Sammy

Ray Dupree stopped giving herself insulin shots at school after

a classmate accused her of shooting up crank.

Like two others in her family, 14-year-old Sammy is an insulin-dependent

diabetic and must inject herself with insulin twice a day. That

means giving herself a shot between classes at the junior high

school she attends in Poplar on the Fort Peck Reservation in

northeastern Montana.

Sammy has permission from teachers to give herself insulin in

the relative privacy of a bathroom stall, but in Poplar, which

has a severe problem with methamphetamine use, hypodermic needles

have a bad connotation.

So when Sammy’s classmate saw her capping a needle as

she walked out of a stall, the girl assumed the worst. Sammy

is sensitive about her condition to begin with, and after being

falsely accused, she’d had enough.

"Ever since then," Sammy says, "I never did it

at school anymore. I just wait until I get home."

Sammy and her family are struggling to live with Type I diabetes,

a form of the disease uncommon in American Indians. Type II,

which usually develops first in adulthood, is epidemic among

Indians, affecting more than 12 percent, twice the rate of occurrence

in the white population. The incidence at Fort Peck mirrors

the national rate at 12 percent.

Sammy, a sister and her father all live with this life-threatening

disease. It’s been both a physical and emotional struggle,

made even more difficult when the girls’ mother contracted

cancer, which is the second leading cause of death in American

Indian women.

American Indian families are hard hit by disease. Indians in

Montana have a life expectancy of 10 years less than white Americans

nationwide. And the federal government spends half as much per

tribal member as it does for health programs for other Americans.

However, in many Indian families, like the Duprees, while health

concerns are pressing, the ways in which they cope are complicated.

Sammy says she hates living with her diabetes, hates the way

it makes her different from her classmates, and hates talking

about it.

The youngest of five sisters, she shares the illness with her

19-year-old sister Rosebud and her 51-year-old father Raymond

Dupree. All three have Type I diabetes, which means their bodies

produce no insulin.

Insulin is a protein made by the pancreas that allows sugar

from the bloodstream to be transferred to the cells for use

as energy. For Type I diabetics, in order to keep blood sugar

from getting too high—a condition that can lead to a coma

and eventually death if not treated—insulin must be injected

into the bloodstream.

Type I used to be called juvenile-onset diabetes since it usually

appears during adolescence. Rosebud developed diabetes when

she was 6. Her mother, Gail Charbonneau, remembers Rosebud asking

one night for glass after glass of tea with sugar. Gail didn’t

know at the time that excessive thirst, along with frequent

urination, are warning signs of diabetes.

Yet while she didn’t recognize the symptoms of diabetes,

Gail certainly knew the treatment, having learned to give insulin

shots to her grandmother when she was 14, as well as living

with a diabetic husband.

When Rosebud first became sick, Gail carried her into the emergency

room at the Poplar hospital at 2 a.m., but the clerk at the

front desk didn’t understand the seriousness of her condition

and told Gail to come back at 8 a.m. Realizing that her child

was in danger, Gail ignored the clerk and stormed past her to

the doctor on duty. The physician took one look at Rosebud and

tested her blood sugar. Normal blood sugar content is from 70

to 120 milligrams per deciliter. Rosebud’s level was 907.

It wasn’t long before she lapsed into a coma and had to

be flown to Billings for treatment. She survived, but from that

point on, she and her family were saddled with the lifelong

responsibility of caring for a diabetic.

Diabetes can kill, but it can also be controlled by insulin,

diet and exercise. However, what Gail Charbonneau faced five

years ago was not so easily conquered.

Gail was diagnosed with breast cancer and because of the severity

of her condition she needed experimental treatment the Indian

Health Service would not cover.

Doctors warned that Gail would die without the stem-cell treatment,

but the $80,000 price was far beyond the family’s reach.

They searched for programs or grants that might provide the

money Gail would need to have a shot at survival.

Even as she grew sicker, Gail tried everything to earn the money.

One day as she dug echinacea roots to sell, her sister came

running to tell her that her mother, Myrna Charbonneau, had

found a way.

After hearing pleadings from Myrna, the family says a doctor

at the Indian Health Service in Washington, D.C., was able to

redirect money set aside in a disaster fund to pay for Gail’s

treatment.

"I was just happy, because this thing was hanging over

my head and if I didn’t have it, you know, I was gonna

die and what’d happen to my girls?" Gail says. "That

was the best thing I ever heard."

Within 24 hours, Gail and Myrna were on their way to Billings

for the treatment Gail needed. But her stay would be long and

the treatment difficult so Gail sent her daughters to live with

their eldest sister in California, splitting up the family.

Myrna, a nurse, knew Gail would need her by her side, so she

went along though it meant giving up her job.

