| Summer 2004 |

Sovereignty

|

|

|

Fort Belknap Reservation A Mountain of Unanswered Questions Are health problems of reservation residents related to the mines? story by Fred

Miller

Jammi Starr Snell is lucky to be alive. She’s 14. And she considers the last 12 years of her life to be a gift from the spirits.

“She was born having seizures,” Rhonda Snell says of her daughter. Given the amount of lead that flowed through her bloodstream when she entered this world, Snell says she suspects her daughter, one of seven children, was having seizures while still in the womb. Jammi (pronounced “Jamie”) Snell, an Assiniboine, lives in Hays in the southern part of the 650,000-acre Fort Belknap Reservation. She has a condition called “cerebral atrophy.” While her body was still developing, the left side of her brain was shrinking, and it nearly caused her to die shortly after she was born. A doctor in Helena told her family she would be lucky to live two years, Rhonda Snell says. If she did, the doctor said, her mental growth would be stunted. Lead caused Jammi’s problems. Lead causes stillbirths, brain damage, and learning deficiencies. Lead can wreck the fragile bodies of tiny babies and snuff out lives before they have a chance to begin. Rhonda Snell says that before her daughter was born she had no idea lead would plague her the way it has, but there’s no doubt in her mind where the lead came from. The Snells live in the shadow of a blighted giant. Before white people confined the Assiniboine and Gros Ventre tribes — bitter enemies at the time — to the Fort Belknap Reservation in the 1880s, the Little Rocky Mountains, part of which lie only a few miles south of the Snells’ house, were sacred to the Assiniboine. The tribe gathered traditional plant medicines and held ceremonies there. But after gold was discovered in the Little Rockies in 1884 the U.S. government removed a 40,000-acre chunk of mountain from the reservation to allow non-Indians to reap the benefits of gold mining. Over the next hundred years, miners employed a popular and economical new mining method. They would pile high hundreds of tons of ore and spray it with cyanide, a highly toxic chemical, in a practice called cyanide heap-leaching. More than 100 tons of ore were needed to reclaim one ounce of gold. Cyanide separated the gold from the ore, but it left tainted hills, streams and endangered wildlife in its wake. The practice was banned in 1998 by a Montana citizens’ initiative. Could the lead that invaded her daughter’s body have come from the water that flowed from the mines? There’s no medical proof of that, no studies to confirm it. But Rhonda Snell will always believe it. Snell’s beliefs aren’t unique on the reservation. Her neighbors blame the mine sites for a litany of health problems, but little information is available to verify the connections. Snell wants the tribal government to thoroughly investigate the problems so it can better handle its sovereign responsibility to guard the health of its people. “There’s a lot of horror stories about what happened up there,” she says. Jammi Snell has little memory of her early days, but she knows what her family has told her. Before she was 2 years old, seizures were an all-too-common occurrence for her. At first, it is difficult for the shy teenager to tell these details of her life to a stranger. The Snells say they were ridiculed when Rhonda Snell and her husband, Ed, tried to persuade the family’s doctors that the mines were to blame for Jammi’s illness.

“She said that people used to make fun of them,” Jammi Snell says. While she talks, she holds a plastic baby doll, a learning tool for a junior high school class. Every now and then, the doll’s electronic voice box cries, and Snell “feeds” the doll or changes its diapers. The doll is to teach her and her classmates how to care for a baby. Holding the doll in her family’s living room, Snell resembles an odd mirror image of her mother in a video about the mines made about 13 years ago. In it, a younger Rhonda Snell cries tears of anguish and holds a wild-eyed child — Jammi. The doctors prescribed phenobarbital, Tranxene and other medications for Jammi’s seizures. They told Rhonda Snell the lead in Jammi’s system probably came from paint or plumbing in the Snells’ house, and in any case, the water at Fort Belknap was just fine. Some state authorities also say the mines did not cause Jammi Snell’s problems. Wayne Jepson, Bureau of Land Management project officer for reclamation of the mines, says high levels of lead have never been found in the reservation’s well water or the water flowing north from the mines. Cyanide does not dissolve lead, he says. He agrees that the lead probably came from a household source. “Basically it’s impossible that what they’re observing could have been related to the mines,” Jepson says. But when doctors said Jammi’s time on Earth would be limited, Rhonda Snell felt like they had pronounced a death sentence. “They told me my daughter would only live to be 2 years old, if she lived that long, and I got immediately angry and I said, ‘You’re not God. You’re not going to tell me how long my daughter’s going to live,” Snell says today. Because she felt she wasn’t getting the help she needed from the Indian Health Service and her tribal leaders, Rhonda Snell and her family found a more powerful medicine: the sun dance, a traditional ceremony of prayer and fasting to call on the spirit world to heal loved ones. “So what they did, her and her husband, they went and danced in the sun dance, two years straight,” remembers Virgil McConnell, Rhonda Snell’s father, “and that little girl came out great.” Today Jammi Snell is an ‘A’ student in the eighth grade at Hays/Lodgepole Middle School. She still has occasional seizures, in which she gets dizzy, “zones out” and loses awareness of what’s going on around her, she says, but they are more infrequent than they were when she was much younger. Some time after the sun dance, Rhonda Snell took her daughter back to the same doctor who had predicted her death. The doctor refused to believe she was seeing the same little girl as before, Snell says.

