|

|

||

|

Breaking tradition at Fort Belknap One tribal business

after another has gone broke. Story by Jason

Begay Three years ago Fort Belknap Grocery, the only full-service grocery store on the 650,000-acre Fort Belknap Reservation in northcentral Montana, closed its doors for a second time because it couldn’t turn a profit. Another enterprise, Fort Belknap Farm and Ranch—which, like the grocery, was owned and operated by the Assiniboine and Gros Ventre tribes’ governing body—shut down in 1999, leaving a $700,000 debt for the tribal council to pay off.

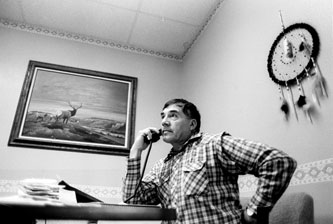

A mixture of compassion, tribal politics and a lack of business acumen have doomed assorted Fort Belknap tribal businesses and cemented a tradition that seems nearly impossible to change. Fort Belknap Indian Community Council President Joseph McConnell knows that well, because he admits he’s been part of the problem. To be exact, McConnell blames the Fort Belknap Indian Community Council, which has been the driving force behind the tribal enterprises. And as a result, the council has also been the driving force behind each tribal enterprise failure, McConnell says. “I think, if politics could have stayed away from these, the enterprises could have succeeded,” McConnell says. Within the past five years, Fort Belknap closed or ended seven of 12 tribal enterprises, including the Fort Belknap Grocery, Farm and Ranch, Utilities, Ventures, Gaming, and two separate contracts administered by Fort Belknap Industries. The most recent fatality is Fort Belknap Bi-N-Go (pronounced Buy and Go), the local gas and food station that was placed up for sale or lease by the tribe in mid-March, though it was making a profit. “The tribal enterprises seem to be moving in reverse,” says Arthur Stiffarm, Fort Belknap tribal planner. “But the private sector keeps growing.” Stiffarm refers to privately owned and run businesses that have sprung up throughout the reservation in the past five years. Increasingly, individuals are producing and selling everything from gift baskets to star quilts, offering services like a mobile shower at powwows or a taxi ride in a pickup truck across the sparsely populated reservation. However, these entrepreneurs face the same problems in their small businesses that the tribe faces within its own. With 5,281 residents, the reservation has one of the highest unemployment rates in the state at 69.89 percent. And this rate doesn’t include the 262 tribal members with jobs whose income falls below the poverty line as established by the Department of Health and Human Services.

According to its guidelines, a family of four making less than $17,650 is considered poverty stricken. Any business would find it hard to survive in an economy with a foundation like this. Forty-two businesses exist on the reservation, most privately owned and operated. But economic depression is only the beginning. Another factor plays an ever-present role in hindering business development and McConnell knows from painful experience how big a role it plays. McConnell, whose term as chairman ends in November, is the first to admit that tribal politics shouldn’t mix with business. It’s a lesson, he says, that the tribe has learned the hard way—with a $700,000 bite in the tribal general fund. Fort Belknap Enterprises are businesses designed by the tribal government to economically benefit the tribe. Some of the businesses, like the Fort Belknap Kwik Stop, now called Bi-N-Go, are meant to serve reservation residents with necessities like food and gas. Others, like Fort Belknap Bingo, are open to make money, and at the very least, to provide some form of entertainment for the older generation at Fort Belknap. After 10 years, Quick Stop and Bingo are two of the five tribal enterprises that haven’t been mismanaged into extinction. Ideally, the tribal enterprises should be one success story after another. By now, they should all be self-supporting like Bingo, which, after 10 years, is by far the tribe’s most profitable endeavor. Unfortunately, most of the businesses ended up with a fate similar to Fort Belknap Farm and Ranch, which, after 10 years, was mismanaged into a debt that at its peak hit $700,000, which the tribe has slowly paid off with money that otherwise could have been used for tribal programs. McConnell, who has served on the Fort Belknap tribal council in some capacity off and on for a span of 20 years, has played a role in the creation of many of the tribal enterprises. He has also, in the same capacity, played a role in their downfall as well, he says. Fort Belknap Enterprises is operated by a board of directors that consists mostly of tribal council members. They run each enterprise, make business decisions, management selection, and draft company policy.