Again, money seemed a barrier. Faced with no income and setting

up a second household 300 miles from home, again Myrna found

a way. She sold her mineral rights on land that she owned at

Fort Peck, land that had been deeded to her family during the

allotment of the reservation.

Gail and Myrna moved to Billings to begin the treatment. But

paperwork from the Indian Health Service didn’t arrive

so they spent the first month waiting.

At Christmas, Gail’s daughters came to visit, but her

doctor warned that she shouldn’t leave the hospital.

She remembers his words exactly: "He said, ‘You know,

you’re a walking dead woman,’ because I had no immune

system."

But Gail went anyway and while she was with them, she sneezed,

and her nose started bleeding and wouldn’t stop. Her family

rushed her back to the hospital and she was given pills to help

her blood clot.

Even with all that, Gail says the most difficult part of her

treatment, which lasted a year, was being away from her family.

Eager to get back to Poplar, she was relieved to hear that some

final stages of her treatment could be completed on the reservation.

So she moved home, then found it wasn’t so. They returned

to Billings and completed the regimen and then went back again

to Poplar where she could resume taking care of her children.

After spending her life caring for others, cancer had forced

Gail to care for herself. But she’s now been cancer-free

for three years and has gone back worrying about the other potentially

deadly disease that affects her family.

Just as Gail now understands intimately the physical havoc cancer

can wreak, she knew already the damage diabetes can do. She

and her sisters watched their grandmother suffer from the disease.

Gail’s sister Jeannette Charbonneau lived with her grandmother

for a time and remembers the way diabetes slowly ate away at

her body.

"They cut first her foot off, then this part off,"

Jeannette says as she points to her calf. "Then she got

this other one (foot) cut off. And she lost her sight, and after

she lost her sight she just decided to kind of give up. She

wouldn’t eat. After two weeks, she starved. She said she

had a long life. She was 89."

Diabetes is a full-time disease that cannot be ignored.

Pauline Boxer works for Fort Peck Diabetes Outreach and after

having watched her own mother die from the disease, and then

getting it herself, she has devoted her life to educating other

Indians how to live with it. She says she knew the disease only

as a name growing up, but never thought about its implications

or that she might someday get it.

"When I found out I was a diabetic, it about blew my mind,"

she says. "I said ‘I don’t want to be a diabetic,’

because I seen what my mother went through. My mother was a

Type II diabetic; she ended up on dialysis, she ended up getting

her fingers chopped off, she went blind, she lost her hearing,

and then she just had a heart attack. I don’t want to

see anybody go through that."

Pauline knows many people are in denial about diabetes but she

knows too well the consequences.

"I look around and I see people younger than I am that

are completely blind because they don’t want to do anything

with their diabetes," Pauline says. "They

don’t want to take any kind of education. They don’t

want to commit to the program and listen to the nutritionist.

They don’t want to come in and see the foot doctor. They

don’t want to get their eyes checked. They think they

have diabetes and nothing else is gonna happen to them. But

that’s not true. People are losing their limbs because

of diabetes, people are going blind because of diabetes. People

are having heart attacks, people are ending up on dialysis.

It’s a sad thing to see most of our Indian people with

diabetes."

Although the Dupree family deals with the less common Type I

diabetes, the health risks are still formidable.

Raymond, 51, was told five years ago he would be blind within

a year, but has managed to keep his vision so far.

Rosebud, now 19, has gone into a high-blood-sugar-induced coma

more times than Gail cares to count and has already been referred

for dialysis treatment, though she has managed to avoid it by

taking better care of herself. If diabetics let their blood

sugar fluctuate too much, it can eventually lead to kidney failure.

Dialysis cleans a person’s blood of toxins when their

kidneys begin to fail.

Rosebud sounds resigned to the probable progression of her disease

and eventual dialysis.

"If I need it, I’ll probably just go ahead and do

it," Rosebud says, but also says she accepts what might

eventually happen.

"I’m just not afraid of dying," she says.

Rosebud is also on a list to receive a pancreas transplant.

The pancreas produces insulin and is usually transplanted in

concert with a kidney. But because of the powerful immunosuppressant

drugs a person must take to keep the body from attacking the

foreign organ, 15 percent of patients who receive a new pancreas

die within five years.

Jeannette says Rosebud’s outlook changed after she came

out of one of her more recent comas and that since then she

has been taking better care of herself.

"Rosebud came out of that coma different," Jeannette

says. "Her whole perspective was more positive."

But Gail and her sister Jeannette are pleased with what they

see as progress on some fronts, but still worry about Rosebud,

who has been living by herself for four months.

"She’s got her phone shut off now," Gail says.

"God, if somebody doesn’t hear her, you know? What

if one of these days we go over there, she’s in a coma?