Today, silence pervades the peaks of the Little Rockies. But until a half-dozen years ago the Zortman and Landusky mines, two huge expanses of dirt patched with grass and separated by a narrow isthmus of pine trees, buzzed with activity and heavy machinery. In nearly 100 years, $25 million in gold was wrenched from the “Island Mountains,” so-called because they rise steeply from the vast, largely treeless ocean of prairie and scrub land below. But the heaviest mining didn’t begin until 1979, when Pegasus Gold Corp., an international mining conglomerate based in Canada, began its cyanide heap-leaching operations on the land. Previously, gold had mostly been mined in tunnels. Some had been processed with cyanide in the Ruby Mill to the south of the mountains in the town of Zortman, but never on the scale Pegasus went about it. In almost 20 years, the company netted about $300 million, none of which went to the tribes. But then Pegasus’ luck began to change. In 1994, the tribes and state filed suit against the company under the federal Clean Water Act. The tribes said mine pollution violated Fort Belknap’s sovereign right to quality water. A federal judge agreed, and in 1996 the company was charged $36.7 million in damages, which included $32 million for a cleanup bond, $2 million to the federal government and the state, $1 million to the Assiniboine and Gros Ventre tribes, and $1.7 million for supplemental environmental projects. In 1997, the tribes sued the Montana Department of Environmental Quality to stop the agency from granting a Pegasus request to triple the size of the mines to more than 1,200 acres. Less than a year later, however, falling gold prices forced the company to file for bankruptcy, and the lawsuit was moot.