In 1989, the tribe started Fort Belknap Farm and Ranch, a business that cultivated livestock and farm produce for industrial sale. About 13,000 acres were subsidized for tribal use. Operating costs were originally kept at a minimum, just enough to purchase farm equipment and employ two to six ranch hands, depending on the season. “For all intents and purposes,” McConnell theorizes, “that thing should have really flourished.” But the farm and ranch changed management with each newly elected council, meaning the business had a board of directors with a revolving membership that changed every two to four years. And few, if any, of the members had any experience in business management. “(Farm and Ranch) seemed to grow when there was less council involvement,” McConnell says. Eventually, he says, employees were hired based not on experience or know-how, but rather on kinship or camaraderie with council members. “It’s an old tradition that’s slowly dying,” he explains. “Traditionally, tribal governments were run by large families. Families would look out for each other.” It’s a tradition that dies hard. With unemployment so high, many people would still like to see jobs go to family or friends, rather than to strangers, no matter how experienced. That’s what eventually led to the fall of Fort Belknap Farm and Ranch and the massive debt that is now almost cleared, McConnell explains. “Maybe they were hiring people who didn’t know how to run the equipment properly,” McConnell theorizes. “The equipment is expensive. If someone who doesn’t know how to use it tore up some of the equipment, it costs.” Throughout the years, the Farm and Ranch showed few signs of growth. In fact, the council was dipping into the tribe’s general fund to pay for livestock and equipment upkeep. “By all means, that should have succeeded,” he acknowledges. “There were no leases. The operation was totally subsidized. There were no taxes. The equipment was paid for. There really was no other reason, just that tribal government was trying to operate a business and failed. It’s a hard lesson to learn.” Looking back the two years since it folded, McConnell has strong theories about the fall of Farm and Ranch. “There should have been a separate board from the council set up,” he says. “But it’s that old mentality that they (the council) have to have control with everything.” He nodded an understanding, “You know how it is.”

