Story by Andy Bixler, photos by Ken Rand

Earning a college degree in the medicine field is hard enough. Consider the finances, the rigorous course curriculum, long hours. So, earning that degree with a 4.0 grade point average makes it impressive.

And still, a mother of three, who admittedly lacks the confidence to help her children with homework, and a high school drop out to boot, the odds were stacked high against Michelle Lonebear.

But on May 7, Lonebear, a mid-30s mother with a G.E.D. and member of the Assiniboine tribe, graduated from the Aaniiih Nakoda College. It was the first time she ever graduated. And she had done so with high praise.

“She has become such an impressive young woman,” said Carole Falcon-Chandler, the tribal college president. “She gets scholarships, she represents her school well, but it’s the little things. I sometimes see her walking around campus, picking up trash.”

Because of programs that specialize in recruiting people of color, in particular women of color, this likely won’t be Lonebear’s last graduation.

Lonebear’s experiences have taught her a lot about the importance of education. But if not for programs like the Allied Health program at Aaniiih Nakoda College, created to address the deep need for students like her in the STEM field—Science, Technology, Education and Mathematics—she might not have stood a chance.

Ten years ago, a dropout from the reservation with three kids going into a highly technical field like nursing was unheard of. Today, at Aaniiih Nakoda, it’s commonplace.

All across the Fort Belknap reservation, more women are enrolling in STEM classes, in hopes that they can earn nursing degrees and try to fix a healthcare system they consider to be failing.

Globally, educational institutions from middle schools on up emphasize the STEM fields. But, particularly in minority populations, the complex and demanding subject areas tend to deter more students than it attracts.

At Aaniiih Nakoda, student enthusiasm for STEM shows in the success of the Allied Health program, which awards a two-year associate degree. Some think the popularity is in response to the local job market. Others see it as a natural extension of a caretaker role Native American women see within themselves.

Of course, it wasn’t an easy road.

Lonebear’s student days started early, as she and her husband, Mitch Healy, worked together to get their three kids up for school.

Lonebear, 34, then drove from her house on Rodeo Drive, down the hill and past the Smokehouse Grill and tribal headquarters, to the Aaniiih Nakoda College.

It’s there she spent most days, studying. She took courses in anatomy and chemistry, biology and Native American studies, all while maintaining a home, and all while maintaining a perfect 4.0 GPA.

She’s a model student in class, her teachers said. Attentive and inquisitive, she volunteered for everything.

But Lonebear wasn’t always an ideal college student. She bounced around from school to school growing up, including a stint at a boarding school, before dropping out.

Enlarge

“I wasn’t a good student, I was a raise Cain,” she said. “Until I got pregnant, then I woke up and started doing good in school but it got harder with my son and no babysitter, so I just dropped it.”

After being a stay-at-home mom, Lonebear decided she wanted a better job, so she got her GED in 2013. As soon as she passed her GED test, she enrolled in college.

“That was the scariest moment of my life,” she said.

Another aspect is the recruitment of minority women, like Lonebear, into STEM programs. Schools like the University of Montana have administrators and programs whose sole purpose is to recruit and assist minority women studying STEM-related fields. Aaniiih Nakoda College doesn’t have those resources, but the field is popular enough that targeted recruitment isn’t necessary.

Stories of poor care, inadequate attention and people dying during the long wait to access proper care at the federally run Indian Health Services clinic prompt locals to enter health care fields.

Women especially take it upon themselves to try and make things better, which in itself is a rarity. The Economics and Statistics Administration says women fill almost half of the jobs in the U.S., but after graduating, women take only 24 percent of the STEM jobs, even with 50 percent of the graduation rate.

These jobs, like engineering and research science, are often more stable and higher paying. The same report says women who have jobs in STEM fields earn 20 percent more over their lifetime than if they had worked elsewhere.

The Aaniiih Nakoda College president’s office is cozy, decorated with Native American artwork amassed over 70-plus years of collecting. A deerskin drum painted with a red turtle in the center hangs above her framed doctorate degree from Montana State University, while a painting of a young Native American mother and her baby keeps watch over photos of her family on the other wall.