I just want to move her back to the house; I’m not comfortable."

And even if Rosebud is better, Gail thinks she has a way to

go before she is doing all she must to get healthy.

"She won’t even go over there (to the hospital) by

herself," Gail says. "She’s still like a child.

She’ll come over to the house and sit there, ‘Mom,

I’m sick.’ I say ‘You want to go the hospital?’

She goes, ‘Yeah.’ She won’t go over there

by herself, so she waits around for me to take her. She gets

dehydrated. She was wearing a size 9 pant, and she’s down

to like a 5 now. It just takes a toll on her. She’s still

sickly right now."

Both Rosebud and Sammy say Raymond was a poor role model with

his denial of his disease.

"Probably where I learned to be ashamed of my diabetes

is from my dad," Sammy says. "He don’t talk

about it at all."

Gail agrees.

"It probably comes from their dad," she says. "You

know when I first met him, I heard he was diabetic, but I’d

never really seen any of his medicine until 8 months later when

he got sick. He’s done insulin shots since he was 15.

I mean he kept it from me, he wouldn’t even tell me he

was diabetic. I knew he was. He’s real private. He won’t

tell anybody and if he got sick, he just got sick."

Raymond declined to speak about his illness for this story.

Gail says after Raymond developed diabetes when he was 15 years

old, he would have to walk to the government health clinic every

day to get his insulin shot. He has hated going to clinics ever

since.

"He still to this day won’t go up and get his own

medicine," Gail says.

Gail says Raymond’s fear of getting help and his denial

of the disease have had their effect on Rosebud and Sammy. She

says because Raymond doesn’t always eat enough, he frequently

goes into seizures from low blood sugar and has to be held down

to have Kool-Aid poured in his mouth.

"It scars the girls the most seeing their dad like that,"

Gail says. "They never want to be like that."

Rosebud says if she has children, she hopes things will be different,

but isn’t sure they will be.

"I wouldn’t want my kids to go through the same things

I went through," she says. "I’d probably try

to talk to them, but I don’t know until that time comes."

Sammy still struggles to come to terms with her illness.

"I don’t like it at all," Sammy says. "I

hate living with it. It really sucks."

And Gail, dealing with two daughters and a husband with diabetes,

just tries to take it as it comes.

"You have to deal with it one day at a time," Gail

says. "Living by the needle isn’t easy."

back

to top...

|

|

|

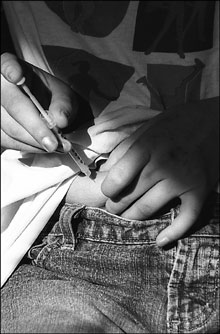

| Rosebud

Dupree injects her belly with one of the two daily doses

of insulin that her body requires to function. When Rosebud

was first diagnosed at the tender age of 6, her older

sisters had to learn how to give the injection. Now, says

Rosebud, she's even taught some of her close friends how

to give the shot. |

|

| The

Dupree sisters, from left, Raylene, Sammi Ray, Shyann,

Billie Ray and Rosebud gather for a photo opportunity

in the youngest, Sammi Ray's room. The girls got the giggles

after Raylene squeezed on to the side of the bed, breaking

the springs and collapsing the backside of Sammi's new

bed. Despite the suprise, the five seemed happy just to

be together. |

|

|

Family

members, from left, Billie Ray, Brenden, Rosebud, Sammi

Ray and Brady, gather around their mother's table for

dinner. Even though Sammi Ray is the only child still

living with Gail Charboneau, Gail's home is always filled

with family. Billy Ray says it's a place where the Dupree

children can get together to visit and resolve problems

they have. |

|

|

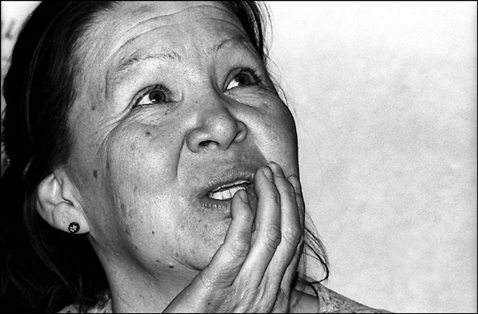

Gail

Charboneau peers out of the tiny Tribal Express office

where she and her daughter Rosebud work. Gail is the manager

of three gas stations along Montana's Hi-line. Her sister

Jeanette says Gail continued to work even through her

battle with cancer and often works double shifts. Gail

says she just appreciates the chance to keep a close eye

on her daughter. |

|

| Determined,

strong-willed and energ-etic, Billie Ray Dupree works

out daily to care for her body and keep it fit, in light

of her genetic disposition toward developing diabetes. |

|