Story by Nicky Ouellet, photos by Kristin Kirkland

In the back room of the Charging Horse Casino, eight people gathered around two long tables that typically support dozens of bingo cards. Tonight though, dealt among the group were pages and pages of tribal code and the constitution of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation.

Of particular interest was in the code, the section that outlines the criminal status of possessing, selling or producing marijuana.

The eight eyed the chapter, speaking quietly over the dull buzz of fluorescent lights and air conditioning. They talked of their ailments: chronic pains, diabetes, cancer. They ticked off medications Indian Health Services had prescribed them, sometimes using both hands. In hushed tones, they spoke of the drug they believed could treat them.

A tall man, Meredith Tall Bull, entered the room.

“You’re all under arrest.”

They shrank into each other, pulling pages of the code off the table. For a second, the only sound was the hum of the lights.

Then they erupted.

“This ain’t in your jurisdiction!”

“Not without a jury!”

Laughter filled the room. The group recognized Tall Bull as one of their own. The meeting at the casino was perfectly legal, but many of them rightfully feared arrest. They had met to research tribal, state and federal laws regarding legalizing medical marijuana.

Under tribal sovereignty, tribes can enact laws separately from the state that surrounds them, answering only to federal jurisdiction. This is why even though Montana has a medical marijuana program, possession or use of cannabis remains a criminal offense within the boundaries of the reservation. But a recent move by the U.S. Department of Justice could change that.

In December 2014 the DOJ announced it would not enforce marijuana laws on Native American reservations. In fact, in what is referred to as the “Cole Memorandum,” the DOJ gave guidelines for tribes choosing to legalize marijuana for recreational or medicinal use. The memo relinquished jurisdiction of marijuana laws to tribal governments.

For the group at the casino, the memo represents hope for improving their lives on the reservation. Known as the Green Side, they have been working since the beginning of this year to educate tribal members about the health and economic benefits of medical marijuana. They want to create a cannabis industry on the Northern Cheyenne reservation.

Others share this goal, and are racing along a parallel track toward legalization of a drug that could treat the myriad ailments that plague the Northern Cheyenne. But they fight an uphill battle. A long history of addiction and reluctance to pioneer legalization of a controversial substance hold just as many back.

A solid man in a black t-shirt quietly but firmly led the Green Side discussion. Waylon Rogers founded the group in January as a social media campaign to educate tribal members about the potential health and economic benefits of legalizing marijuana. What began as a closed Facebook group to find supporters and possible business partners is now an open forum for discussion, with 287 page followers and a dozen insiders who regularly attend Rogers’ meetings.

In an attempt to sway public opinion, Rogers writes daily posts on the page to answer questions and link followers to articles and studies.

“It’s the 1970s way of thinking of marijuana, the reefer madness,” Rogers said of the resistance he’s encountered to legalization. “I see why they think that way because that’s how they grew up. They were scared of the marijuana plant.”

Rogers has held several information sessions, including one with delegates from the Northern Cheyenne Tribal Council in February, to explore avenues to legalization.