Especially when it comes to tribal funds, McConnell says, the council feels as if it has to have a say in every fiscal matter. Even when problems are identified, McConnell says the “old mentality” has proven too big a barrier. In the mid-1990s, each enterprise was designated a board of directors which was supposed to have little involvement with the council, McConnell says. However, as new council members were elected, the council started to override decisions of the various boards. Many of the managers of these enterprises threw their hands up in frustration, he says. “A lot of times, new council members don’t want to pick up where the old one left off,” he says. “They want to create new ideas, new businesses.” When the tribes usher in a new tribal council all the existing rules can be thrown out the window. As the single lawmaking body on Fort Belknap, one administration has the power to rescind any and all the actions imposed by its predecessors. Faced with this dilemma, McConnell today cannot think of a solution to the tribal enterprise situation. Kinship on a reservation is a tie that binds tightly. Not only have tribal enterprises suffered due to mixing friend and family obligations with business affairs, so also do private businesses suffer the same problems on Fort Belknap. Janice Hawley is waging her fledgling business, White Clay Embroidery, on one event and she intends to dedicate her every spare moment preparing for it. The 58-year-old grandmother, who lives in her secluded house 20 miles from Fort Belknap Agency, is relying on the 2002 Olympic Winter Games in Salt Lake City, 700 miles from her home, to help her turn a profit. “I can’t run a business the way I should, here,” Hawley says. “I have to move to a larger clientele if I am going to survive.” White Clay Embroidery is not as prosperous as Hawley had hoped it would be, operating on her own reservation. Since she started in 1997, her $38,000 embroidery machine has not come anywhere near paying for itself. In fact, in February Hawley had to get a full-time job as claims manager at Fort Belknap Insurance to support her family, her ranch and her business. After 22 years serving the Fort Belknap tribal council in various capacities, Hawley says she grew tired of the tribes’ political scene. Basically, she says, red tape and favoritism turned her off. “As far as I’m concerned, they’re not here for the betterment of the people,” she says in a voice that reveals feelings of both frustration and bemusement. “I just didn’t want to have anything to do with politics anymore. So I decided to work for myself.” And she has been trying. After a year of research, in 1997 Hawley purchased the embroidery machine with the help of a $50,000 loan from the tribe’s Small Business Center. The initial outlay for the contraption that stands over 4 feet high in the corner of her living room was $38,000. “That’s not including inventory,” Hawley is quick to point out. However, that high price, which means a monthly loan repayment of $536, has almost crippled Hawley’s home budget. But where the council has the option of digging deeper into the tribal general fund to pull out a flailing enterprise, Hawley had to get a second job and sell off 20 head from her cattle herd. “The machine and the truck,” Hawley says of her 1997 Dodge pickup, which represents another $580 monthly payment. “The only way I could keep them is if I got a job.” The embroidery work keeps her busy after long days in the office, but doesn’t begin to make a reasonable return on her investment. During an evening in March, Hawley explains that the piece she is working on, a maroon jacket that will be embroidered with “Wildcats” and a wrestling graphic is the last of a three-piece order. She has yet to be paid for the first two pieces, “which is probably why I’m dragging my feet with this one,” Hawley explains as she sets up her embroidery machine.

It’s not uncommon for payments to come late. It’s not even uncommon for payments to come in the form of barter – a corral mending for a jacket. Hawley talks about this as if she expects late payments and occasional bounced checks. But she shouldn’t expect it, she says. “It takes the joy out of sewing when that happens,” she says with resignation. The embroidery machine, state-of-the-art when she purchased it in 1997, thunders uproariously with a 39,612-stitch design. When finished, the gold, silver and royal hues of the polyester thread will crisscross to create a shiny image of two wrestlers in their sport. At Hawley’s rate of $1 per 1,000 stitches, this is almost a $40 design. The jacket, custom ordered and with the manufacturer’s labels still hanging off the zippers, cost Hawley $22. “What I should do is double the price of the jacket. That’s what they say. When you get wholesale, always double the price,” Hawley says as she sets up the jacket for a run through her machine. “But I wouldn’t sell anything.” Instead, she will charge $65 for the jacket, giving White Clay Embroidery a $3 profit for a jacket she labored over for an hour. This is why Hawley can’t run her business successfully on her reservation. “One person told me that I have to stop running my business like a Native,” Hawley says. “And that’s true. We do that all the time. I charge less because I feel sorry. I do that all the time. “When you’re a business person, you’re not supposed to feel like that. But I do.” Not that she doesn’t appreciate her local customers. “I’m always thankful for any amount I sell,” she says. “It’s when I don’t sell anything that I feel bad.” But that’s not going to happen in February 2002; Hawley is sure of that. As her machine starts to stitch the design on the jacket, Hawley outlines her strategy for the Olympic Games. “I’m going to up my price in everything. I’ll be dealing with a different market altogether,” she says as she scans her computer for various new designs. She unravels yards of materiel and thinks aloud that the dark, soft, fluffy fabric with the American flag and buffalo designs will be vests. She only needs to find more of this fabric. Hawley is taking advantage of an opportunity opened by the Shoshone Bannock tribe in Idaho, the host tribe of the 2002 Winter Olympic Games. If she can afford the vendor price, which according to Chris Osborne, vice chairman for the Shoshone Bannock Official Tribal Host Committee, hasn’t yet been established, Hawley hopes to secure herself a spot in the Indian Village area at the site. Organizers estimate that 250,000 people will attend the Games during the opening and closing ceremonies. They also expect a daily average of 70,000 people. Vendors at the Olympic Games must have enough material to last at least two weeks. The hard part for Hawley is predicting what will sell, and how popular those items might be. She thumbs through a catalog of designs that are programmed into her machine for something unique to sell. “What all games do they have at the Olympics?” she asks as she searches for something similar to a torch design. “I’m leaning more towards the Stars and Stripes,” she concludes thoughtfully. “But, I’ve got to find a way to mix in the Native American image.” Perhaps, she says, a feather hanging off the torch.

