab on the part of the federal government, using the tribe to take land and water from non-tribal residents and keep it under federal control rather than state. Others see it as a power grab on the part of the tribe itself.

“A lot of people opposed it because they thought they would lose their rights, no one lost anything,” Pierre said. “It’s beneficial for the whole state of Montana.”

The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes are the last in the state to have a water compact with the U.S. Government. The compact established and defined the tribe’s water rights. The root of the compact goes back to July 16, 1855, when the Salish and Kootenai tribes signed the Hellgate Treaty, which not only established the reservation, but specifically enshrined access to almost all the water in Montana west of the continental divide, both on and off the reservation. The treaty promises the tribes will have these rights for “time immemorial.”

Enlarge

With the compact, the tribes will have rights to water in 11 counties in Montana, and a large chunk of the headwaters west of the Continental Divide in the state. The amount of water granted to the tribes through the compact is much less than what the tribal government could claim rights to if they stuck to the letter of the Hellgate Treaty.

The Flathead reservation is a census oddity in Montana. Home to over 28,000 people, only 5,000 of which are enrolled tribal members. Another 3,000 enrolled members live off the reservation. Flathead may be the most populated reservation in Montana, but non-natives outnumber Native Americans more than five-to-one. Many who oppose the compact are white landowners living on the reservation.

“There’s a little thing called racism,” Pierre said. “There are a lot of people right here on the rez that don’t really get along with Indian people. They just don’t want the tribe to have control of anything. They want it all. That’s one of the things that they never say, ever.”

Orr disagrees that race played into the Board of Control’s opposition to the compact. Instead, he wants to refocus the argument against the compact using constitutional rights.

“It’s not against the Indian people,” Orr said. “It’s against this compact and the tribal government. That’s the only thing we oppose. We’ve said that since the beginning.”

Jerry Laskody, the board’s chair, said the compact is essentially theft on the part of the tribal government. But he doesn’t see the fight against it as a racially motivated issue.

“I’m sure there are people that are very racist around here but that’s not what we’re talking about,” Laskody said. “We’re talking about irrigation rights and the quantity of water that we’ve historically used and the fact that we don’t want to be treated differently than the rest of the citizens of Montana.”

ACCORDING TO the Montana Human Rights Network, racism takes subtler forms in Indian Country. They debate the constitutionality of the tribe’s sovereign governments, and advocate the abolishment of reservations under the argument of equal rights for all.

“These folks are opposed to the basic idea of tribal sovereignty and the equality and rights of the Indian people,” Rachel Carroll Rivas, co-director of the Montana Human Rights Network said. “Things have come out, things at public hearings and the legislature where there is a real inherent bias against Indian people and they bring that view to the fight.”

Rivas said the network decided to do a study on the compact due to the community response it was creating. The water compact passed the state legislature in Helena on April 16. The day before, the rights network released a report entitled “Right Wing Conspiracies and Racism Mar Opposition to Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and State of Montana Water Compact.”

The Flathead Indian Reservation has a long history of anti-Indian organizations. In the late 1980s and early 90s it was a hotbed for anti-government, anti-Indian groups, militias and white supremacists, Rivas said. According to the network, many of the same people who fought against tribal rights and sovereignty before can be found fighting the water compact now, still opposing Native American control of any land.

“We saw some of the same names that were then opposed to the tribes on various issues in the past including the bison range,” Rivas said. “In some ways it’s kind of like same story, same people, different issue.”

Rivas said activists in groups like Western Montana Water Users, and Concerned Citizens of Western Montana use veiled racism to soften their messages.

One of the groups the report focused on is the Western Montana Water Users. Tim Orr said his association with this group caused the tribe to single him out and take his leased land.

Not all the irrigators on the reservation oppose the contract. But the main argument hinges on litigation, which is both expensive and time consuming. Proponents of the compact focus on the stipulations in it to fix the aging infrastructure of the irrigation project and said the funding is ample enough to maintain water levels across the reservation.

Enlarge

The Flathead Joint Board of Control is funded through property taxes, and lawyers aren’t cheap, so the board has had to levy for tax dollars to pay for it all. And while the board of control has sued the state and tribe multiple times since the 1980s, they have always lost in court.

Always trying to settle the question: Who owns the water?

WHEN THE Flathead Joint Board of Control held its leadership election in 2013, Ruth Swaney, who at the time was a coordinator of a local Idle No More movement, turned up with a small group of tribal members to protest the involvement of Western Montana Water Users in the election process. The water users group had mailed a flyer out with Joint Board of Control ballots, urging voters to support candidates who were against the compact and admonishing those who were for it.

During the small demonstration in the parking lot, a flyer titled “12 Facts About Tribal Sovereignty” was distributed among the crowd.

The facts included: “On the Flathead Reservation, a resident can be one quarter French, one quarter Scotch, and one quarter Irish … and still claim that someone is racist if they disagree with you. (True, if also Tribal Member)”

And.: “The term ‘racism’ can be used as a slang term to instill, or claim, that there is racial prejudice or guilt on innocent American citizens that only seek fair treatment.”

The pamphlet was called a “racially targeted flyer” by the Car-Koosta News, the official news publication of the Flathead Indian Nation.