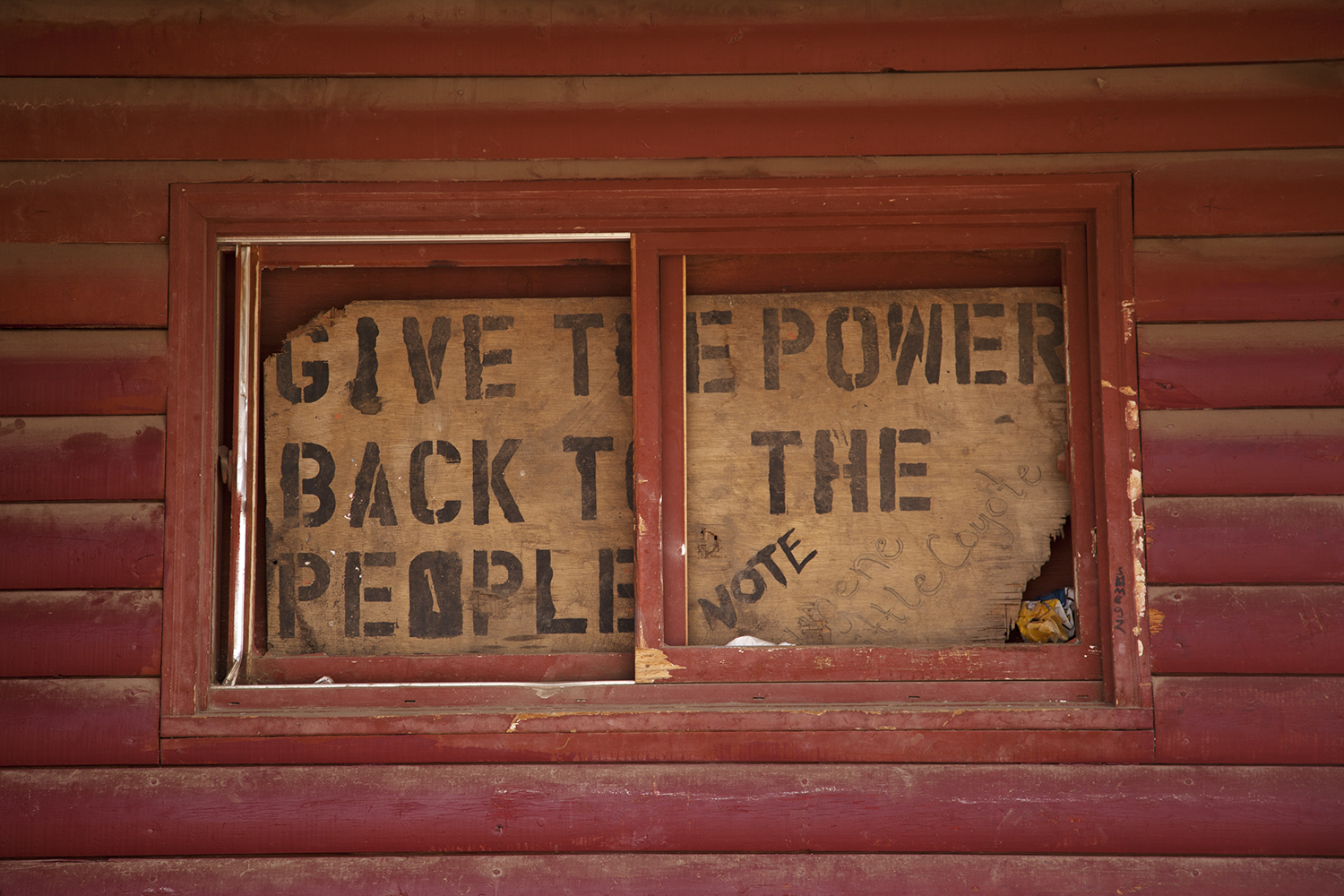

Enlarge

The purpose of this Green Side meeting was to draft language for a reservation-wide referendum vote to legalize production, sale and possession of medical marijuana. This was how Montana initially legalized its program in 2004.

Among late-comers to the meeting was Carrie Braine, a confident, spiky-haired middle-aged woman. She leafed through the tribal code and intently read over Roger’s agenda for the meeting, which included setting dates for district meetings, a timeline for the vote and a review of the proposed business model.

As voices rose in excitement, Braine’s surfaced to the top, telling the group about her cousin, Teri Brien, and her ready-made draft legislation waiting to be considered and adopted.

At the mention of Brien, Rogers tensed, his eyes transfixed on Braine. Rogers had collaborated briefly with Brien, but distanced himself after seeing her draft legislation.

The reason to initiate a cannabis industry, in Rogers’ mind, is to benefit everyone on the reservation. Rogers feared Brien would write regulations in a way that would allow her to select producers and distributors. He saw it as a back-alley attempt to monopolize marijuana.

Brien is also hesitant to collaborate. In early meetings, she said Rogers seemed eager to explore all uses of cannabis, including recreational. She feared this could weaken public support of any marijuana program and distanced herself from Rogers to improve the chances of legalizing a strictly medical program.

But, even legalizing medical use is too much for some on the reservation.

Joey Littlebird, Methamphetamine and Suicide Prevention Initiative Program Director, likened legalizing any form of marijuana to opening the door for looser regulation of other substances prohibited by the tribe, like alcohol.

“Once meth came here, it’s here to stay. Just like alcohol, marijuana, it’s here. We’re never going to get rid of it,” he said.

The “Cole Memo” did not change existing laws regarding marijuana. It remains one of the most highly regulated substances nationwide, categorized by the Drug Enforcement Agency in the same category as heroin, peyote, meth, and ecstasy.

To change enforcement on the reservation would require either a referendum vote by the people, or a vote by tribal council. Brien presented her own draft legislation to amend tribal code and regulations one week before Rogers met with the tribal council to discuss a referendum.