Carole Falcon-Chandler has been at the college since 1992, back when it was called Fort Belknap College, and has seen its Allied Health program go from an afterthought to the main selling point on campus. It’s from this office that the program has become what it is today.

Years ago, the environmental science program reigned supreme and attracted mostly men. That began to change a few years ago. Now, the Allied Health program is the largest on campus and it’s filled mostly by women.

Enlarge

Of the approximately 40 students enrolled in Allied Health, only three are men. Women in the program make up over a quarter of all 157 students at the college.

Falcon-Chandler said as president, it’s her job to oversee every part of the school, but she holds a specific pride for the program’s success.

“Because of the type of people that we had involved, it’s so important to us,” she said. “It’s been the leading program to us, and we just continue to keep building that.”

For Falcon-Chandler, the goal is to keep building, and her school has plans to do exactly that. On April 16, a delegation from the college presented a feasibility study to the Montana State Board of Nursing.

The school commissioned the study as the first step towards getting an accredited registered nursing program at the school. Currently, students who get their two-year degree from Aaniiih Nakoda College must go off-reservation to a four-year program to finish their nursing degree.

Enlarge

But this proposal, should it succeed, would allow students to stay in Fort Belknap, eliminating the need to either drive 80-plus-miles round trip each day to Havre, or move across the state to Bozeman or Missoula.

The building where the proposed four-year nursing program would go is one of the nicest and newest on campus. It sits at the far end and stands out for two reasons: At two stories it’s by far the largest building on campus, and the artwork on the front.

The building is currently home to the school’s welding program, another popular curriculum at the tribal college. Shortly after it was built, one of the instructors thought the front looked bare, so he designed and cut a statue of a bison skull.

Inside, classrooms, offices and the welding shop take up most of the room. The addition of more nursing classes would make it even more cramped.

Beds for imaginary patients, stations for learning how to administer IVs and offices for new faculty are all needed for accreditation by the board of nursing, according to the proposal.

All of that would be expensive, although there are no exact estimates of the cost – the stages of planning are still too early to work up any accurate numbers.

What the college does know is how badly the program is needed.

The college’s proposal says while 6.5 percent of Montanans are Native American, only 2.5 percent of registered nurses are Native American, which “diminishes the overall quality and diversity of care across the state,” according to the proposal.

The problem comes into greater focus in communities on and around this rural reservation. The proposal found that, at any given time, the Indian Health Services clinic in nearby Havre operates with a 25 percent vacancy for nursing staff.

That provides double the incentive for students – a personal reason to get into nursing, and a nearly guaranteed job upon graduation.

“Most of them have strong family ties, and these women that will be in the nursing program, we’re really hoping that they can come back and work in the area,” Falcon-Chandler said. “A lot of them have strong ties to their home.”

Lonebear doesn’t help her kids do their homework. That’s a job for their dad Mitch, a water scientist who works for the tribe and has a master’s degree. It’s not that she isn’t smart enough. What Lonebear lacks, still, is confidence. Education wasn’t a big deal in her home growing up.

“I’d like to think I have the confidence,” she said. “But I’m still working on it.”

Lonebear isn’t yet a vocal leader. She’s naturally shy, and looks away a lot when she talks, her shoulders hunched away from strangers.

Enlarge

Instead, she leads by example.

“She would say, ‘Oh, there’s a group that wants to fundraise, I can help with that, I can jump in there and do that,’ she’s always right there in our activities that way,” said Erica McKeon-Hanson, a professor at the tribal college.

Lonebear said she thought about becoming a doctor, instead of a nurse, which she thinks would be boring. But she, like many, see that goal as out of reach, not because medical school is too hard, but because it would take too long.

Lonebear doesn’t want to uproot her family and go to Salt Lake City or Seattle to attend medical school. She wants to start making a difference on the reservation as soon as she can. She’s 34 now, and after getting her bachelors degree, she would spend another four to five years in medical school, accumulating thousands of dollars in debt.

“It’s like, too long,” she said. “There are people to help and things to do right now.”