With her extra job, Hawley doesn’t have as much time as she would like to plan for the 2002 Games. “I can’t stay up past 2 anymore,” she says. But, on most nights, Hawley will sew into the morning hours to make up for the time she loses at work. “They say, ‘If your machine isn’t working, you’re losing money,’ ” Hawley explains. “I’m losing money by working.”

The Fort Belknap Kwik Stop was headed for the same fate as the Farm and Ranch. It faced a deep debt after a decade of operation. This time, McConnell knows what went wrong and where. The store amassed a slew of unpaid charges. Families were permitted to run up huge accounts. That’s one mistake that the store’s manager, Rosie L.K. Main, says she will avoid at all costs. “I started from scratch,” Main says. “The store was $190,000 in the hole.” When she was appointed manager of the Kwik Stop, now called Bi-N-Go, in 1999, she says the store shelves were barren, the food wholesalers had stopped delivering because of unpaid debts and the gas storage tanks were dry for the same reason. “They should have closed the store,” Main says. “But the council won’t let it close.” One reason is humanitarian. Both Main and McConnell say the store offers reservation residents an important service. But another reason is that the tribe receives a 25-cent tax for every dollar of gas sold from the station, and that’s an important source of revenue. McConnell estimates the annual revenue from that tax at about $200,000, which is funneled back into the tribal general fund. When Main took the reins of the grocery store, she didn’t have store management experience but for 10 years had run Fort Belknap Bingo, the single self-supporting Fort Belknap tribal enterprise. “They mostly leave me alone with that one,” Main says about the tribal council, referring to the bingo hall. She points out that the council isn’t likely to ask that a bingo charge account be established for a needy family, as sometimes happens at Bi-N-Go. McConnell agrees that Main’s policy of no charge accounts is the right management decision. And he acknowledges that it was common for the council to request food vouchers or charge accounts for families in dire straits, a policy that played a part in the failure of the Fort Belknap Grocery. Now, with tribal social security programs, this practice is no longer necessary, he says, though that doesn’t stop people from asking the council for that intervention “just to see if they can.” Using her track record with the food suppliers at the bingo hall Main was able to slowly restock the Bi-N-Go shelves. And, despite constantly breaking fuel pumps, the store offers gas again. Although she won’t give specific figures, Main says the station made a noticeable profit in 2000, a first in many years. She’s proud to have created a business atmosphere at the store with little intervention from the tribe. “But the tribe owns this,” Main says firmly. “I just manage it.” Her point was driven home in mid-March when the tribal council put the store up for sale or lease, in an attempt to find new management. McConnell says he wants the store to run independent of tribal government and selling it or leasing it would accomplish that. It would help patrons understand that they can’t expect special treatment. “Just because the tribal government is involved, there’s a mentality that ‘Well, I’m a part of the tribe. I don’t have to pay for gas,’” McConnell says. “Anybody in the private sector could handle this better.” Even under independent ownership gas tax revenue would go to the tribe. McConnell is hopeful that the change will be a positive one. If that

proves true, it might serve as his legacy. His term expires in November

and he says he has no plans to run again for chairman. “Come hell or high water, I’m going to be there,” Hawley says. “Even if I have to sleep in my truck.” |

Last

updated

9/18/04 2:57 PM

Table of Contents | About Us | Feedback | Links