The council wouldn’t comment, saying only that they are aware of the issue and working to educate themselves about the pros and cons of medical marijuana legalization.

A referendum vote has two stages: the petition and the vote. Rogers needs to collect signatures from 10 percent within each of the reservation’s five districts, roughly 670 names. The actual vote needs 30 percent approval, about 2,000 ‘yes’ votes, to pass. The last election in 2014 had less than a quarter of the eligible voting population turn out to vote, which was described as pretty good, by a tribal secretary. But the total number of voters was less than the minimum required to pass Rogers’ referendum.

Rogers is undaunted. The possibilities for successful business ventures and a healthy tribe are too alluring. In its final form, the Green Side will become a co-op style production facility where tribal members could trade hours for medicine. Run by and for tribal members, the Green Side would function independently of tribal government.

Rogers only recently converted to green medicine. After an accident at work left him with a broken back and surgery left him with chronic pain, he gladly accepted a prescription from IHS for hydrocodone. But when he returned for a refill after two months, the agency refused and labeled him a pill seeker, a common accusation on the reservation that hints at its history of substance abuse.

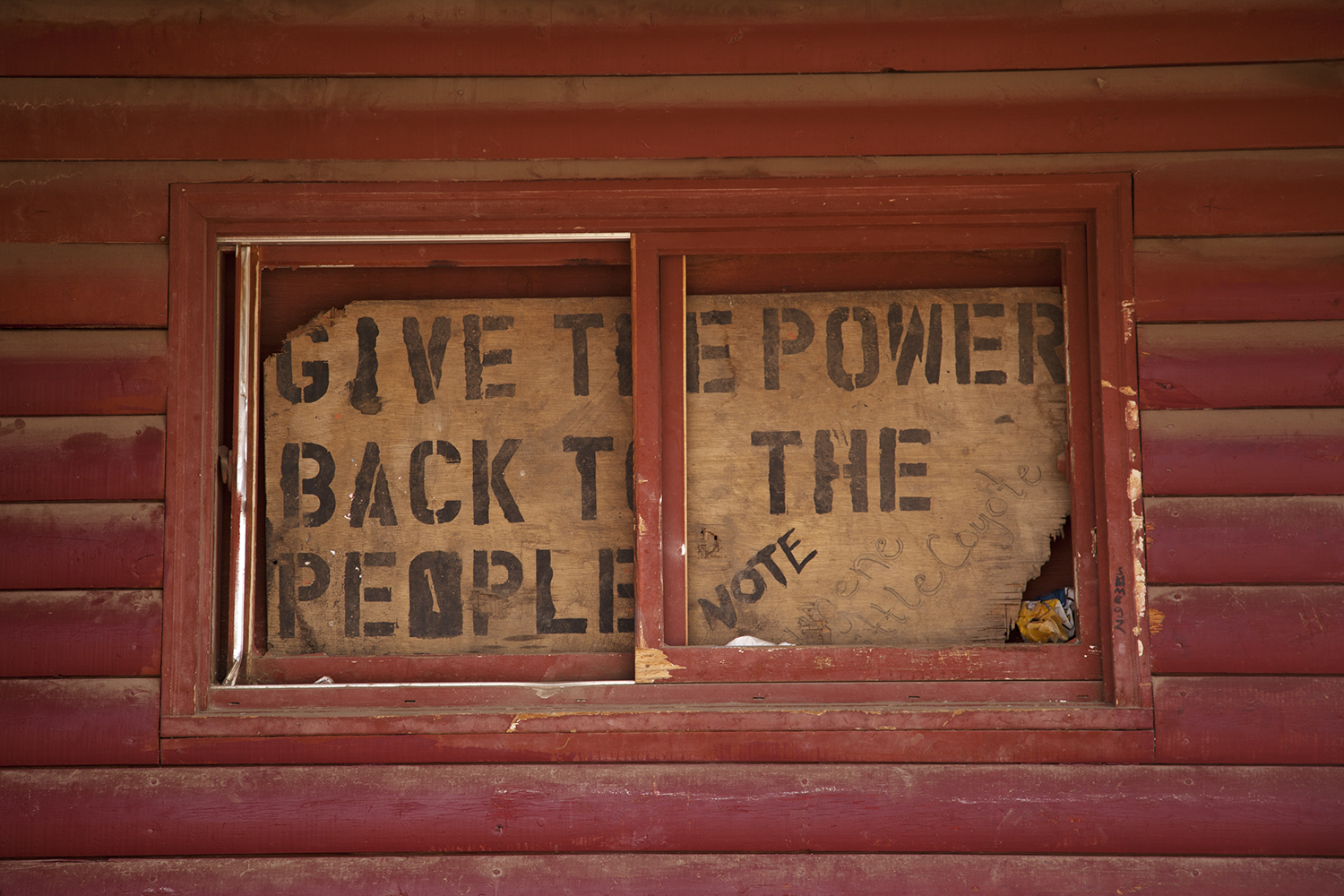

Enlarge

Brien and Rogers are paving parallel inroads to legalization. They likely will not join forces, though they each recognize the work of one could benefit the work of the other. Mutual fear and suspicion of each other keep them on their separate tracks.

They do agree that this future industry should stay in the hands of the people. They see the potential for economic growth, safer streets and an energized citizenry. They see a brighter future for the reservation. They see a return to normalcy.

For Brien, this means being able to go home to the reservation, a place she has felt banished from since she got her Montana state-issued medical marijuana card and began taking cannabis oils.

“I’m just asking the tribal council to please recognize card holders so we can be able to come home without fear of being arrested,” she said at home in Billings. “I’m a landowner down there. And I can’t live on my land and take my medicine.”

Brien was diagnosed with stage IV colorectal cancer in 2009. Sitting on the cold hospital bed, she listened as her doctor told her to make her final arrangements: The cancer was so advanced there was nothing to be done. She would likely die within eight months.

She started chemotherapy after a second opinion. She watched her body shrink as it was subjected to rounds of radiation that made everything taste like metal. She underwent surgery to remove a third of her liver after tumors bloomed there, and after it grew back with more cancerous tissue, another surgery to remove it again.