Controversy over the mines continues today. In late January the tribes filed a new lawsuit, this time against the state Department of Environmental Quality, the federal Bureau of Land Management and Luke Ployhar, the current owner of much of the affected land. The tribes contend the agencies and Ployhar are not fulfilling their obligation to clean up the site. The health issues also were never resolved. “We don’t know what we’re facing here health-wise,” says Kenneth “Gus” Helgeson, an Assiniboine and lifelong Fort Belknap resident. Helgeson helped found Island Mountain Protectors, one of two tribal groups that filed the 1994 lawsuit and worked to shut down the mines. The State of Montana has done no formal studies to specifically study mine-related health effects. Pegasus started to fund a health study with the $1.7 million supplemental money from the 1996 settlement, but the company’s downfall put an end to it. The correlations have not all been proven, but Helgeson can tick off a laundry list of mine-related maladies he says he hears about through the “Indian grapevine.” Respiratory diseases like asthma and emphysema have exploded on the reservation in the last 25 years, especially among children, Helgeson says. He blames dust containing arsenic and selenium, byproducts from old mining operations he says the wind blows down to the communities of Hays and Lodgepole. Thyroid problems have been on the rise, he says. So has diabetes, a condition that affects American Indians 3.5 times more than the American public at large, according to national statistics released from the Indian Health Service. Rhonda Snell can name at least two other family members who she says were hurt by the mines. In the waning years of her life, Snell’s mother, Marie McConnell, showed high levels of lead in her bloodstream. “She couldn’t walk, it affected her so badly,” Snell said. Erik Snell, 17, Jammi’s older brother and one of Rhonda’s three sons, had a brush with mine chemicals that literally scarred him for life, Rhonda Snell contends. A little more than 10 years ago, Erik contracted a chemical burn on his arm while swimming and playing with some other children in King Creek, which flows north to the reservation from the mines. Once again, Snell says, the doctors said the mines were not to blame. “And the doctor told me, ‘Well, that looks like a chemical burn,’” Snell remembers. “‘He couldn’t have got that from that creek.’” The doctors then asked Erik where he got the burn, she says, but “they couldn’t convince him to say it was something else.” Virgil McConnell, 79, one of the founders of Red Thunder, the other group that filed the 1994 lawsuit, lives in a small log cabin just up the road from his daughter. He has watched the changes in the small town of Hays for nearly a lifetime. He says he has seen more instances of lead poisoning and chemical-related respiratory illnesses in children in the past 25 years than in all the years leading up to them. “That’s stuff that never happened to our people before,” McConnell says. Much of the water that flows down from the Little Rockies is unfit to drink or be exposed to, he says, and the animals show him that. He has gone for walks in the mountains many times and seen dead deer and beaver below the mines. Mine employees used to watch deer drink from the Swift Gulch and King Creek drainages north of the mines; then they would make bets of up to $100 on how long the deer would live, he says. McConnell says he remembers seeing a burial mound mine employees dug to hide the bodies of poisoned deer. Many of the miners themselves — white and Indian — died from exposure to chemicals the mines unleashed, he says. “Hell, we used to hunt in the mountains a lot,” he says. “We’d stop and take a cool drink, but after the mines came in we couldn’t do that anymore.” Kirby King, an Assiniboine, worked at the mines as a machine oiler between 1987 and 1992.

“We used to put on raincoats and walk through the cyanide sprayers to go check the equipment,” he says. His father also worked at the mines, and both men have come down with similar health problems, King says. Both have heart troubles, respiratory problems and diabetes. Because diabetes is rampant among Indians and some of his other problems could be genetic, King has encountered skepticism for blaming his problems on his former jobs but he remains firm in his belief. “I could basically directly relate my health problems with (the mines) and my father could probably tell you the same,” King says. King says he believes the mines bring sickness to people who have never worked at them. He often hears about respiratory problems and children contracting rashes from playing in some of the creeks. A sensory memory of his old job that still stands out vibrantly for King is the “burnt almond” smell of cyanide. Every once in a while, in the mornings when he walks from his house at the foothills of the Little Rockies, he can still smell it wafting down from the mountains.

When state officials are asked whether the mines have contributed to decades of public health problems, some acknowledge the possibility but all make it clear nothing’s been proven. Jan Sensibaugh, director of the Department of Environmental Quality, says she has never seen proof the mines have hurt the Indians, but “obviously, when you take all that rock out of the ground, crush it and expose it, there’s a lot more of a possibility” of harmful effects. Sensibaugh says arsenic and other toxic metals can be found naturally inside mountains, and streams sometimes carry them out. The Centers for Disease Control also notes this fact. This does not rule out the possibility that heap-leaching accelerated the process, Sensibaugh says. There’s just no way to be sure. Andy Huff, an attorney for the tribes in their latest lawsuit, says the tribes are frustrated by the lack of solid evidence of mine-related illnesses that would strengthen their case. The evidence is out there and the state, Environmental Protection Agency and Bureau of Land Management need to commission the studies to look for it, he says. “I don’t think they want to because I don’t think they want to find out about the health effects,” Huff claims. “I think it’s in their best interest to downplay the problem as much as possible.” Others say the anecdotes of mine-related illnesses should be looked at with a critical eye. State and tribal experts have found community wells in Hays and Lodgepole to be safe for drinking. Another record exists to balance the claims of Fort Belknap residents: a report completed in 1996 by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, based in Atlanta.