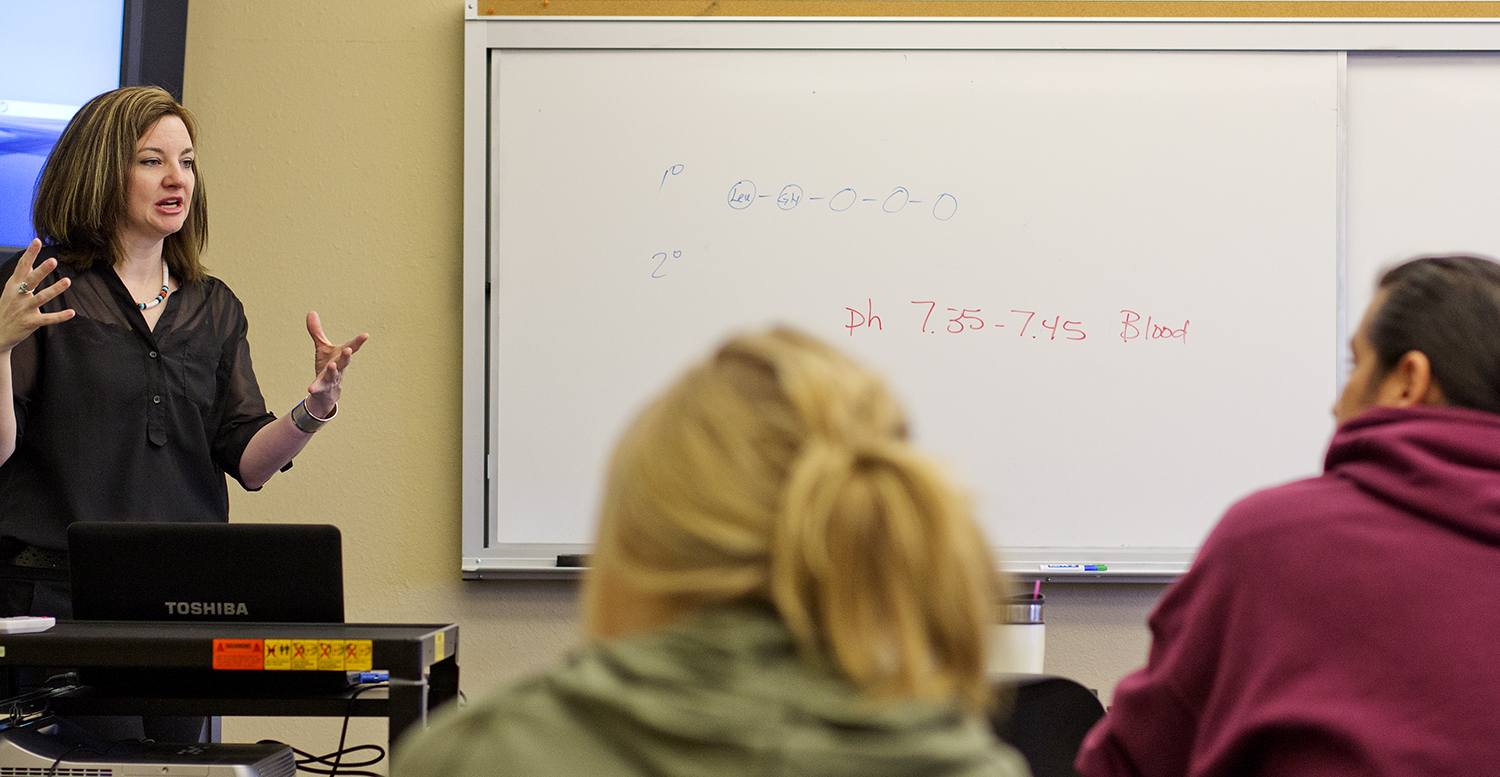

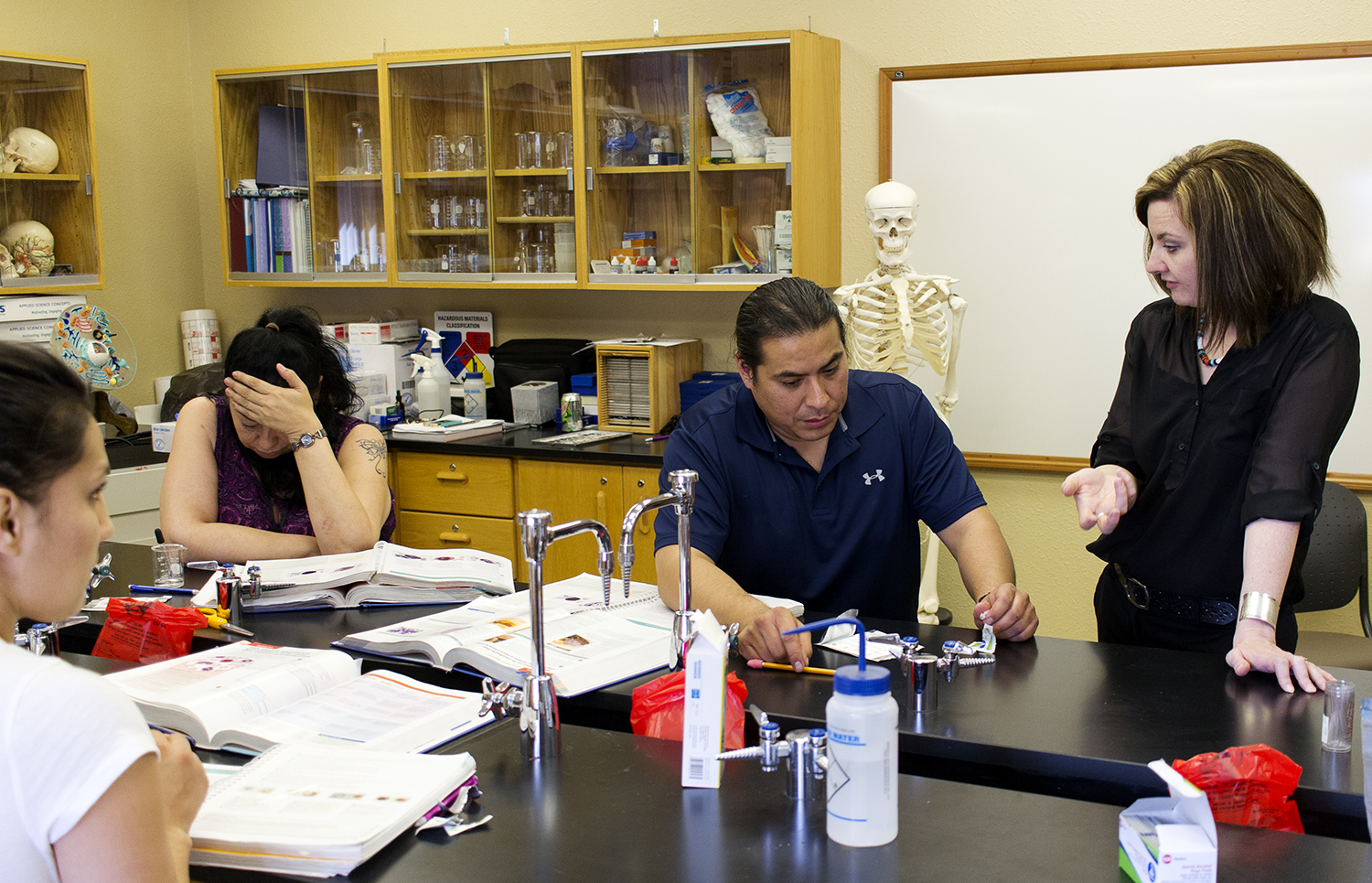

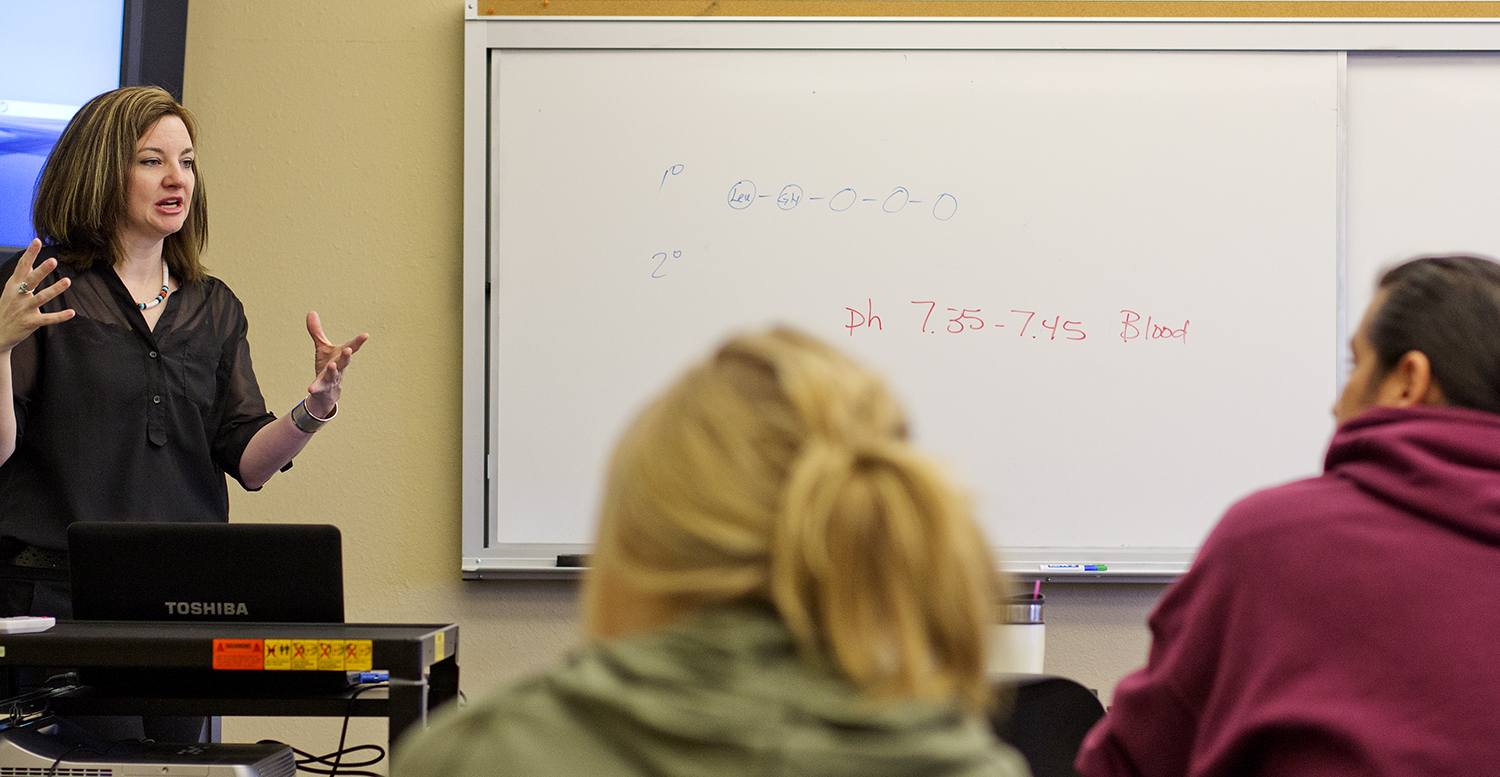

McKeon-Hanson stood in front of her eight students in the Little River Learning Lodge on campus. Seven in the room were women, two were men.

The walls were bare, save for a poster of the periodic table of elements and a clock with no numbers that read “I ‘heart’ Anatomy,” with an anatomical drawing of a heart where the word should be.

Enlarge

The students sat facing her at long tables with two empty chairs between each student, save for a married couple in the class who sat side-by-side.

McKeon-Hanson, who was just getting over the flu, was lecturing about blood types. There are three main categories, she said.

“Can anybody name them?” she asked in a still-raspy voice.