At times, she considered her body more machine than organism. Tubes funneled chemotherapy agents into ports above her heart and at her waist, sapping her hunger as it shrank the metastasizing masses. Malnourishment seemed just as likely to kill her as the cancer itself.

And then her husband suggested she smoke marijuana to regain her appetite.

It is not an uncommon suggestion. Extracted compounds from the cannabis plant have been used in prescription medications since the 1980s. The two best-known compounds, THC and cannabidiol (CBD), have been linked to treating vomiting and nausea caused by cancer chemotherapy treatments.

Some studies go even further, claiming cannabis compounds treat an array of chronic ailments — cancer, diabetes, ulcers, arthritis, migraines, insomnia, depression.

Marijuana regulations make clinical trials difficult, but burgeoning interest from pharmaceutical companies has brought money to fund research.

Sean D. McAllister studies the effects of cannabis compounds, particularly CBD and THC, on breast and brain tumors as a research scientist at the California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute. Model data suggest that CBD effectively targets the gene that scientists have linked to controlling cancerous cell growth.

By blocking this one gene, the compounds not only inhibit the cancer’s spread, they also stimulate hunger in patients weakened by chemotherapies.

“It looks promising,” McAllister said of model results, but also acknowledged gaps in definitive data from clinical trials. Most support for the healthful impacts of cannabis stems from anecdotal evidence. Until more clinical trials are conducted, he recommends a measured treatment approach.

“Based on preclinical data, the best idea would be to take [cannabis oils] along with standard care,” he said. “I’m definitely not telling people to opt out.”

Hopeful for this effect, Brien applied for a medical marijuana green card in 2010 and began testing doses of CBD oil, a dark brown, viscous liquid that tastes like cinnamon and frankincense with the faintest hint of mildewed hemp. Applied as a drop under the tongue from a ruled syringe, the oil left her head clear and tongue numb. Her hunger returned, and with it, a renewed grip on life.

But it came at a high price: She cannot take her medicine on the reservation.

Many with the Green Side share Brien’s sense of exclusion from their homeland.

One woman brandished the results of a failed urine test. THC registered positive but in such a small amount as to be unquantifiable. Still, the ambient levels could jeopardize her ability to fill prescriptions on the reservation through IHS.

BRANDYN LIMBERHAND smoked marijuana recreationally before a car accident left him paralyzed from the waste down, but the high took him to dark places after he returned home from the hospital. He threw out his stash and didn’t think to try cannabis as a medical option until he stumbled upon a long-forgotten vaporizer pen, similar to an e-cigarette but with a hit of THC instead of nicotine. Out of habit, he took a hit.

