|

|

||

|

Firefighting

fuels Story by Jennifer

Perez The day he turned 11, Richard Campbell was wrestling half way across the world from his home on the Fort Peck Reservation in northeastern Montana. The highlight of his wrestling career came in 1995 when he traveled to Tokyo, Japan, and won an international competition in his weight class.

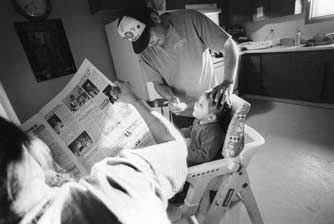

Richard has competed across the state and the country, as well as with the world wrestling team Stars & Stripes, his team when he won the tournament in Japan. Six years later his brother Ely, 11, is grappling in meets across the state and has dreams of the Olympics. The boys’ father, Harvey Campbell, is their coach and foremost supporter. Campbell has coached wrestling for eight years after a long mat career of his own. “The proudest moment was when I heard Richard took first in the tournament,” he says of his son’s victory in Japan. Harvey and Monica Campbell have 10 children between them, the youngest age 2 and the oldest 25. Football, basketball, baseball, track, wrestling, and cross-country are all Campbell family sports. It’s an expensive passion, but one the Campbells feel is well worth the cost. To afford the many trips his children take to compete at the top levels, Harvey Campbell relies on the income he makes as a forest firefighter. Campbell has other jobs in the off-season. He’s tended bar off and on for 28 years, beginning in 1973 at his father’s bar in Box Elder. On occasion he still works shifts in Wolf Point and Oswego over the winter months to make extra money. And, since 1994, he’s run a business installing insulation in Fort Peck-area homes. But last season Campbell earned $25,000 for his firefighting work, an important source of income for him and about 3,500 other Montana Indian firefighters. Many Montana fire crews come from the state’s seven Indian reservations, where unemployment rates can reach about 70 percent in the winter months. During last summer’s disastrous fire season, Montana Indian firefighters provided over a quarter of the crews called out for the large fires across the state. Fort Peck supplied 330 forest firefighters. The Blackfeet Reservation has the largest emergency fire program, last year generating about $5 million in earnings, while Fort Belknap came in second with about $3.5 million. Earnings at Fort Peck totaled $1.6 million. Nationwide, nearly 5,000 Indian firefighters were on the lines last summer. Though American Indians make up less than 1 percent of the U.S. population and 7 percent of the state’s, they account for 20 percent of the nation’s wildland firefighting force. The $13.5 million total wages earned by Montana Indian firefighters and support staffs last year play a significant role in reservation economics. The earnings go toward supplying basic needs for many families. “It is a very positive impact as far as moneymaking is concerned,” says Russell Mail, Bureau of Indian Affairs fire control officer for 11 years. “The fire program saves the economy when times are tough.”

For the Campbells it means being able to afford the extras, like those wrestling meets. “If it wasn’t for the firefighting money, my son Richard wouldn’t have been able to go to Texas, Michigan, Pennsylvania or Japan,” Campbell says. The major employer for years for the Assiniboine and Sioux living on the Fort Peck Reservation was the tribally operated A&S Tribal Industries, which at its peak had a payroll that supported 498 workers. A&S had large contracts with the Department of Defense and during Operation Desert Storm manufactured camouflage netting and medical chests. Today it employs only 40 to 50 people. “So now, people rely on fire money,” says Mail. Russell Davis, oversight director of the Montana Indian firefighter program, agrees, saying emergency firefighting money has a more direct economic impact because typically government funds go to tribal governments and not individuals. “That money turns over about three times in the local and surrounding economy,” he says. But because of its depressed economy, there are not a large number of private businesses on the reservation and those that do exist can’t usually compete with the prices or selection in larger communities off the reservation. For example, Poplar’s only clothing store, the Fort Peck Merc, went out of business six years ago when it couldn’t make sufficient profit to stay in operation. The Campbells say they shop on the reservation in Wolf Point for their children’s basic needs and, like so many reservation families, they travel to Williston N.D., to do the majority of their shopping. Williston is 50 miles from the eastern border of the 2.1 million-acre reservation. North Dakota exempts Montana residents from paying a sales tax in that state, so savings realized by shopping out of state aren’t eaten up by taxes. The fire money Campbell earns pays for the bills, clothes, shoes, toys, or whatever the Campbell family needs. Every year they “try to put some money away for winter to pay for our vehicle insurance and rent for the house,” Harvey Campbell says. In March, he still had savings from last season.

Randy Fire Moon has been a Fort Peck crew boss for the past decade and a crew representative for the past three years. Last year, Fire Moon worked at the fire hall in Poplar and went on five fires, earning $20,000. He uses his fire money savings, and mechanic and roofing income to supplement his family finances throughout the year. He and his wife, Candace, bought a house last March and are making improvements like a fence around the property and a new roof planned for this summer. With his fire money he says he buys whatever their four children need to keep busy, a trampoline, basketball court, and bikes among them. The Fire Moons make most of their purchases in Williston or Billings. The Campbells and Fire Moons are typical of reservation families who bank on firefighting income. The 2000 Census pegged Fort Peck’s total population at 10,321, the second highest of the reservations. The census shows an Indian population of 6,391, though tribal officials project an undercount of at least 1,000.

