| Summer 2004 |

Sovereignty

|

|

|

Fort Peck Reservation A lost son, a loss of faith

story by Natalie Storey

But rumors are sometimes worth listening to, Starr says, especially if there is a whisper of truth in them. So when people tell her that her son was beaten to death after what was possibly a jealous dispute between him and another man over his girlfriend, Starr is skeptical. But she doesn’t disregard the tip altogether. “They said they put his body in the water, but not in the river,” she says, reciting one of the more convincing tidbits of information she has heard. She says she’s heard this bit of information from a number of sources, including from a man she says has already confessed to aiding in the crime. Starr and her daughter, Janelle Red Dog, look along the banks because they think it is a likely place for the assailants to have dumped the body. They stare, squinting, out at the river. The wind whips their long black tresses into their faces. Their eyes are glassy from the wind, or maybe from emotion, and they say they feel like they have been looking alone for their lost loved one. The wind and leftover snow along the river are reminders of the harshness of seasons in Northern Montana. But the elements alone haven’t been enough to keep the Red Dogs from looking. The snow and wind, after all, aren’t nearly as harsh as their feelings of betrayal toward tribal police investigators and the tribal council. Because Red Dog disappeared on the reservation the case is under the jurisdiction of tribal law enforcement, rather than a law enforcement agency of the state. Red Dog’s family says tribal investigators have failed to adequately conduct searches and question potential witnesses connected to the disappearance. Starr calls the Fort Peck tribal investigators unprofessional and says she would rather the FBI, the Bureau of Indian Affairs or any other law enforcement agency was investigating the crime. It would be better that way, she says.

“These guys wouldn’t still have their jobs if they were off the reservation,” she alleges. Tribal police investigators say there are few verifiable clues to the disappearance of 27-year-old Bodean Red Dog, a man who often spent long stretches away from the reservation, working carnivals. And, in the days after the family reported his disappearance, heavy snowfall prohibited ground searches, they explain. But they also express other concerns. “The question is, ‘What are we searching for?’” asks Terry Boyd, lead criminal investigator for the tribal police. There are, he says, more questions, than answers in Red Dog’s disappearance. “Short from searching the entire continental United States, there isn’t a lot we can do.” The Red Dog family is convinced their son and brother was murdered and say someone should be looking for his body and evidence of a crime. It’s a task they’ve taken on themselves, with the aid of tribal Fish and Game officers. “If that was one of your relatives out there you wouldn’t care if it snowed, you’d be out there digging with your hands,” Starr says. On a frigid, windy day in March, months after his disappearance, searchers combed the fields and river banks, but turned up nothing. Fish and Game officials helped the Red Dogs with this search, but they have also been conducting other searches for Red Dog since his disappearance. Head warden Bruce Bauer says he decided to have his officers look for Red Dog when no other agency was searching. “I go out there out of compassion for the family,” Bauer says. “I started doing it because no one was going to do anything because of the snow.” Game wardens have searched on and off all winter, mostly within a 10-mile radius around a place called Dago Bend, a stretch of road that twists and turns near the Poplar River. It’s near many of the popular party and cruising spots, Bauer says. Besides that, he adds, they’d heard the same rumors around town that had reached Rhea Starr. Bauer says tribal investigators have not helped his outfit with the searches, but he also notes that Fish and Game is better equipped to conduct searches during the winter months, since wardens have snowmobiles and other equipment. The Red Dog family believes criminal investigators made a vital mistake in the early stages of the investigation when one family member, Starr’s cousin Stephen Gray Hawk, found a patch of ground matted with blood. He was hunting near Dago Bend area just before Christmas. At first he thought he had seen deer blood, but when former police officer Gray Hawk investigated further, he became convinced what he was looking at was the scene of a crime.

“The way it looked — it just didn’t look right,” he says. “I see deer blood a lot and it’s just, it’s just different.” Gray Hawk and other relatives immediately reported what he had seen to tribal police. But the family says the investigators failed to check out the spot. Boyd says heavy snowfall prohibited searches during much of the winter. The first big snow came in late October, when about 8 inches fell. By Christmas about 2 feet of snow was on the ground. Gray Hawk says he’s searched for the spot several times since he first came upon it in December, but a snowstorm soon covered it and he couldn’t locate it again. Starr says investigators could have checked out the spot as soon as Gray Hawk notified them, which was before the storm. Boyd says that criminal investigators had one helicopter search after Red Dog disappeared and have followed up a number of leads, all to no avail. In April, after repeated complaints from the Red Dog family, tribal police formed their own search party and began to look for Red Dog. But Bauer of the Fish and Game says they are just covering the same area Fish and Game has already combed. “It’s just a big waste of time and money for them to search the same places we have,” he says. “It’s just frustrating. They should start working with us.”

Under the federal major crimes act, the FBI and the tribal investigators have shared responsibility for investigating serious crimes such as murder on the reservation. But since cross-deputization took effect, tribal police have been investigating and solving more crimes on their own, Terry Boyd says. Fort Peck tribal police have one of the highest caseloads of violent crimes in the country, Boyd points out. Missing person cases are not covered in the major crimes act and thus are the sole responsibility of tribal investigators, at least until they become murder investigations. Boyd says tribal investigators do everything they can to investigate cases like Red Dog’s, but can’t ask the FBI for help until a body is found and investigators are sure a crime was committed. “It’s difficult for people to accept, but the reality is that until there is clear evidence a crime was committed there is not much we can do,” Boyd says.