The trace amount of pot in the pen soothed his aches in a way hydrocodone never had.

Enlarge

He started smoking regularly to cut back on prescription medications, taken in increasingly higher doses as his body built up tolerance. Limberhand plans to develop his own distributing business if a medical marijuana industry emerges on the reservation.

Others, like Melanie Charette, have similar entrepreneurial goals.

Charette joined the Green Side on behalf of her daughter, Breanna Charette, who developed an exceptionally debilitating form of epilepsy when she was seven. IHS is not equipped to handle chronic intensive care, so the Charettes moved to Billings.

Breanna Charette takes several medications to block seizures and several more to treat side effects. She’s been hospitalized by adverse reactions, lost sight in the left half of her vision and will likely develop osteoporosis by the age of 30.

Melanie Charette decided it was time to try something different and applied for Breanna Charette’s green card.

The Charettes are weighing whether to produce CBD oil for themselves or buy from a distributor. If the tribe votes to legalize medical marijuana, Melanie plans to capitalize on the natural resource.

Enlarge

But Melanie Charette is hesitant to wholeheartedly endorse Rogers’ plans. Like Brien, Charette thinks a broad push for total legalization of marijuana, including recreational, could alienate many who would otherwise support a narrowly regulated program.

To Rogers, these measures represent a means for improving life on the reservation.

Pain from the accident and subsequent surgery left Rogers jobless and scraping the bottom of his savings. It prevented him from traveling the powwow circuit, where he and his children eked out spending money running a shaved ice truck and bounce house. Home improvement projects, like repairing the deck that leans over the Tongue River at his mother’s house, remained unfinished. His right leg withered from disuse.

Rogers was reluctant to try medical marijuana for pain management. He feared his children and community would disapprove, that it would confirm the previous claims against him that he was a pill seeker.

Many elders and traditionalists on the reservation do not consider cannabis, or for that matter, peyote used in Native American Church rituals, part of Cheyenne culture. In addition to being a federally prosecutable crime, using marijuana would violate tradition and culture.

At his children’s urging, Rogers eventually applied for a green card. He now smokes one joint, low in THC, each night at his home on the state side of the Tongue River in addition to practicing traditional healing methods. He is relieved of his pain, and his children are relieved to have their dad back on the powwow circuit.

Rogers struggles to balance upholding tribal law with treating his medical condition. He saw in the “Cole Memo” a way out from both pain and poverty.

Attitudes on the reservation fall into three camps: Those who support legalization to treat medical conditions, those who fear legalization would only make the current drug scene worse and those who, before being asked by a reporter, were unaware that legalization was even a possibility.

Northern Cheyenne President Levando Fisher said this is an issue to be decided by his people.

“I didn’t want the council to make that decision. I wanted the people to make that decision by referendum vote,” Fisher said.

If they do, the tribal council would still need to amend tribal code with regulations. Brien’s efforts would simply require the council to approve by majority her ordinance to open the reservation to marijuana.

“We really firmly believe it saved her life,” Carrie Braine, the latecomer to the meeting, said. Per Cheyenne culture, the first cousins consider each other sisters. Braine has seen Brien through every step of her unexpected remission and acts as Brien’s boots on the ground in Lame Deer.

Ever the businesswoman, Brien began legally growing and distributing in 2010. By 2012 she was providing to nearly 160 clients in the Billings area. Legislation changes later forced her out of business. When the “Cole Memo” was published, she saw an opportunity to restart her business on the reservation.

Brien recognizes the Northern Cheyenne could set the stage for other tribes to take advantage of the natural resource. She drafted her ordinance with this in mind, careful to reflect the DOJ’s guidelines.

“I have every confidence that our tribe can run this program themselves, using Cheyenne people to go into business to offer the medicine to its people,” Brien said.

She proposes a measured and modest tact, basing regulations on those of states with successful programs. Her ordinance focuses on tribal council oversight, a limited number of providers and patient demonstration of true medical need.

If Brien’s measure passes, she hopes to jumpstart seeds to sell to legal growers on the reservation.

“It’s been a huge undertaking, taken a lot of energy and expense to bring this to the council,” she said. “But I believe 100 percent in my heart I’m doing the right thing.”

Caught between the hopes of healing and the fears of a potential medicine, Brien and Rogers both wait for public approval of marijuana to peak. And sometimes change comes at a glacial pace.

For past Native News editions visit the archive here.