The Fort Peck tribal administration is working to bring jobs and money to the area and has gotten help in recent years from at least one federal program. The USDA Rural Development office designated the Fort Peck Reservation as an enterprise community. That status, granted in 1999 and held by only two Indian reservations—Fort Peck and South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation—entitles them to preference when seeking federal funding from the executive branch. Enterprise community status has contributed to the $5.9 million yearly operating budget of the Fort Peck Community College, which has in excess of 50 federal, state, and private grants programs for the community. The community has received a total of $60 million in funding with the leveraged support of the enterprise program, says Mark Sansaver, executive director of the Assiniboine & Sioux Tribal Enterprise Community. “There are approximately 20 tribal businesses and 70 small private businesses, not including at least 100 cottage-based industries,” he says. Fort Peck Tribes also see the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial as an economic opportunity for tribal and private business partnerships. Fort Peck Tribal Executive Board Chairman Arlyn Headdress says one of those projects on the table is converting a tribal ranch on the west side of the reservation into a dude ranch for tourists. The Fort Peck Tribe, as well as the Blackfeet Tribe, is looking to tap the state’s largest untapped energy resource: wind. According to a feasibility study done last year, a 200-megawatt wind farm in northeastern Montana would create enough electricity for about 10,000 homes and good- paying jobs. The project is especially welcome as energy prices are expected to spike in the soon-to-be deregulated market.

An outside group would own the turbines to take advantage of federal and state tax incentives, but the tribe would have an ownership stake and would earn royalties off each turbine. “The wind project will create and meet low-cost energy needs on the reservation,” says Headdress. The biggest economic boom will come from the construction and operation of a rural water system on and around the Fort Peck Reservation. The legislation, signed by former President Clinton last fall, authorizes $175 million to be spent over 10 years on the development of the water system and will provide water for more than 24,000 people and livestock on and near the reservation. The Indian Health Service has several times warned Fort Peck residents that high sulfate and iron levels make the water unsafe in some communities. The high levels can aggravate diabetes and heart problems. The new water system will help bring people and more jobs to the reservation, Headdress says. Tribal officials are optimistic that those plans —and others they hope will come out of an all-reservation economic summit planned for June in Great Falls—will bring a measure of prosperity to the reservation. For now, the many residents who rely on firefighting income are grateful that when fires threaten the West’s forests, the Forest Service and the state know they can rely on Indian crews to help battle the blazes. Putting his life on the line In 1979 Harvey Campbell, like many other rookie Indian firefighters, turned to firefighting for the money. “I wasn’t working and could make some quick money, so I started firefighting,” he says. He earned about $6 an hour. He says he’s continued doing it ever since because it “was at first for the money, but after a while I started enjoying it and looked forward to going out every year.”

Over 14 days last July, Campbell worked 200 hours and made $3,000, at $15 an hour as a two-crew “strike team” leader in the Bitterroot. Firefighters start out at $10.68 an hour and, on average, make $2,000 a dispatch. Until a few years ago, crews were able to stay out a full 21 days, take a day or two break, and go out again. But now the longest duration that firefighters can stay out is 14 working days because of the exhaustion that takes a toll after weeks of working hard. Most firefighters are men, ranging from 18 to 60 years old. Nine of the 330 firefighters last season from Fort Peck are women. Women often work on camp crews, but also are employed as sawyers, emergency medical technicians, firefighters, squad bosses, crew bosses, and as finance personnel. Also, other women, and some men, take on contracts for food, kitchen, mobile showers and laundry services, which also generates a lot of money. Campbell says that other than the pay and a limit on consecutive days on fire lines, little has changed about the work. In his 22 years on crews, Campbell has walked the fire trails of Oregon, Idaho, California, New Mexico, North Dakota, and Montana and has qualified for nearly every position in the wildland firefighting ranks. After his first three fires as a firefighter, Campbell was promoted to squad boss. He’s since been a crew boss, crew representative, strike team leader, instructor, and strike team engine leader. Working hard has been Campbell’s way of life ever since he was a boy, growing up the second oldest child of 12 children. With the addition of stepbrothers and sisters the family numbered about 20. In 1995, Harvey and Monica Campbell got married. “I more or less told him marry me or forget about me, so he married me. It was the best thing I ever did,” says Monica. The Campbell children already reveal characteristics of their father’s work ethic. His 16-year-old son, Richard, helps him with his insulation business, especially when his dad is busy fighting fires. The Campbells’ son Ely was the student of the month in February and earned perfect attendance last quarter. Ely says he wants to follow his dad’s footsteps as a firefighter because it is “scary and dangerous.” When Campbell is away over the summer, Monica says, “It’s not bad, I just get lonesome.” And when he returns from a fire he carries around his portable scanner, waiting for the next fire call. “I can’t wander too far from the house,” he says.

Working six or seven days a week or being gone for two weeks at a time doesn’t give him much time for family get-togethers. So in the summer, he tries to make it to as many of his sons’ baseball games as he can. This summer he thinks he’ll spend the bulk of his time conducting “pack tests” and Standards for Survival training. Applicants who pass pack tests—a strenuous three-mile walk they must complete within 45 minutes while carrying a 45-pound pack—then take the survival course. “After they stop doing the pack tests, I might be able to go out, unless it is severe as last year, then I’ll have to stay back” at the fire hall, he says. He likes the work and the extra income firefighting gives him, Campbell says, but “being home with family and taking care of them” is when he is the happiest. |

Last

updated

9/18/04 2:57 PM

Table of Contents | About Us | Feedback | Links