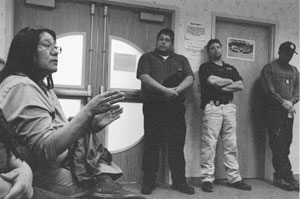

However, Dan Vierthaler, the FBI’s supervisor for Eastern Montana, says many murder investigations are opened by the bureau before law enforcement agencies locate a body. “If there is reason to believe a homicide has occurred, then there doesn’t necessarily have to be a body,” he says. Vierthaler says he cannot comment on the status of the Red Dog case, but says the FBI is aware of it and is interested. Rhea Starr says she doesn’t have to see her son’s body to believe there was foul play. Aside from the rumors around town, there is mother’s intuition. “Right away I got the feeling something had happened to him,” Starr says. “But they considered my son a missing person. I told them my son would never be gone this long without letting me know. Something had happened to him. I just had that feeling in my heart.” Boyd said it’s hard to know what happened to Red Dog. “This guy disappears in mid-December and has a habit of leaving and going on the carnival circuit,” he says. “He could be anywhere.” Red Dog wasn’t working for the carnivals at the time of his disappearance, his mother says. He was in between jobs, having quit the carnival circuit and his firefighting job. Violet Bruce, mother of Red Dog’s 7-year-old son, Cylise, says when his carnival work took him far from Montana, Red Dog was always good about calling his son. Cylise Red Dog is a bashful boy who strongly resembles his father. Bruce says he has the same pug nose and his nostrils flare when he gets angry, just like Bodean Red Dog’s did. Cylise hasn’t spoken to his father since November, but he’s not eager to talk about that. He hides his face behind his mother as she talks about how Red Dog always used to phone. “I keep wishing that they’ll find him,” Bruce says. “That’s the hard part … He misses his dad.” Bruce says Red Dog’s calls became less frequent when he began dating a white woman. The woman has since left the reservation, but while the two were dating they often had tiffs that grew from jealousy over her reportedly seeing other men, Bruce says. But friends and family say Bodean Red Dog was not much of a fighter. He had problems with drinking, they acknowledge, but say he was never a violent drunk. And, above all else, they say, he was a compassionate man. He’d give money to people down on their luck, even when he didn’t have much money, or luck, himself. Starr won’t rest until the tribal investigators she says messed up her son’s case are fired from their jobs. She and her sister have circulated a petition asking for their termination, and they’ve collected hundreds of signatures. On one windy afternoon Starr and Kara Red Dog, Bodean Red Dog’s aunt, file into the tribal council chambers with about 25 other family members and friends to attend a meeting of the law and justice committee, the tribal body that oversees the police force. This is the third time Starr and her sister have been here to complain about the criminal investigators.

Starr calls out their names slowly: “Terry Boyd … Ken Trottier … Tom Atkinson.” Starr has also written letters to Gov. Judy Martz and the head of the BIA in Albuquerque, N.M., requesting an independent investigation into her son’s disappearance. “They’ve outlived their usefulness here,” she says. “They have no rapport with the local community—nobody will talk to them.” Tommy Christian, who is chairman of the meeting, listens patiently to their complaints, although he’s heard them all before. He says his job is to look out for the criminal investigators as well as the Red Dogs’ interests. Tribal chairman John Morales wants the investigators to be present so they can hear the complaints. But the committee argues back and forth about whether it’s appropriate to drag the investigators away from work and into the meeting. Finally, they decide it is time for the investigators to address the assembled crowd. Within the hour the men arrive and stand in the corner, arms crossed, gazing toward the floor. Starr is near her breaking point. And her sister is angry. “We want to know why people weren’t interviewed,” Kara Red Dog demands. “We have a limited amount of resources right now,” Boyd answers. “It’s based on our judgment and what we deem to be appropriate to investigate.” Boyd will not answer many of the spectators’ questions. He says he is prohibited by law from talking about an open investigation. He repeatedly requests the council call an executive session so he can talk with the council and the Red Dogs in private. The Red Dogs say they have been treated rudely by the investigators. Kara Red Dog says her sister waits by the phone all day expecting a call from investigators, a call she says they don’t have the “decency” to make. Morales says his office will begin an inquiry into the conduct of the criminal investigators, but the Red Dogs want them fired today. They say they’ve been waiting long enough for the council’s law and justice committee to take action. Rhea Starr says her tribal government has let her down and the tribal investigators have betrayed her. Boyd does not defend himself in the public meeting. Later he calls the people who criticize him “idiots” and says, “I don’t really care how they feel because a lot of it is bullshit at this point.” Boyd thinks Red Dog’s family and friends have spoken out against him at the meeting to seek revenge for investigating crimes in which their relatives were suspects. He says they cry “alligator” tears in front of the cameras and the tribal council. “They aren’t there because they give a rip about Rhea,” he says. “They are there for vengeance.”

Back at the meeting, the tribal council calls an executive session. Boyd says there has been a development in the Red Dog case that he can’t share in public. He asks Starr to stay for the closed session to hear what he has to say. But tears are already streaming down Starr’s face and she won’t stay. She stands up to leave but addresses the committee one last time before she goes. “I just want all of you to know that I feel failed,” she says as she turns and walks out the door, not waiting to hear what investigators will say about her son. Outside, she vows to never give up her fight. She’ll fight forever to find her son. And she’ll fight as well to change a system that she says let her down. |

Last

updated

9/18/04 1:42 PM

Table of Contents | About Us | Feedback | Links

Two women stand along

the ice-crusted bank of the Poplar River straining their eyes

against the sun and struggling to breathe

in the spring wind. It’s been more than three months since

they last saw their son and brother, Bodean Red Dog, who disappeared

last December.

Two women stand along

the ice-crusted bank of the Poplar River straining their eyes

against the sun and struggling to breathe

in the spring wind. It’s been more than three months since

they last saw their son and brother, Bodean Red Dog, who disappeared

last December.