The tribes petitioned the agency to examine the streams and groundwater around the communities of Hays and Lodgepole. In its investigation, the agency looked for lead in the communities’ well water. Lead was found in two wells on the first test, the report said. One was in Fort Belknap Agency, but a later test showed the lead level had gone down. The other was in Hays, where a treatment device was installed and a later test showed an acceptable level. In some ways, the study said, the mine sites were more of a threat before 1996 than after. The report credited Pegasus Gold with removing about 75 percent of old mill tailings from reservation drainages after the company opened for business in 1979. Between 1979 and 1993, the report listed four leaks or “slippages” from leach pads that led to the spillage of cyanide into water draining south from the mines, safely away from the reservation. Most of the Little Rockies’ creeks flow south. In July 1993, according to the report, “a flood resulting from unusually heavy rainfall sent King Creek waters flowing over the Cumberland Dam spillways. The beaver dams located further down the King Creek drainage were washed out, releasing tailings that were previously contained by the beaver dams... The amount of tailings that moved and the ultimate resting place is not known.” That same summer, Erik Snell burned his arm swimming in King Creek. The Bureau of Land Management’s Wayne Jepson says the King Creek tailings were not acidic. Most of the tailings were cleaned up by the Environmental Protection Agency in 2000, he says. Ultimately, the report concluded, “the gold mining operations are no apparent public health hazard to the residents of Fort Belknap.” On several occasions Rhonda Snell has asked officials with the Fort Belknap tribal college to test nearby water for lead and other metals, but she says they ignored her. Today, water scientists at the Fort Belknap college say they are willing to test water for anyone who asks. They are “full of beans,” Snell answers, when told of their response. “They only do what they want to do,” Snell says, speaking of the tribal authorities. “It’s something else to live here.” Helgeson, who has known the Snells and McConnells for a long time, agrees with her. The dissatisfaction the Snells and others feel with their tribal representatives cuts to the heart of sovereignty, Helgeson says. “We’re right in our own country and they’re damaging us because they’re breaking their trust responsibility,” he says. “We elect them, so we should have the ability to tell them what we want.” Citing a gag order imposed by the tribes’ lawyers because of the pending lawsuit, the 10-member tribal council and its president, Benjamin Speakthunder, who resigned in mid-May, declined to comment on any issues dealing with the mines. However, earlier this year, he said, “The water pollution is just not getting cleaned up and we have to bring this lawsuit to protect our people and water. The area is still so contaminated that even the water treatment plants are discharging polluted water.” The gag order means other tribal agencies are only at liberty to divulge certain non-sensitive aspects of the case. What they can reveal speaks volumes about the toxins they say the mines have been squeezing from the mountains for decades. At the Fort Belknap College water quality lab, Environmental Research Coordinator Donna Young, a member of the Gros Ventre tribe, stands near large tanks and hoses while pointing out several small glass bottles filled with soil samples. The soil in some has settled to the bottom and is a rich, healthy brown color. This came from the top of Mission Peak, which was never affected by the mines because it lies far above them, she says. Other bottles holding dingy, tan-colored soil came from areas of the mines that have been under reclamation for about two years. The third set of samples are a diseased yellowish color. Those samples were taken directly from old cyanide leach pads, she says. In a science classroom where Billy Bell, an Assiniboine who also goes by the name Lefthand Thunder, teaches a water practicum class, are pictures taken in the summer of 2002 of the Swift Gulch drainage, which flows north toward the reservation. A small stretch of the creek is fine. Other parts of it are a frothy, pea-green color, which comes from algae plumes that only appear where nothing else will grow, says Bell, a 1999 graduate of the college. Other parts of the creek are a rusty red, reflecting a heavy concentration of iron. Years of mining have left Swift Gulch polluted, he says. Bell explains the effect the creek has on insects.