“No one wanted to own up to it, yet they wanted to pass it out,” Swaney said.

Swaney recalled an exchange with a member of water users group in the parking lot in front of a small crowd. She said she tried to argue against his logic concerning the compact, and what was written on the flyer. But at a certain point she realized she would make little headway.

“I’ve been listening to this sort of talk my whole life,” Swaney said. “So maybe I’m a little less sensitive to it now. On the other hand, I’m kind of losing my patience. I used to let some stuff slide and let people say what they say and just laugh. Now I say you know, ‘I’m tired of hearing you coming from your view point of not being informed.’”

Swaney is the budget director for the Confederated Salish-Kootenai tribes. She said many people are misinformed as to the nature of the compact. She’s lived in St. Ignatius for most of her life. While she doesn’t necessarily think that resistance to the compact is based entirely on racism, she said people choose to be ignorant of the facts surrounding the compact.

“I just sum it up, as people are really not educated at the most basic levels of what Indian people are about,” Swaney said. “People aren’t really that interested in finding out the full truths or the details. That’s what I call ignorance. You know: To ignore.”

She said the irrigators are irresponsible with water usage sometimes. For the most part they’ve gotten to do whatever they wanted and faced minimal repercussions for their actions.

“I’ve gone back and read some of our old tribal council minutes,” Swaney said. “They go back all the way to the 1930s. And ever since the irrigation project was built it’s been a bone of contention. It’s been one thing after another. Our tribe has had to take legal action against them. They’ve wanted to do irresponsible things like dry up streams and do some just real bone-head things, that you don’t even have to be a scientist or a biologist to think ‘Wow, that’s stupid to do.’”

Swaney’s protest and impromptu debate happened outside the same election that saw Tim Orr win the Mission district, replacing his former friend, lifelong neighbor and water compact supporter Jerry Johnson.

Johnson, who is not a tribal member, said the compact, while not perfect, was better than the alternative of costly litigation with little being accomplished. Orr’s position on the water compact ended his relationship with Johnson. The Johnson family has lived next to the Orr’s since the early 1900s, and the two men grew up together.

Enlarge

Orr was unhappy with the changes suggested in the 2013 draft of the compact so he decided to confront Johnson directly and drove to his neighbor’s house.

“I said ‘Jerry don’t do this, don’t sign this,’” Orr said. “I said ‘You don’t understand, you’re taking away our stock water, our duty water and non-quota water.’ It’s taking that right away from us and giving it to the tribe.”

This was the last time that the two neighbors talked.

Now, a yellow “For Sale” sign sits in front of Johnson’s 80 acres. Johnson, 58, and his wife plan to leave the area for retirement and to get away from the whispers.

“I found out who my friends were and I found out who weren’t,” Johnson said. “And the ones who aren’t my friends, I don’t say a word to them or anything today.”

Johnson said although the compact isn’t perfect, he wanted it to pass so that the crumbling irrigation system on the reservation could be fixed.

SIX DAYS after the 2015 draft of the compact passed, the Flathead Joint Board of Control filed suit against the Montana State Legislature.

They wanted to block Gov. Steve Bullock from signing the bill, and said the compact did not get a two-thirds approval in the House or Senate and that makes passing it out of the legislature unconstitutional. Bullock ignored their protests and signed the bill, and now the compact will have to make it through the federal government, a process that could take years or even decades, before it can be considered law.

Swaney said that the festering contention over the compact is unlikely to change in the meantime.

“You involve elected officials and politicians and everything gets crazy,” Swaney said. “I don’t see any real diminishing of some of these attitudes we’ve already seen rise up.”

Meanwhile, for Jerry Laskody and other irrigators, said the accusations that they are racist is just a way to distract from the real issue: Who owns the water?

“I don’t have any animosity toward the typical tribal person,” Laskody said. “First of all they’re not irrigators so they’re not really involved in this thing. This is really a deal by their government to obtain control of all this water … It doesn’t affect their daily life; they’re not concerned about it.”

Swaney said she and plenty other tribal members care about the water, but they care about more than just the irrigators and farmers on the reservation. She said there’s a need to preserve water in the streams and creeks.

“Is there going to be enough water that it will be running down the streams?” she said. “And the forests won’t dry up and there’s enough for wildlife and fish. I don’t think, ‘Is there enough water for farming?’”

Many tribal proponents of the compact feel that the tribe has compromised on the compact enough already, and it’s long past time to shore up and protect their water rights. Swaney said the tribe has proven itself capable of managing and maintaining the water supply.

“In my perfect world, as long as the tribe is allowed to protect ourselves and our homeland, we reserve ourselves that water,” Swaney said. “And anything left over to share; well we’d gladly share that. But it doesn’t mean that everybody on the reservation, tribal or not, gets to do everything they want. We’re trying to meet the greatest needs for the greatest number of people.”

The compact faces an uncertain future in the U.S. Congress. While the Confederated Salish-Kootenai Tribes waits to receive what they say is rightfully theirs, and the Joint Board of Control and their allies wait in hopes that it fails, the people on the reservation must keep asking: Who owns the water?

For past Native News editions visit the archive here.