“A-positive?” one of the two men guessed.

“Well, sort of,” she said.

Having women outnumber men in STEM classes is a common occurrence at this tribal college, but not many other places, and especially not Native American women.

According to the National Girls Collaborative Project, while women earn half of all STEM degrees, only 11 percent are earned by minority women. On the Aaniiih Nakoda campus, that number is closer to 50 percent.

Bryar Flansburg is the teaching assistant for McKeon-Hanson’s anatomy class and came through the Allied Health program herself after graduating from nearby Havre High School. Everyone in her family is involved in science or technology in one way or another.

Flansburg, her sisters and mom all have biology degrees, and her dad, who worked in the IT department at the college, has a master’s degree in computer information.

Enlarge

Her dad led the family in graduating first from Aaniiih Nakoda, followed by Flansburg and her sisters, and finally her mom, who earned a diploma last year.

“We’re all interested in medicine, and pursuing that,” she said.

Her office is in a small lab in the Little River Learning Lodge – although calling it an office is kind of like calling a Ford Pinto a Ferrari.

It’s really just a chair pulled up to a computer, impossibly wedged between piles of paper and boxes of pipettes. From there she writes lesson plans and applies for grants while preparing for her own future, which will begin this summer when Flansburg enrolls in Montana State’s nursing program.

After graduation she wants to come back to the reservation to work as a nurse.

Flansburg says she wants to come back because she sees her home as “underserved,” and thinks she can help improve the quality of healthcare provided on the reservation.

She says a large part of the problem stems from outsiders, who blow through the reservation on the Hi-Line as though carried on the wind, not understating tribal culture.

Flansburg knows how important good health care can be.

She gets emotional when talking about her family’s medical issues. Her sister recently lost a baby. Her dad had an aneurysm and nearly died. Her mom has been diagnosed with breast cancer.

“That’s been the motivator for me to go back to school,” she said. “That’s why I want to do nursing.”

The lack of Native American health providers can lead to problems. Many of the providers on and around the reservation come from somewhere else, and don’t understand the complex nature of health care on a reservation.

Flansberg says non-Native Americans have trouble trusting or communicating with Native American patients, which can lead to disconnects that only make health issues worse.

“It’s their whole approach, when they’re talking with their provider about what’s wrong with them,” she said. “Rather than being like ‘oh, you’re supposed to do this,’ and they don’t understand how hard it was just for them to get there.”

The college does offer cultural training as part of its curriculum, McKeon-Hanson said, which is meant to help bridge those gaps.

But the students at Aaniiih Nakoda College don’t need to learn it. Most, like Flansberg, have already lived it.

“Most students have an experience in their life where they’ve gone for health care, and a medical provider doesn’t understand their life and their approach to holistic health and wellbeing,” McKeon-Hanson said. “They often feel judgment, and not understanding, that when you’re treating an individual in the American Indian community, you’re treating the whole family.”

Lonebear’s living room is tiny, with two couches that face each other so family and guests can sit and talk. The wall is covered in photos and trophies.

Her kids are already there when she gets back from school. They’re all old enough to get themselves around the small town without mom. That’s one of the reasons Lonebear waited so long to go back to school, she wanted to make sure her kids were old enough to handle her being gone all day.

Lonebear’s decision to go back was uncommon, and one that has potential to pay great dividends. According to estimates from the 2010 Census, most jobs on Fort Belknap for women are in two main categories: sales and office jobs, or business and science jobs.

But as Lonebear has gone through the program, she’s grown. Falcon-Chandler says she is becoming more vocal and an even greater leader on campus as she’s found her voice.

Lonebear plans on going to MSU-Northern next fall to study preventative health care. Lonebear says she’s less interested in helping those who are already sick and more interested in stopping them from getting sick in the first place.

“I want to stop the problem before it starts,” she said. “There are plenty of people who try and make you better, but not many people on the reservation realize that a different lifestyle makes life better. I understand people, I know what they need, and they can’t get that from others. They’re my family, and I have to help them.”

For past Native News editions visit the archive here.