“There was thousands and thousands of dragonflies,” he recalls. “They touched down, and basically that was it for them.” Most died quickly, he says, but some stayed alive long enough to flop around pitifully. In the worst parts of the creek, there are no stone flies or caddis flies to indicate good water. To test the health of some parts of the water, scientists subject minnows and daphnia (water fleas) to the creek environment. In some tests last summer, the daphnia didn’t last 12 hours and the minnows lasted about a day. Swift Gulch may be the worst drainage, Bell says, but others, like Montana Gulch and Mission Creek, are also in danger. In some ways, cyanide is of the least concern to scientists. Cyanide breaks down in soil and rarely shows up in water, but some tests of Montana Gulch and Mission Creek have turned up trace amounts of cadmium and selenium that cyanide separated from ore long ago. According to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, cadmium can damage lungs, kidneys and the digestive system. Selenium is an antioxidant the body needs in small amounts, but breathing large quantities of selenium dust can lead to severe respiratory problems. Regarding the lead Rhonda Snell believes poisoned her daughter, both Bell and Young say they don’t know enough to be able to tell the truth of the matter. It’s possible the lead was from “historic” mining that took place before Pegasus came to the area. Some water sampling was done by the tribal Environmental Protection Agency in the 1990s, but the tests showed no alarming levels of lead. Bell thinks Erik Snell’s burns may have come from acid-mining runoff, but nobody can say for sure. At the tribal Environmental Protection Programs office today, though, some numbers are available to show more that is currently known about what flows through Swift Gulch. Graphs display comparative levels of minerals in milligrams per liter between 1999 and 2003. In 2003, iron levels in Swift Gulch were about 14 times what they were in 1999. Sulfate and arsenic levels were about 13 times more and 4.6 times more, respectively. Certain other minerals, like phosphorous and copper, dropped during those four years. Lead levels in Swift Gulch stayed roughly the same. One major concern of the tribal scientists is the pH level of the water. In 1999, Swift Gulch had a pH of almost 7. In 2002, the latest data available on the graph, pH had dropped to slightly more than 3. A drop in pH makes water more acidic. A pH of 7 is considered neutral. A pH of 3 is comparable to battery acid, Bell said. Dean Stiffarm, who works at the tribal Environmental Protection Programs office, says Swift Gulch’s drop in water quality after 1999 — a year after the mines shut down — is a frightening anomaly. It happened, he says, because groundwater broke through the earth at the top of the Little Rockies after mining had diverted its flow. The BLM’s Jepson says he isn’t sure why the metal levels have gone up, but he thinks it might have something to do with iron pyrite beneath the ground oxidizing and releasing iron and sulfuric acid.

When the younger children are not in school, brothers Erik and Vincent can be found playing guitar, working on old cars or playing basketball with their cousins. The kids take walks near their home through hills filled with the rotting carcasses of cows that died off in a brutal, Hi-Line winter. They stop to sit, then talk of childhood friends who have died in recent years from accidents or suicides. A vague sense of uncertainty about the future looms over them like the “Island Mountains” in the distance.

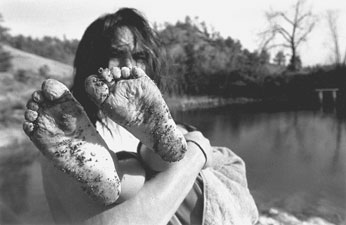

Rhonda Snell says she worries about 4-year-old Eddy — the child of a daughter who moved to Havre and the youngest member of her clan — being exposed to lead. She now guards her children fervently against the risks she says they face. She’s careful about which streams she lets Eddy play in. “When the metals come down, the bottoms of little kids’ feet act like sponges,” Snell says. She asked the Indian Health Service office to test him for lead, but they said it would be too expensive and referred her to Medicaid. It’s hard to find reliable health care close to home for her children, she explains. To get the best care, they have to drive to Billings or Helena. When treatment is needed the family sometimes supplements it with traditional medicines. When Erik Snell burned his arm, his grandfather, Virgil McConnell, used a moss that grows in the mountains to treat his skin. For her part, Jammi Snell has no doubt of the power of the spirit world in bringing her back from the darkness, but she also recognizes the role her family played in helping her to make it through the difficult times. She couldn’t have done it without them, she says. Despite all that was uncertain in her past, Snell has big dreams for her future. She wants to attend college in Ireland, then become either an interior decorator or a teacher. While her mother quietly seethes over the difficulties her family has faced in fighting its troubles over the years, Jammi Snell feels her past was a test of strength. When she was little “my mom told me that I couldn’t do anything and I always wanted to do things, but they couldn’t do them for me, and I just had to try to do them for myself,” Snell says. Family friend “Gus” Helgeson shares Snell’s independent outlook. He’s tired of waiting for others to look into possible mine connections to the health problems on his reservation. He hopes to secure grants to do an extensive study. To Helgeson, sovereignty depends on answering some long-standing questions, with or without governmental help. “They really don’t care about us so we’ve got to fight for all we’re worth,” he says. |

Last

updated

9/29/04 11:44 AM

Table of Contents | About Us | Feedback | Links